What the YouTube and Facebook statistics aren’t telling us

After the recent attack against a mosque in New Zealand, the large social media platforms published figures on their efforts to limit the spread of the video of the attack. What do those figures tell us?

Attack on their reputation

Terrorism presents a challenge for all of us – and therefore also for the dominant platforms that many people use for their digital communications. These platforms had to work hard to limit the spread of the attacker’s live stream. Even just to limit the reputational damage.

And that, of course, is why companies like Facebook and YouTube published statistics afterwards. All of that went to show that it was all very complex, but that they had done their utmost. YouTube reported that a new version of the video was uploaded every second during the first hours after the attack. Facebook said that it blocked one and a half million uploads in the first 24 hours.

Figures that are virtually meaningless

Those figures might look nice in the media but without a whole lot more detail they are not very meaningful. They don’t say much about the effectiveness with which the spread of the video was prevented, and even less about the unintended consequences of those efforts. Both platforms had very little to say about the uploads they had missed, which were therefore not removed.

In violation of their own rules

There’s more the figures do not show: How many unrelated videos have been wrongfully removed by automatic filters? Facebook says, for example: “Out of respect for the people affected by this tragedy and the concerns of local authorities, we’re also removing all edited versions of the video that do not show graphic content.” This is information that is apparently not in violation of the rules of the platform (or even the law), but that is blocked out of deference to the next of kin.

However empathetic that might be, it also shows how much our public debate depends on the whims of one commercial company. What happens to videos of journalists reporting on the events? Or to a video by a victim’s relative, who uses parts of the recording in a commemorative video of her or his own? In short, it’s very problematic for a dominant platform to make such decisions.

Blind to the context

Similar decisions are already taken today. Between 2012 and 2018, YouTube took down more than ten percent of the videos of the Syrian Archive account. The Syrian Archive is a project dedicated to curating visual documentation relating to human rights violations in Syria. The footage documented those violations as well as their terrible consequences. YouTube’s algorithms only saw “violent extremism”, and took down the videos. Apparently, the filters didn’t properly recognise the context. Publishing such a video can be intended to recruit others to armed conflict, but can just as well be documentation of that armed conflict. Everything depends on the intent of the uploader and the context in which it is placed. The automated filters have no regard for the objective, and are blind to the context.

Anything but transparent

Such automated filters usually work on the basis of a mathematical summary of a video. If the summary of an uploaded video is on a list of summaries of terrorist videos, the upload is refused. The dominant platforms work together to compile this list, but they’re all very secretive about it. Outsiders do not know which videos are on it. Of course, that starts with the definition of “terrorism”. It is often far from clear whether something falls within that definition.

The definition also differs between countries in which these platforms are active. That makes it even more difficult to use the list; platforms have little regard for national borders. If such an automatic filter were to function properly, it would still block too much in one country and too little in another.

Objecting can be too high a hurdle

As mentioned, the published figures don’t say anything about the number of videos that were wrongfully removed. Of course, that number is a lot harder to measure. Platforms could be asked to provide the number of objections to a decision to block or remove content, but those figures would say little. That’s because the procedure for such a request is often cumbersome and lengthy, and often enough, uploaders will just decide it’s not worth the effort, even if the process would eventually have let them publish their video.

One measure cannot solve this problem

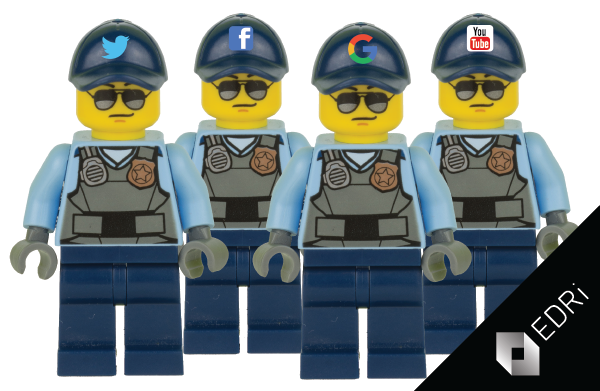

It’s unlikely that the problem could be solved with better computers or more human moderators. It just isn’t possible to service the whole world with one interface and one moderation policy. What is problematic is that we have allowed to create an online environment dominated by a small number of dominant platforms that today hold the power to decide what gets published and what doesn’t.

What the YouTube and Facebook statistics aren’t telling us (18.04.2019)

https://www.bitsoffreedom.nl/2019/04/18/what-the-youtube-and-facebook-statistics-arent-telling-us/

What the YouTube and Facebook statistics aren’t telling us (only in Dutch, 08.04.2019)

https://www.bitsoffreedom.nl/2019/04/08/wat-de-statistieken-van-youtube-en-facebook-ons-niet-vertellen/

(Contribution by Rejo Zenger, EDRi member Bits of Freedom; translation to English by two volunteers of Bits of Freedom, one of them being Joris Brakkee)