EU AI Act Trilogues: Status of Fundamental Rights Recommendations

As the EU AI Act negotiations continue, a number of controversial issues remain open. At stake are vital issues including the extent to which general purpose/foundation models are regulated, but also crucially, how far does the AI Act effectively prevent harm from the use of AI for law enforcement, migration, and national security purposes.

As the EU AI Act negotiations continue, a number of controversial issues remain open. At stake are vital issues including the extent to which general purpose/foundation models are regulated, but also crucially, how far does the AI Act effectively prevent harm from the use of AI for law enforcement, migration, and national security purposes.

Civil society has long called for an EU AI Act that foregrounds fundamental rights and puts people first. This must include clear and effective protections against harmful and discriminatory surveillance. The EU AI Act must guarantee a framework of accountability and transparency for the use of AI, and empower people to enforce their rights.

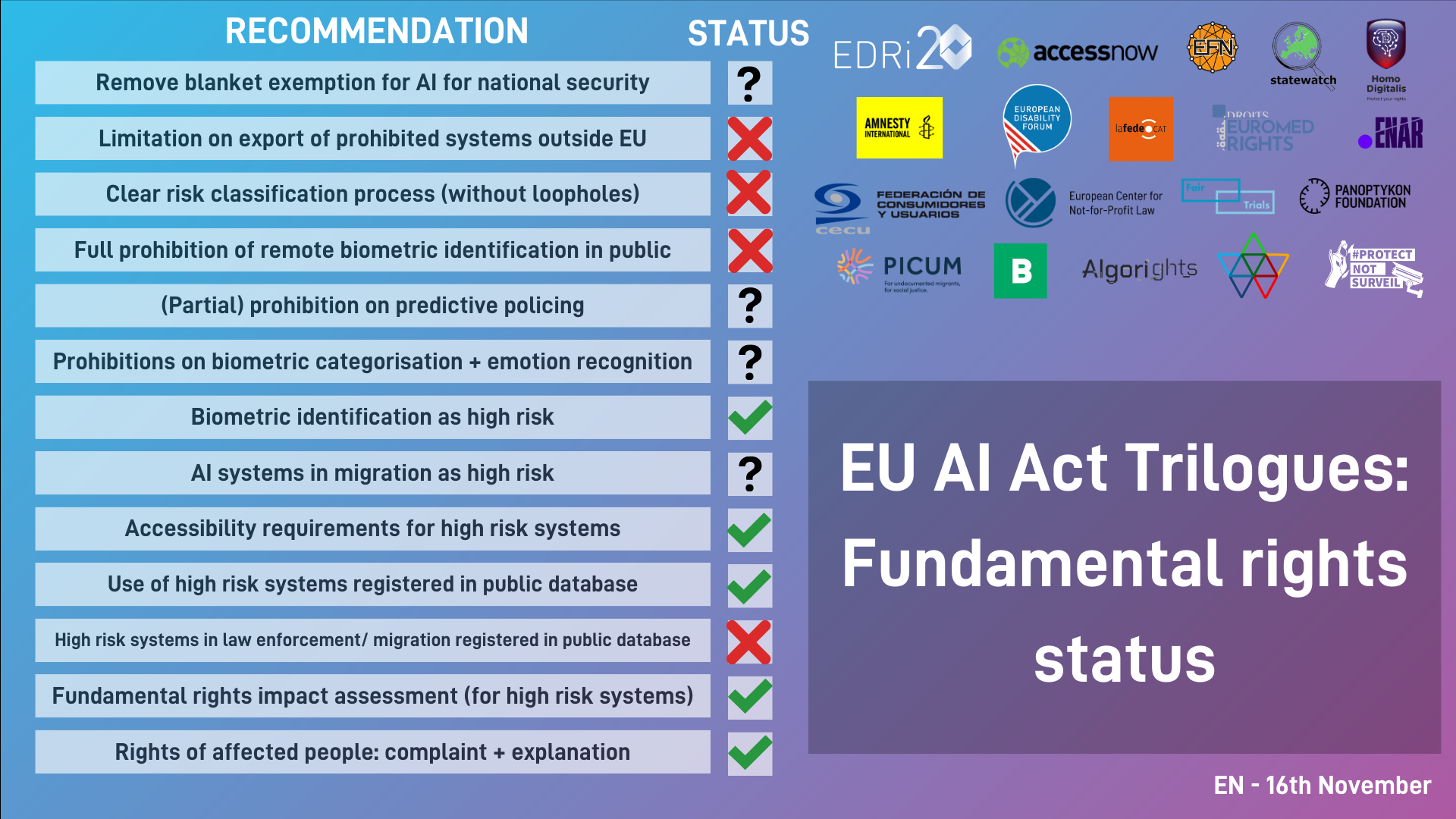

EU AI Act: Status of civil society’s recommendations

In July of this year, 150 civil society organisations called on EU negotiators to put people and their fundamental rights first in the AIAct trilogues.

This blog outlines the status of the fundamental rights recommendations in the AI Act as we understand it. However, there is still opportunity to ensure that fundamental rights are prioritised in the AI Act. Here is an update of the progress of these recommendations so far in the EU AI Act trilogues:

Remove blanket exemption for AI for national security [❔]

Civil society has called for the removal of a blanket exemption from the AI Act for all AI systems developed or used for national security purposes, proposed by the Council. The attempt to exclude from the new protections, in sweeping terms, anything to do with AI in national security, goes against established Court of Justice jurisprudence, and would make the area of national security a largely rights-free zone.

The Parliament and the Commission have proposed a compromise asserting the division of competence between the EU and Member States without going beyond EU treaties. However, media reports suggest that most governments, notably France and Germany, still block any attempts at compromise.

Negotiations are still ongoing as to whether a blanket exemption for national security will be removed from the final text.

Addressing human rights harms of EU-made AI systems outside of the EU (exports) [❌]

Overall, the AI Act has not addressed how AI systems developed by EU-based companies impact people outside the EU, despite existing evidence of human rights violations facilitated by facial recognition and other surveillance technologies developed in the EU in third countries (e.g., China, Occupied Palestinian Territories).

To address this gap, the European Parliament has proposed to prohibit the export of AI systems that are deemed to pose unacceptable risk to human rights and therefore banned in the EU. However, there is pushback from the European Commission and Council, arguing that the the AI Act is not the place to address these issues, pointing to EU law on exports, which has been criticized for being noneffective to stop export of abusive technologies and would give discretion to EU countries to allow export to AI systems despite them being banned in the EU due to their inherent incompatibility with human rights.

In addition, while the AI Act requires European and non-European companies to follow certain legal and technical safeguards if the develop high-risk systems to be used in the EU, the draft law fails to require European companies to follow the same requirements if they develop such systems for use outside of the EU.

Clear risk classification process (without loopholes) [❌]

A dangerous loophole has been introduced into Article 6 of the AI Act as a result of corporate lobbying, allowing AI developers the capacity to decide if the systems they develop are actually ‘high risk’ and therefore subject to the main requirements of the legislation.

Whilst neogiations in the trilogue have aimed to narrow this loophole in order to address these concerns, there will still be significant scope for AI developers to argue their systems are not high risk. Some safeguards will apply, including the requirement that exceptions must appear on the public database. However, significant concerns as to legal certainty and the fragmentation of the market will still apply, as well as the danger that high-risk systems will be misclassified and avoid scrutiny.

Full prohibition of remote biometric identification in publicly accessible spaces [❌]

Leaked documents from both Council and Parliament show an appetite to agree to a ban only on real-time uses, and only by law enforcement. This would be a major loss compared to the Parliament’s commitment to much broader bans. In addition, this already insufficient real-time ban would be subject to wide exceptions and limited safeguards.

Civil society groups are urging the co-legislators not to accept this outcome, which in fact amounts to a blueprint biometric mass surveillance. It would legalise a serious violation of our human rights and betray the hundreds of NGOs and hundreds of thousands of people in the EU calling for a meaningful ban.

Prohibition on predictive policing [❔]

Civil society have called for a full prohibition on predictive and profiling systems in law enforcement and criminal justice contexts, which vastly undermine fair trial rights, and the right to non-discrimination. Whilst the European Parliament included a prohibition of some forms of predictive policing in their position, the Council have pushed back, generally arguing that predictive policing systems should be merely ‘high-risk’.

Negotiations are still ongoing as to whether a prohibition of some forms of individual-focused predictive policing systems will be prohibited.

Prohibitions on biometric categorisation + emotion recognition [❔]

The European Parliament voted in June to prohibit biometric categorisation on the basis of sensitive characteristics (e.g. gender, ethnicity) and emotion recognition in workplaces, educational settings, at borders and by law enforcement. Leaked documents from the Council of Member States indicate that they are willing to express some flexibility for these bans. Options on the table include a ban on emotion recognition for education and workplace settings only – a bizarre limitation given that emotion recognition is fundamentally a violation of human dignity, equality and free expression.

Biometric identification as high risk [✅]

It is reassuring that the co-legislators seem set to list all biometric identification as high risk. This is the only legally consistent and coherent approach, as both the General Data Protection Regulation and Law Enforcement Directive rightly recognise that the use of biometric data to identify people is highly sensitive. AI systems processing these data must therefore be subject to strong controls, especially as such systems are frequently used in contexts of imbalances of power (e.g. border and migration). It is a fallacy that this would interfere with building access control, as that is not biometric identification, but rather a separate process of biometric verification.

AI systems in migration as high risk [❔]

A number of systems in the migration context pose a serious and fundamental risk to fundamental rights, including the right to seek asylum, but also privacy and data protection in border surveillance contexts. Civil society, in particular the #ProtectNotSurveil coalition, called for, at the very least predictive analytic systems and border surveillance systems to be high risk and subject to safeguards.

Whilst it is possible that the latter will be categorised as high risk, predictive analytic systems will not. There is an ongoing dispute that predictive systems, when they do not personal data, should not be considered high risk. However, as civil society has demonstrated, a number of fundamental rights concerns remain for the use of predictive systems, including the extent to which they can impact the ability to access international protection.

Accessibility requirements for high risk systems [✅]

Civil society recommended to EU lawmakers that the AI act ensure horizontal and mainstreamed accessibility requirements on developers of all AI systems. Whilst this recommendation is unlikely to be followed in full, we predict that a limited requirements on developers of high risk systems will be included in the EU AI Act.

Use of high risk systems registered in the EU AI database [✅]

The creation of a European Union-wide database marks a significant stride towards basic transparency on AI within public administration. Nevertheless, it’s essential to note that the current scope of the database is confined to high-risk systems only. From our perspective, there is a compelling case for expanding the database to encompass a broader range of systems, ensuring a more comprehensive and inclusive approach to transparency and accountability in public administration.

High risk systems in law enforcement/ migration registered in the public database [❌]

Despite positive progress on public transparency for uses of high risk AI in the public database, the Council have resisted public transparency for high risk AI used in law enforcement and migration.

Whilst civil society have argued that the use of AI by police, security and migration authorities requires more, not less transparency due to the vast consequences for human and procedural rights, Member States have insisted that information about high risk AI systems in these areas should not be revealed to the public. Discussions are ongoing as to whether ‘partial’ public transparency for such uses can be allowed. EU negotiators must ensure public transparency for the use of AI by law enforcement and migration actors, requiring registration of use on the database.

Fundamental rights impact assessment for high risk systems [✅]

It is encouraging that the EU institutions seem to have agreed that fundamental rights impact assessments (FRIAs) are an important tool of accountability for high-risk AI systems. The requirement for the deployers of high-risk systems to assess their impact on fundamental rights before putting their system into use in a specific context will guarantee that potential AI harms are identified and prevented throughout the system’s life cycle, and not only by those who develop the system.

However, it is still uncertain whether all high risk deployers will also have to publish the FRIA, or if this requirement will be limited to public sector deployers, as well as to what extent civil society and affected communities will be meaningfully involved in the process.

Civil society has called for FRIAs to be conducted by all high-risk deployers as fundamental rights risks are not less severe when they arise from the use of an AI system by a private company, e.g. in the workplace. We have also recommended to ensure that those likely to be impacted by the AI system and civil society experts contribute to the assessment as they can provide unique perspectives which could otherwise not be taken into account.

Rights of affected people – rights to complaint and explanation [✅]

Whilst the full range of rights and redress recommendationsoutlined by civil society are unlikely to be accepted, the negotiations are likely to include a right for affected persons to complain to a national supervisory authority if their fundamental rights have been violated by an AI system regulated by the legislation. In addition, individuals will have a right to seek an explanation and further information when they are affected by high-risk systems.

***

EU negotiators, in particular Member States, still have the opportunity to guarantee human rights in the EU AI Act. For more detail on the fundamental rights recommendations of civil society, read our statement.

Thanks to Sarah Chander, Karolina Iwańska, Kilian Vieth-Ditlmann, Mher Hakobyan, Judith Membrives, Michael Puntschuh and Ella Jakubowska from the AI core group for their contributions to this blog.