16 countries burned Poland’s bridges on the CSA Regulation: What now?

Poland’s surprising compromise to ease the deadlock on the CSA Regulation – which has been stuck in the Council of EU Member States for the past three years – met with failure. This blog recaps the Polish compromise, the positions of the Member States on the proposal, and what it could mean for the future of one of the most criticised EU laws of all time.

Chat Control still stuck in a stalemate

The European Commission’s proposed CSA Regulation – nicknamed Chat Control – has now been at an impasse in the Council of EU Member States for three years. The proposal faced overwhelming concerns about its incompatibility with EU’s fundamental rights and criticism from a broad range of stakeholders.

The last six Council presidencies failed to to assuage concerns over mass surveillance and encryption in the controversial proposal which is dividing the two camps. On one side, there are member states who support the mass scanning and encryption-breaking measures, such as Ireland and Spain. On the other side is the ‘blocking minority’ standing against Chat Control, including countries like Germany and Netherlands. These are the member states who either oppose mass surveillance measures in the Regulation, or who are undecided on their stance, thus thwarting this disastrous proposal from proceeding to the next step.

When Poland took over the EU Council presidency from January to June 2025, they tried a new approach. For the first time in the Council, there was a genuine attempt to build a compromise text which would eliminate the most alarming elements of the Commission’s proposal. However, the 16 Member States who support mass scanning and encryption-breaking measures refused to engage meaningfully with Poland’s attempts at compromise.

The unprecedented approach of the Polish Presidency

The country holding a Council Presidency takes on the role of putting forward compromise texts on Commission-proposed laws which bridge the different positions. On the CSA Regulation, the Polish Presidency put forward a compromise proposal in January 2025, the key aspects of which remained untouched in the later version:

- to remove detection orders completely (the requirement for entities like WhatsApp or Signal to scan the private communications of part or all of their user base), and allow instead for scanning to continue on a voluntary basis forever (for both known and new CSA materials as well as grooming). However, voluntary detection would be considered a risk-mitigation measure under Article 4, which may still incentivise voluntary detection measures. Worryingly, a review clause was inserted based on which mandatory detection orders could be brought back into the text three years after the law being passed.

- to rule out the breaking of end-to-end encryption, including ruling out its circumvention via a technique known as ‘client-side scanning’. However, the bizarre requirement for providers to cooperate on developing new scanning technologies remains.

While the Polish proposal was far from perfect (after all, Poland wanted to get support from Member States other than those from the blocking minority), it was the first real attempt at bridging the two sides in a genuine way.

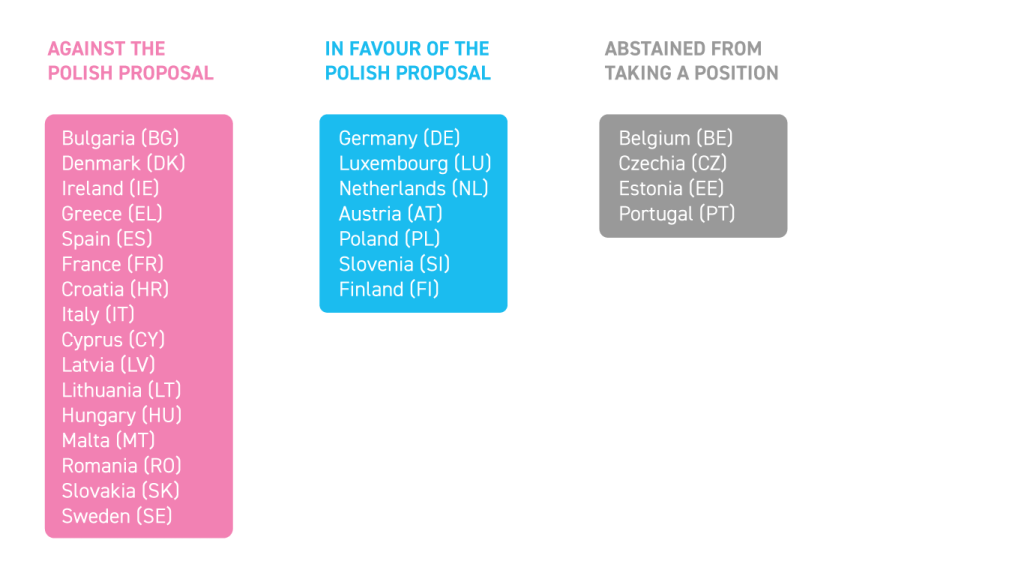

However, the 16 Member States, who advocated for the law to maintain its original mass surveillance and encryption-breaking measures (see image below), refused to budge even a single inch from their position. Since Poland did not back down on its rights-protecting approach, these countries stood in the way of a meaningful and technically-feasible solution until the very end.

Pink = against the Polish proposal | Blue = in favour of Polish proposal | Grey = abstained from taking a position (source; while these are the positions expressed on the January 2025 text from Poland, no change of position was found in the minutes from later meetings on the updated text.)

Is the blocking minority likely to be broken?

In order for the Council to reach an agreement, a minimum of 15 Member States, collectively representing at least 65% of the EU population, would need to agree to a text.

The 11 Member States that have actively supported (blue) or abstained from voting (grey) on Poland’s text represent only 42.43% of the population and do not meet the 15-country threshold. While this means that they are not enough to ensure the Polish compromise is agreed to, it’s also a good sign. It means that countries representing 42.43% of the EU population do not support untargeted detection orders or the breaking of encryption.

The pro-Chat Control camp, those supporting the mass surveillance agenda, has more adherents – 16 member states (pink). Despite their larger number, these countries still only represent 57.57% of the population, failing to reach the threshold required.

The 11 countries stopping the pro-Chat Control camp from achieving a sufficient majority to pass the law are therefore referred to as the “blocking minority”.

Some member states with a larger population ‘weigh’ more than others for reaching the threshold. In this case, it means that the CSA Regulation will only move forward if one of three unlikely scenarios happened:

- if either Germany or Poland were to change their position; or

- if the Netherlands and at least two other smaller countries changed their position; or

- if at least four other Member States switched sides.

However, we’re closely following national developments which could indeed lead to changes in some countries’ positions:

- The coalition agreement of the new Belgian government states that CSA is a “high priority” to be tackled by “supporting the work at EU level”, but does not specify how (page 10, in FR/NL).

- Germany’s new government has not taken an official stance on the file yet

- Czechia’s parliamentary elections on 3-4 October 2025.

- Elections in the Netherlands on 29 October 2025 after the Dutch government recently fell

These changes in governments mean that there is a need to keep up national pressure to ensure that member states do not agree to any CSA Regulation text until it rules out mass surveillance and protects end-to-end encryption.

What does the failure of the Polish proposals imply?

Before Poland, the Council had seen every presidency work on a compromise text which followed the spirit of the Commission’s proposal, despite the Council Legal Service’s scathing analysis of said proposal, and despite the existence of a well-established blocking minority of member states raising concerns. There was a succession of six presidencies pushing Chat Control, including Hungary, Belgium and Spain, which ended in a failure to secure a majority.

It was thus refreshing to see a different path being taken by Poland. However, as noted, this approach also ended up being unsuccessful. Therefore, the deadlock is set to remain in place for a long time, which is reassuring in terms of preventing Chat Control, but disappointing when it comes to finding a sustainable, realistic and meaningful solution to the serious issue of online CSA materials.

Under such circumstances, one logical way forward would be for member states to ask the Commission to withdraw the original CSA proposal, like France did, and to start working with all relevant stakeholders to propose structural remedies that address the problem.