#PrivacyCamp23: Event summary

In January 2023, EDRi gathered policymakers, activists, human rights defenders, climate and social justice advocates and academics in Brussels to discuss the criticality of our digital worlds. We welcomed 200+ participants in person and enjoyed an online audience of 600+ people engaging with the event livestream videos. If you missed the event or want a reminder of what happened in a session, find the session summaries and video recordings below.

In January 2023, EDRi gathered policymakers, activists, human rights defenders, climate and social justice advocates and academics in Brussels to discuss the criticality of our digital worlds.

We welcomed 200+ participants in person and enjoyed an online audience of 600+ people engaging with the event livestream videos. If you missed the event or want a reminder of what happened in a session, find the session summaries and video recordings below.

In 2023, we came together for the 11th edition of Privacy Camp, which is jointly organised by European Digital Rights (EDRi), the Research Group on Law, Science, Technology & Society (LSTS) at Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB), the Institute for European Studies at Université Saint-Louis – Bruxelles (IEE at USL-B), and Privacy Salon.

What is the topic that brought us together?

Invoking critical times often sounds like a rhetorical trick. And yet, in 2022, we witnessed the beginning of both an energy and security crisis, caused by the Russian invasion of Ukraine. In the meantime, the world is still dealing with a major health crisis, while increasingly acknowledging the urgency of the climate and environmental crisis. In fact, crises are situations where the relations in which we are entangled change, so that understanding and making an impact on how these relations change, and in favour of whom, becomes crucial.

In this context, we asked ourselves the following questions: How do digital technologies feed into and foster the multiple crises we inhabit? What do we need to consider when approaching the digital as a critical resource that we should nurture, so as to promote and protect rights and freedoms?

Check out the summaries below to learn about the role of digital technologies in ongoing world crisis and what are the current efforts to build a people-centred, democratic society!

Contents

-

The rise of border tech, and civil society’s attempt to resist it, through the AI Act’s eyes

-

Workshop: Policing the crisis, policing as crisis: the problem(s) with Europol

-

Critical as existential: The EU’s CSA Regulation and the future of the internet

-

Workshop: Police partout, justice nulle part / Digital police everywhere, justice nowhere

-

In the eye of the storm: How sex workers navigate and adapt to real – and mythical – crises

-

Saving GDPR enforcement thanks to procedural harmonisation: Great, but how exactly?

-

Solidarity not solutionism: digital infrastructure for the planet

-

The EU can do better: How to stop mass retention of all citizen’s communication data?

-

Workshop EDPS Civil Society Summit: In spyware we trust. New tools, new problems?

Reimagining platform ecosystems

Session description | Session recording

In the context of the upcoming implementation of the Digital Services Act (DSA) and Digital Markets Act (DMA), the panel discussed their vision of a sustainable and people-orientated platform ecosystem. Ian Brown pointed out to the need for platform business innovation about interoperability. Chantal Joris expressed the vision of having more open space for healthy debate at the expense of the current monopoly of a few companies deciding on what information users can access. Jon von Tetzchner prioritised the urgency of banning current data collection and profiling practices companies are using. And Vittorio Berlota concluded that the future challenge we are set against is finding a middle ground between not over-regulating the internet and preventing companies from “conquering the world, and conquering knowledge”.

The panel spent some time to talk about interoperability, noting that it can advance the goals of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), i. e. improving data protection by empowering users to choose more privacy friendly services which in turn should create market pressure on all market participants. Concerns were expressed about the current regulatory approach giving more control to companies that rather restrict users’ speech and about companies’ ability to circumvent interoperability obligations.

The audience raised the question about law enforcement bodies and how they relate to interoperability. The speakers highlighted how a limited number of platforms would equally be beneficial for law enforcement since it would ultimately facilitate control – whereas decentralisation and the existence of a larger amount of players would make government control more difficult.

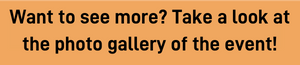

The rise of border tech, and civil society’s attempt to resist it, through the AI Act’s eyes

Session description | Session recording

The session focused on the currently negotiated Artificial Intelligence Act (AI Act) and how the legislation is failing to protect people on the move despite civil society’s recommendations. Simona De Heer highlighted the lack of clarity and transparency in the European Union’s and Member States’ development and uses of technology in migration. This technology is used to profile, analyse and track people on the move all the time. Prof Niovi Vavoula explained that these AI systems are inherently biased, creating a power imbalance and divide between foreigners and non-foreigners. While there is no ban on tech uses in migration, discriminatory practices are on the rise like emotion recognition and behaviour analysis, predictive analytics, risk profiling and remote biometric identification in migration.

Alyna Smith shed light on the impact such uses of AI-powered technologies have on undocumented people as ID checks have become part of a strategy to increase deportations. An underlying element of these practices is racial profiling and criminal suspicion against migrants. Evidence shows that 80% of border guards say that ethnicity was a useful indicator. Hope Barker highlighted that the issue is not the tech itself but the uses of tech for harmful ends. For example, reports show that Frontex officers have taken images and videos of people on the move without consent. Or cases of drones collecting a vast amount of data without people’s knowledge of how the information will be used in countries like Croatia, Greece, North Macedonia, and Romania.

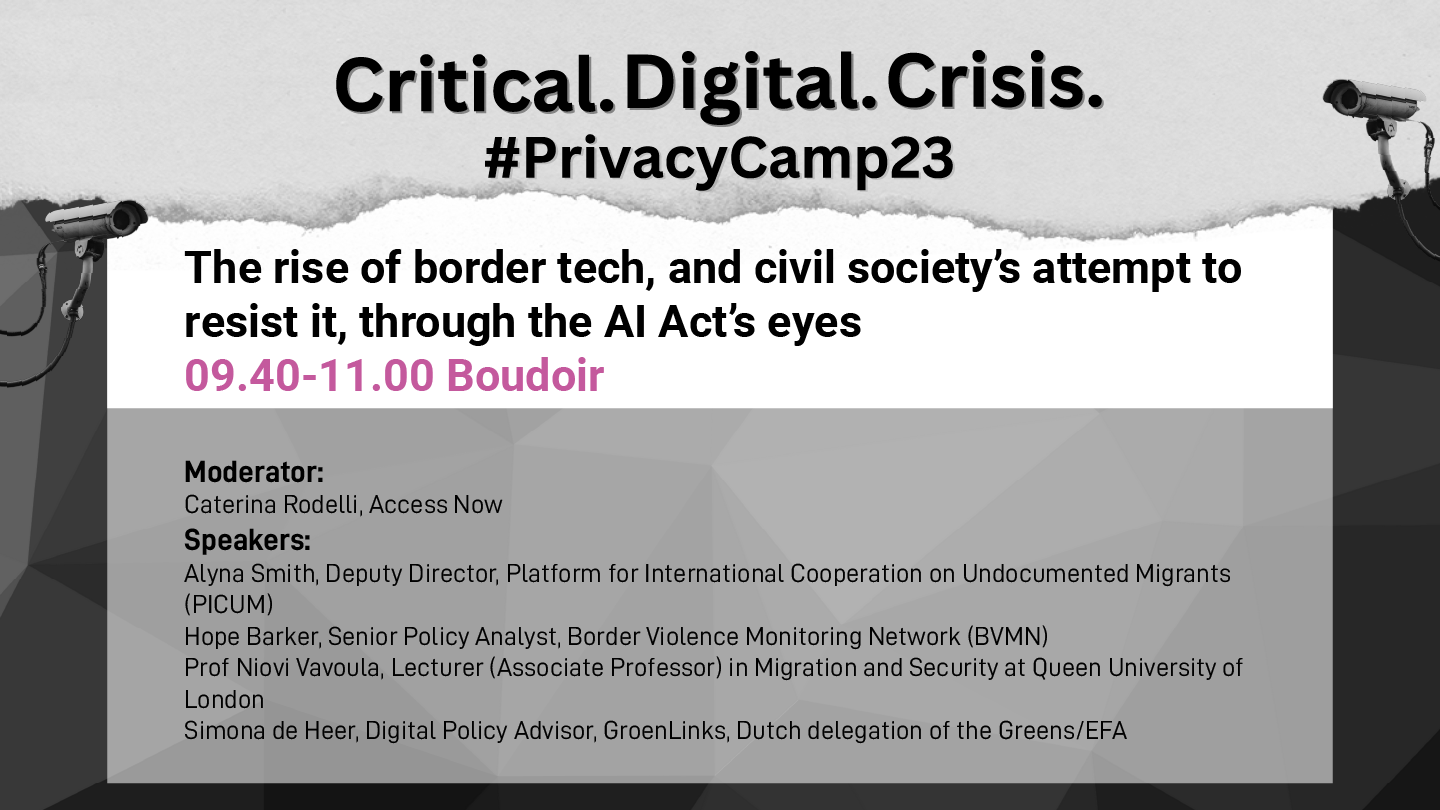

Workshop: Policing the crisis, policing as crisis: the problem(s) with Europol

The workshop engaged the audience with a series of questions about the nature and powers of Europol. Chris Jones pointed out that the last reform gave Europol many tasks that they were already executing, including processing personal data. The agency is becoming a hub to receive data from non-EU countries and may be involved in “data laundering” (using data extracted from illegal actions such as torture). Laure Baudrihaye-Gérard added that the lack of scrutiny around how Europol is processing data and unclear legal understanding if the agency can be sanctioned for misbehvaiours puts thousands of people under mass surveillance without the right to fight back.

Fanny Coudert underlined that the new reform will make it very difficult for the European Data Protection Supervisor to limit the data processing by Europol, especially in the case of large databases. Saskia Bricmont revealed that there was no strong opposition in the European Parliament or the Council during the Europol reform negotiations. Civil society’s actions had an impact on amending and ensuring some scrutiny during the reform, which, however, was rejected in the end.

Sabrina Sanchez spoke about the attempt to make “prostitution” a European crime in the VAW Directive. Since the Europol system is very opaque sex workers don’t know if they are in database where organising as sex workers is criminalised. Romain Lanneau finished with a Dutch case in which the data of a leftist activist was used by Europol. The case is the tip of the iceberg given the lack of scrutiny of Europol. Romain invited the audience to request data from Europol. See more here.

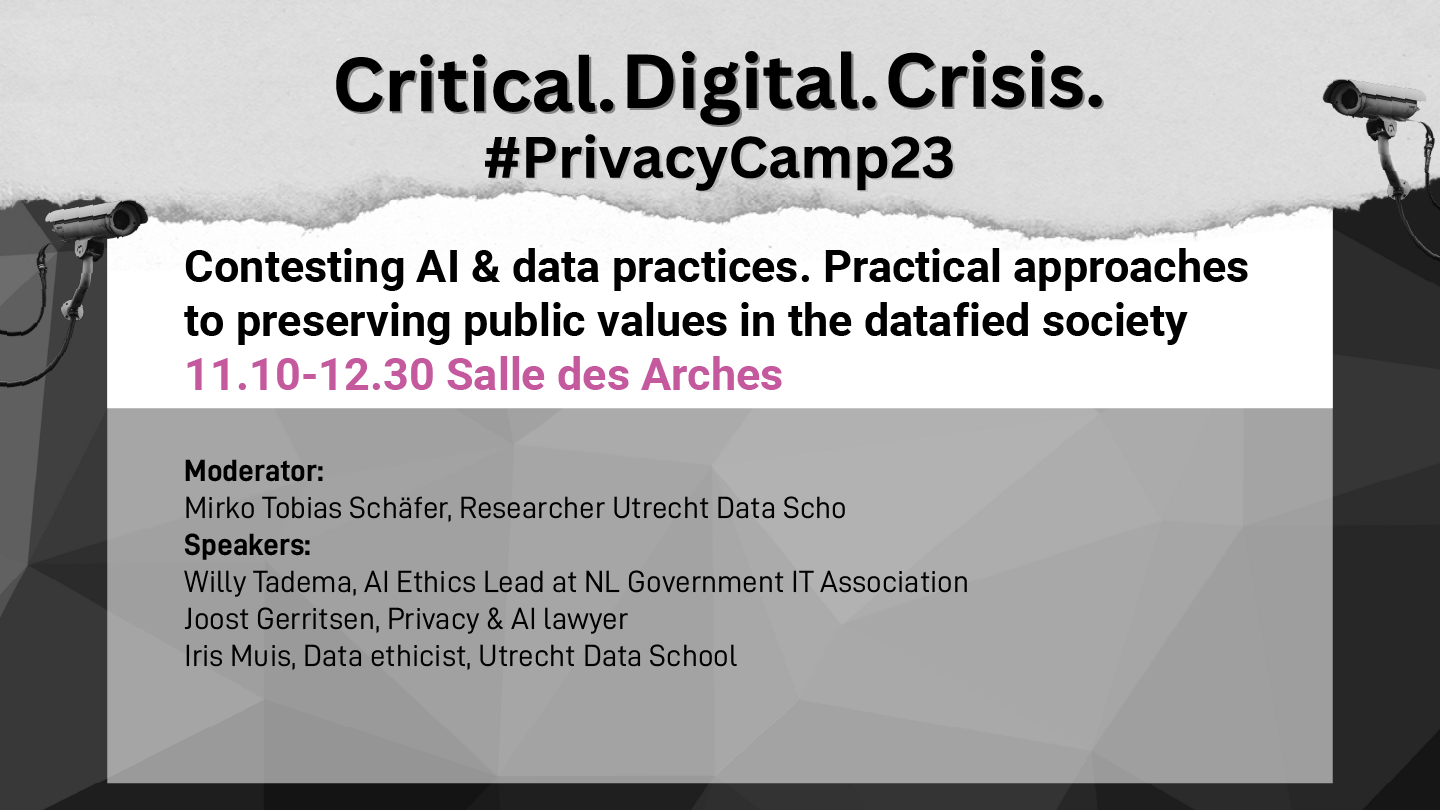

Contesting AI & data practices. Practical approaches to preserving public values in the datafied society

Session description | Session recording

The session investigated the practical implementation of data ethics from academic, business and legal perspectives. Iris Muis kicked off the conversation by presenting the tools (Fundamental rights and algorithms assessment and Data Ethics Decision Aid) Utrecht University developed and how they were used in the government sector. Joost Gerritsen made the point that implementing data practices that preserve public values should be profitable. He stressed that it’s important to acknowledge that GAFAM is not representative of the whole of Europe as there are other companies relying on artificial intelligence.

Willy Tadema took us through the recent historical development of AI and how governments relate to using the technology. Willy noted that nowadays governments are reluctant to use AI without sound reasoning. The discussion raised the question if we shouldn’t focus on the need of building an algorithmic system in the first place and then look at data ethics. The panel then followed to discuss the issue of putting the responsibility and “burden of moral decision” on the tech team. Willy pointed out that we should have all key stakeholders in the room from the very beginning, including those affected by the algorithm.

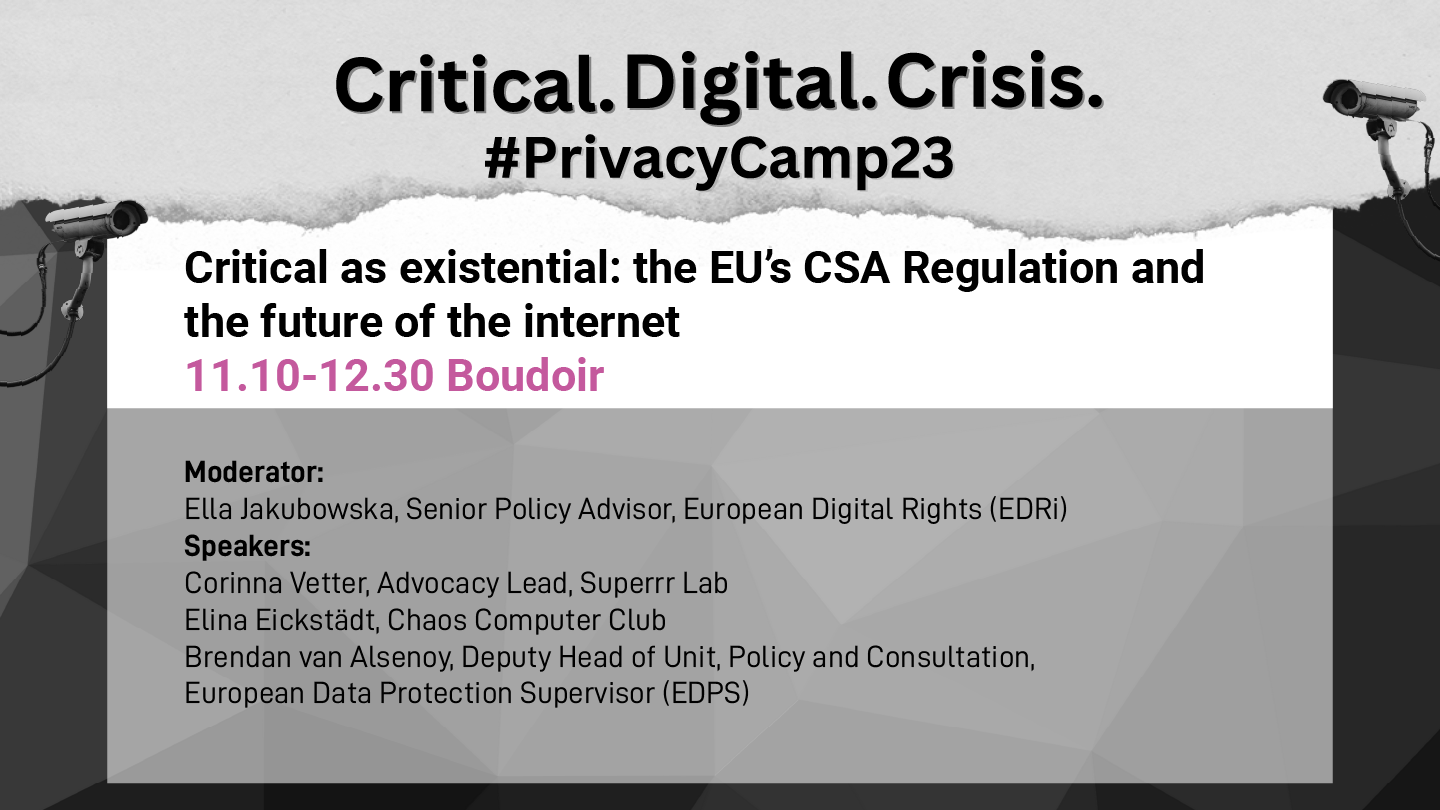

Critical as existential: The EU’s CSA Regulation and the future of the internet

Session description | Session recording

Ella Jakubowska started the panel by introducing the debate surrounding the CSA proposal which has been subject to criticism from a broad coalition of experts ranging from legal experts to computer scientists. The debate was kicked off with the participants articulating their understanding of ‘critical‘ and ‘digital‘. It would imply understanding the opportunities and limits posed by technology (Patric Breyer), they would reflect key principles of the CCC, i.e. computers can and should be used to do good, but at the same time mistrust in authority and decentralised systems were key (Elina Eickstädt), they implied that digital policy is also social policy and that we should thus be aware of existing power structures and their effects on vulnerable groups (Corinna Vetter).

Elina Eickstädt stressed that there is the belief among lawmakers that it was possible to undermine encrypted communication in a secure way would be an illusion. Encryption would be binary: either you have it, or you don’t. Screening content before it is encrypted via client-side scanning would break with the principle of end-to-end encryption, and that users are in total control of who can read their messages.

Corinna Vetter highlighted the social and labour policy issues of the CSA. Since no algorithm exists yet that could reliably detect CSA content, it would have to be done by people who would get access to private communications. Furthermore, we would already know from current content moderation practices that it is done by workers who suffer from very poor working conditions and the psychological impact of the content they have to review. Patrick Breyer presented how the CSA proposal would create a new and unprecedented form of mass surveillance.

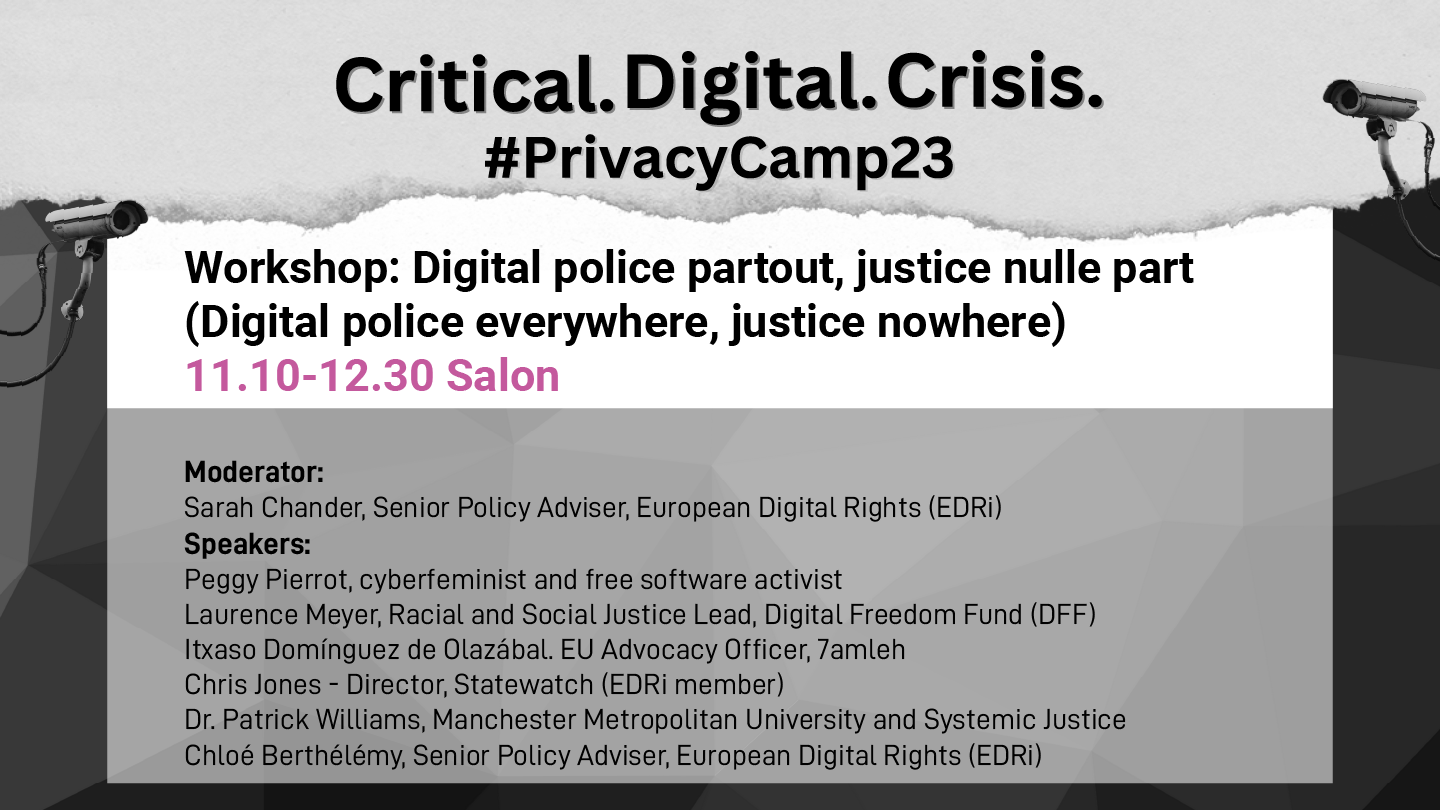

Workshop: Police partout, justice nulle part / Digital police everywhere, justice nowhere

The workshop started by focusing on trends of tech surveillance and harms to racialised communities. Dr Patrick Williams highlighted that currently the UK is facing problematic situations and crises in the police institution and what we see in this context is that institutions trying to distance themselves from the issue. Chris Jones spoke about the 2015-2016 period of people on the move coming to the European Union and the institutions’ resort to control and tracking of people as a reaction. He underlined that the problem is not the technology but power and pointed out that the materialisation of this approach on an international scale is global policing strategies.

Itxaso Domínguez de Olazábal outlined the role of Israel in the development of the techno-solutionist approach as they have built a leading surveillance industry, testing new technologies on Palestinian people. Itxaso explained that this system of extraction and testing underlines capitalist racism. Laurence Meyer explained that police and prison are not effective as there are designed to enforce order, not reduce crime or increase safety. What we have seen is that digital policing tools are both discriminatory and criminalising, impacting people who exist outside of the hegemonic structures.

The discussion concluded with a strong call to action to find cracks in the policing and criminal system and create our resistance there, to not be paralysed in the face of these seemingly perfect and infallible technological structures. We can work towards non-reformist reforms, reducing the power of the police, going beyond technology and posing a political question about abolition.

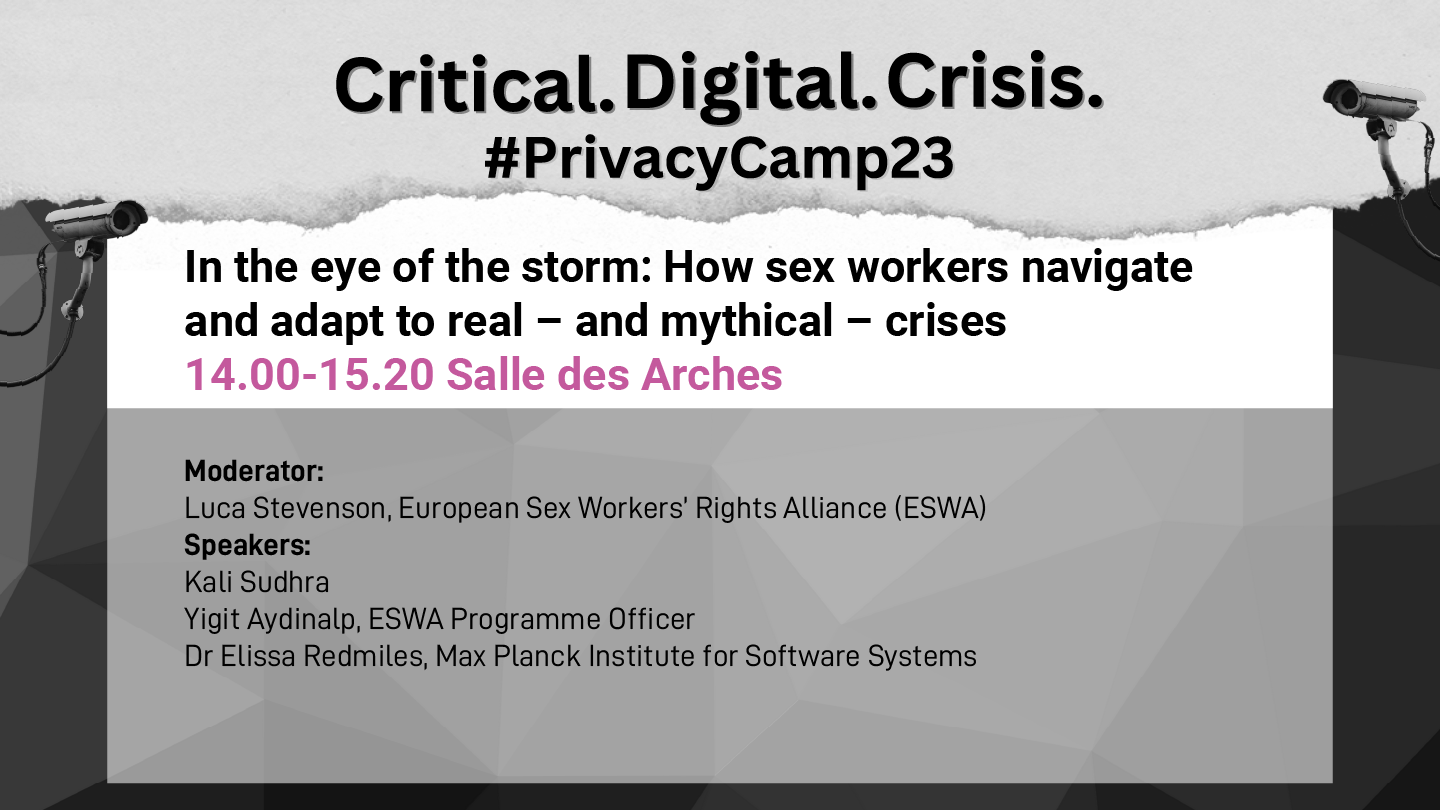

In the eye of the storm: How sex workers navigate and adapt to real – and mythical – crises

Session description| Session recording

Kali Sudhra started the conversation by outlining the context that the COVID-19 pandemic created for sex workers. Sex workers were faced with less space in their community, increased police encounters and more people moving online to do their work. However, the online environment brought more risks, including financial discrimination by platforms, as sex workers have to abide by the terms of service which are often discriminatory, require private info disclosure (e.g. PayPal). Sex workers also experience online censorship, a consequence of racist algorithms, meaning many cannot advertise services, pushing sex workers to the margins.

Yigit Aydinalp spoke about the role of private actors as enablers of harmful legal frameworks. In the Digital Services Act, the Greens introduced an amendment on non-consensual imagery, which means that hosts of content would have to collect users’ phone numbers. This violates the data minimisation principle, especially when working with marginalised communities. Sex workers were not consulted on this. In the Child Sexual Abuse Regulation proposal, we also see the over-reliance on tech solutions in response to another crisis, resulting in more surveillance to marginalised communities.

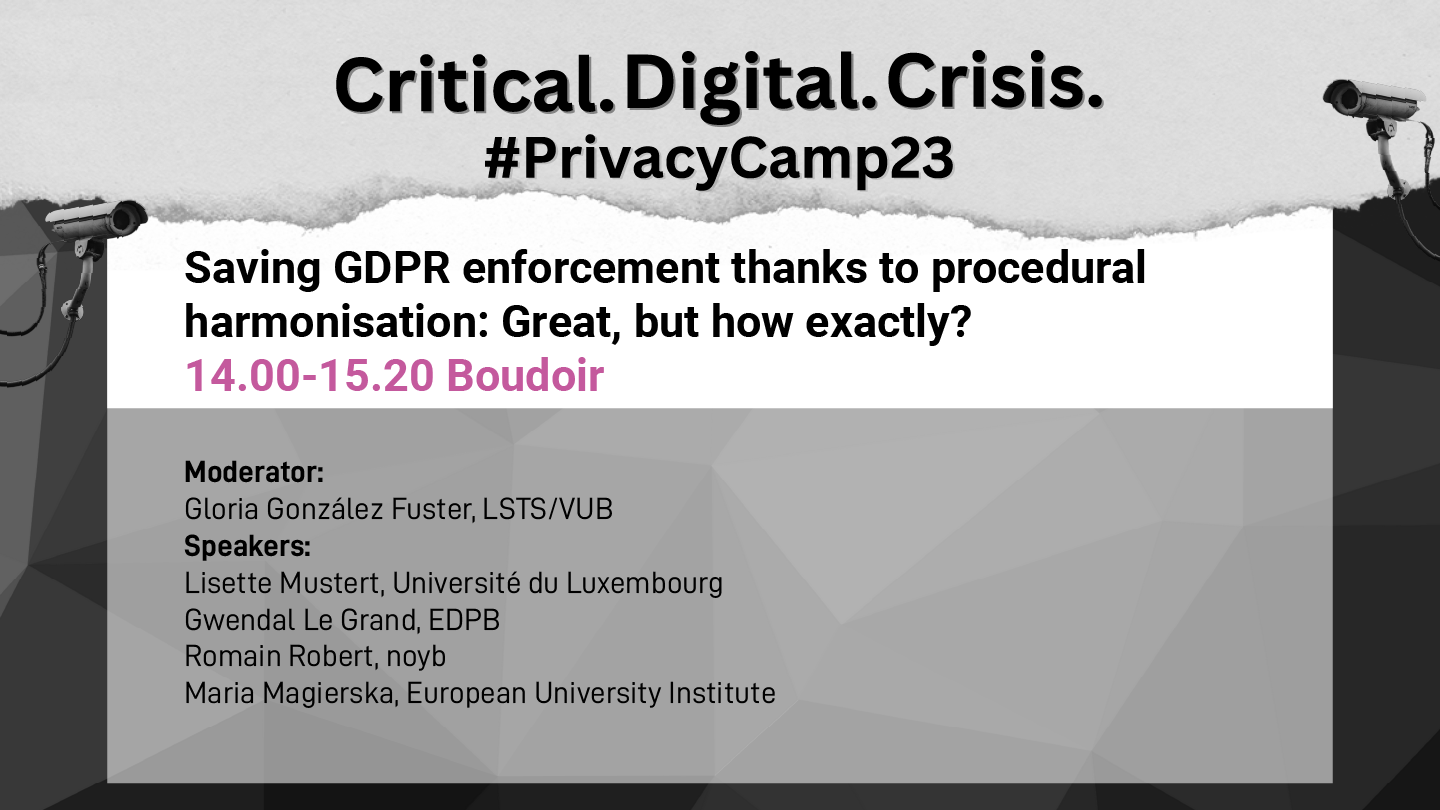

Saving GDPR enforcement thanks to procedural harmonisation: Great, but how exactly?

Session description| Session recording

Lisette Mustert focused on the cooperation between the European Data Protection Supervisor (EDPS) with national authorities to highlight how cross-border handling of data occurs and express the need for a new set of rules that will clarify the existing uncertainties. To reach a consensual outcome, lead authorities need to assist each other. The cooperation process is complex and slow and it may deprive parties of their procedural rights, which does not lead to protection of digital rights or admin rights or defence rights based on how the GDPR system is designed.

Gwendal Le Grand explained that not all authorities are always in agreement in terms of the interpretation of the law and decisions. Then we enforce dispute enforce mechanism. To that, Romain Robert gave the example of the Meta complain EDRi member noyb submitted and the many procedural issues along the way. Maria Magierska highlighted the capacity and resources limitations of Data Protection Authorities (DPAs), which should be seen as a structural problem and not an individual problem.

In their wishes of what could solve the harmonisation issue of the GDPR, the speakers mentioned the implementation of the principal of good governance, implementation of the full law, DPAs to work as fast as the EDP, make the regulation as clear as possible.

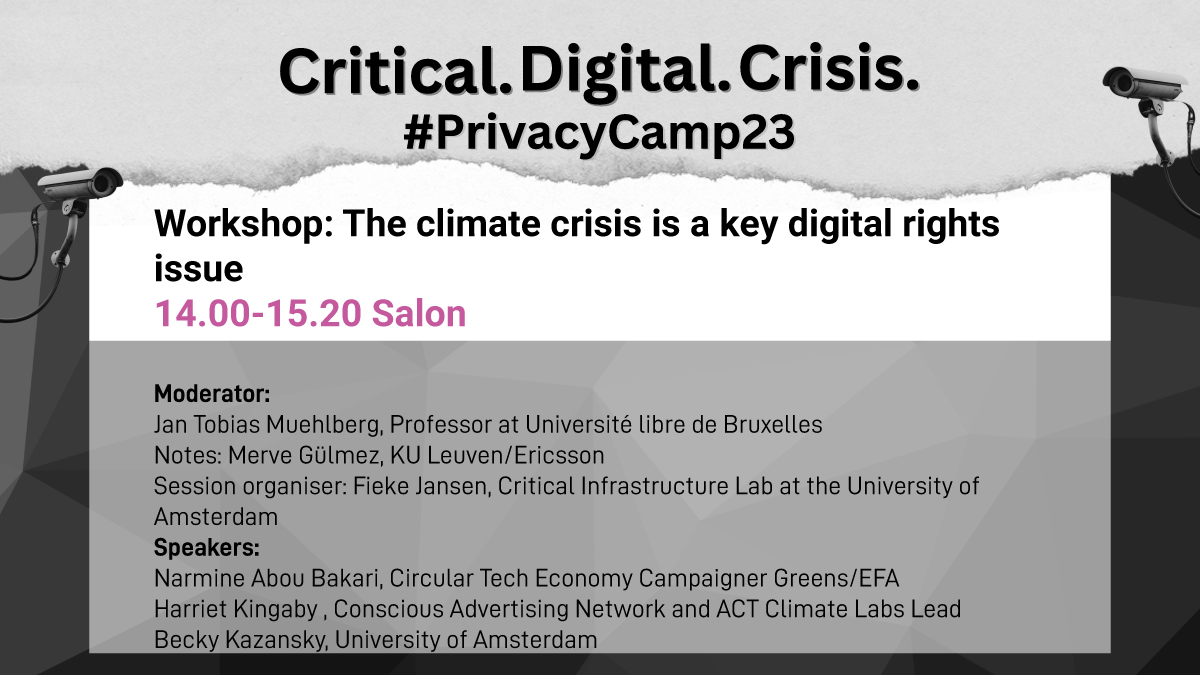

Workshop: The climate crisis is a key digital rights issue

Jan Tobias introduced the discussion outlining the question of the link between climate crisis and digital infrastructure. Harriet Kingaby focused on disinformation economy and climate disinformation, pointing out the harms advertising tools create for society. Narmine Abou Bakari presented some empirical evidence of how tech companies negatively impact the environment. For example, in 2020 tech companies consumed 9 percent of our global electricity and are right now far away from the net-zero metric. Another comparison showed that cryptocurrency mining energy consumption is equal to whole Argentina country energy consumption.

Narmine also emphasised that we need repairable devices, urging for advancing people’s right to sustain devices, choose software, transparent communication from companies and give users more control over data and software.

The speakers also discussed the questions of whose justice we are prioritising when we speak about climate crisis from digital perspective and how we can engage in these spaces.

Solidarity not solutionism: digital infrastructure for the planet

Session description| Session recording

The panel started with an overview of the historical relation between technology and the climate. Some examples link to surveillance of movements and land defenders; access to information and spreading disinformation; and extractive nature of corporate technology practices. Paz Pena focused on geopolitical ethics and the exploitation of nature by digitalisation and globalisation; and who are the communities as well as non-humans paying the price for the “solutions” to the climate crisis that have been put forward by companies.

Following that the conversation continued by revealing some of the false solutions given to climate crisis and their links to digital rights. Becky Kazansky spoke about carbon offsetting and how institutions, companies and individuals use it to compensate for their carbon footprint. Ecology is not a balance sheet, so it’s important that we treat climate pledges by tech and other companies in the same way as other digital rights issues. Lili Fuhr added that the way we define the problem dictates the solution – and what we are seeing is that tech is being brought to ‘fix’ climate and made to ‘fit’ the problem. The discussion concluded with several critical points suggesting that even though Big Tech contribute to the climate crisis, what we need to fight against is the hegemonic logic of technocapitalism as a ‘solution’ to ecological crisis. A social justice problem cannot be distilled to a feel-good practice for European consumers.

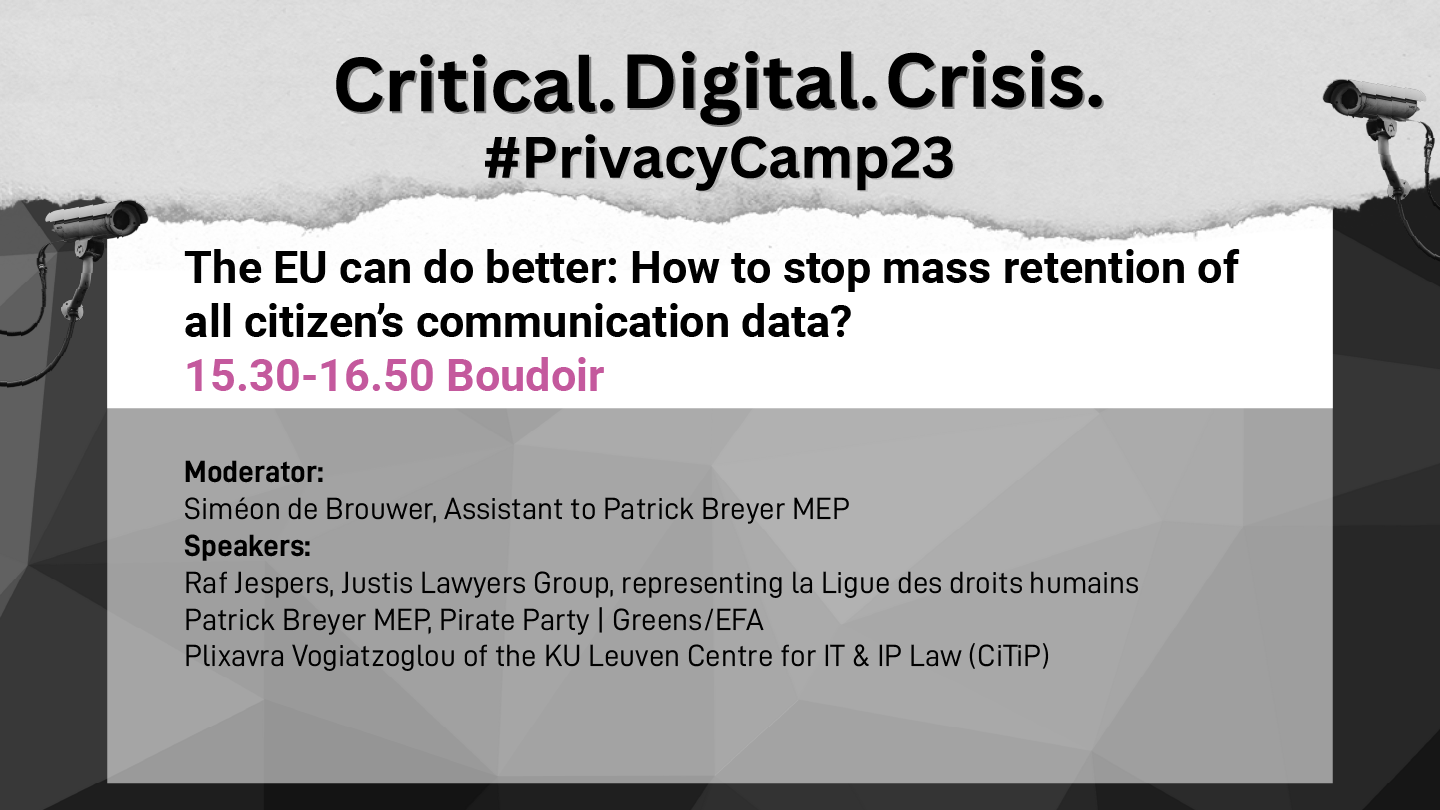

The EU can do better: How to stop mass retention of all citizen’s communication data?

Session description | Session recording

Data retention is a topic that comes and goes. Plixavra Vogiatzoglou spoke about the judicial legislation of mass data retention and some challenges that arise from it. How can we distinguish if the interference is serious or not. Data retention on itself regardless of any harms or sensitive information collection constitutes interference and conclusion is even more justified when private and sensitive information is included. Interference should be assessed as serious by the fact that this vast amount of data being collected amplifies quote significantly the power information asymmetries between the citizens and the government. Second challenge refers to the differentiation between public and national security, which seems to be made on the basis of immediate and foreseen threats. And third challenge that was presented referred to making a balance between the entering of new technology and avoiding the facilitation of mass surveillance.

In Belgium, there are currently three data retention laws, subjecting people to mass surveillance. In Germany, there is space to establish an alternative to the mass data retention approach. Furthermore, the panel discussed how the European Court of Justice reacts to the pressure coming from the Member States and what actions could be taken to defend fundamental digital rights.

Workshop EDPS Civil Society Summit: In spyware we trust. New tools, new problems?

Wojciech Wiewiórowski kicked off the discussion with a reflection on the way member states behave when matters refer to national security, recognising that many states rely on tools like spyware. He highlighted that one of the major issues is that national states security exemption is not harmonised and the different duties that Data Protection Authorities need to perform nationally. Hence, the oversight of the European Data Protection Supervisor is very important.

Rebecca White pointed out that civil society is burdened with the task of proving that untargeted mass surveillance is not the way to ensure security. Eliza Triantafillou spoke about Predator spyware investigations and the challenge of persuading the public that it is harmful to surveil journalists. For example, recent news revealed that a journalist was put under surveillance by the Dutch secret services for the last 35 years and now none of the protected sources wants to work with this journalist. Bastien Le Querrec added that other than Pegasus, there are many other uses of spyware that people are not familiar with.

The following part of the workshop took a fishbowl structure and allowed for intervention from the audience. The main issues that were raised were around national security, the efficacy of a ban on spyware, and commercial use of spyware.