Danish DPA approves Automated Facial Recognition

On 13 June 2019, the Danish football club Brøndby IF announced that starting in July 2019, automated facial recognition (AFR) technology will be deployed at Brøndby Stadium. It will be used to identify persons that have been banned from attending Brøndby IF football matches for violations of the club’s own rules of conduct. The AFR system will use cameras that scan the public area in front of the stadium entrances, so that persons on the ban list can be ”picked out” from the crowd before reaching the entrance.

The use of AFR technology at Brøndby Stadium comes with prior approval from the Danish Data Protection Authority (DPA) which is a requirement in the Data Protection Act, as explained below. Brøndby IF is the first company to secure an approval for using AFR in Denmark.

Under the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), biometric data for the purpose of uniquely identifying a person constitutes sensitive personal data (special categories of personal data in Article 9). This covers AFR. Article 9(1) of the GDPR prohibits the processing of sensitive personal data unless one of the conditions in Article 9(2) applies. The explicit consent of the data subject [Article 9(2)(a)] is one of these conditions, and generally speaking the most relevant one for private controllers. Consent cannot be the legal basis for using AFR at a football stadium though, since consent must be voluntary.

GDPR Article 9(2)(g) allows processing of sensitive personal data if the processing is necessary for reasons of substantial public interest, on the basis of EU or Member State law, which must be proportionate to the aim pursued. The law must provide for suitable and specific measures to safeguard the fundamental rights and the interests of the data subject.

Based on Article 9(2)(g), the Danish GDPR supplementary provisions (“Data Protection Act”) contains a general carve-out from the prohibition of processing sensitive personal data. Section 7(4) of the Data Protection Act provides that ”the processing of data covered by Article 9(1) of the GDPR may take place if the processing is necessary for reasons of substantial public interest.” Prior authorisation from the DPA is required for controllers that are not public authorities, and this authorisation may lay down more detailed terms for the processing.

Denmark has no specific national law providing a legal basis for the use of AFR by controllers along with suitable safeguards for data subjects. However, Section 7(4) can be used to allow any processing of sensitive personal data by law, including AFR, assuming that the threshold of substantial public interest is met. The explanatory remarks of Section 7(4) state that the provision must be interpreted narrowly, but the actual scope of the open-ended derogation is left to administrative practice by public controllers and authorisation decisions by the DPA for processing by private controllers.

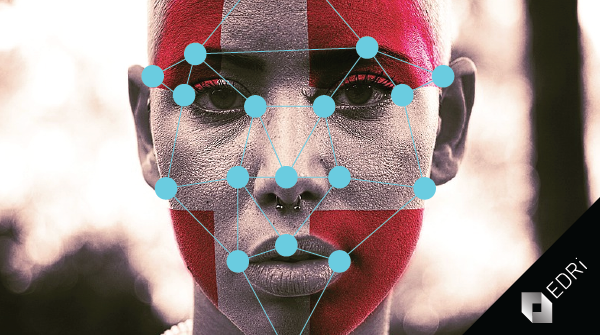

With the authorisation to Brøndby IF, the Danish DPA has decided that the processing with AFR to enforce a private ban list is necessary for reasons of substantial public interest, and that the processing is proportionate to the aim pursued. The logic of that decision is rather difficult to understand in the present case. AFR is one of the most invasive surveillance technologies since a large number of persons in a crowd can be identified from their biometrics (facial images) and automatically catalogued based on matches with pre-defined watch lists. At the same time, AFR is a very unreliable and inaccurate technology with known systematic biases in the form of higher error rates for certain ethnic minorities.

At Brøndby Stadium, AFR will be used to process sensitive personal data of, on average, 14000 persons per football match. The ban list currently contains only 50 persons, and there is no information available about how many of these 50 persons are actually trying to circumvent the ban and get access to Brøndby Stadium. There is also no pressing public security need for using this very invasive surveillance technology. The number of arrests by the Danish police in connection with football matches is at a record low, and rather ironically the Brøndby IF press release even highlights that there has been a positive development regarding security at Danish football matches over the last ten years. This evidence must, at the very least, call into question the proportionality of using AFR, even before considering whether there are really reasons of substantial public interest involved.

To the Danish newspaper Berlingske, the Danish DPA commented that there is no rigid definition of ”substantial public interest”. In the application from Brøndby IF, the DPA has considered the issue of security for certain sports events with large audiences. The DPA further told Berlingske that AFR would allow for more effective enforcement of the ban list compared to manual checks, and that this could reduce the queues at the stadium entrances, lowering the risk of public unrest from impatient football fans standing in queues.

The claims for the effectiveness of AFR are contradicted by the findings of independent evaluations of the technology. A report by the UK civil liberties organisation Big Brother Watch analyses the use of AFR by the Metropolitan Police and the South Wales Police at festivals and sports events, deployments comparable to the plans of Brøndby IF. Evidence obtained from the UK police through freedom of information (FOI) requests documents that 95% of the AFR matches are false-positive identifications. Persons are ”identified” by the AFR technology without being on a watch list. The obvious conclusion is that AFR is simply not a reliable and accurate technology for identifying persons in a large crowd. The unreliability of AFR could also affect the legality of using the technology since one of the GDPR principles in Article 5(1)(d) is that personal data must be accurate. AFR matches are personal data, but very far from being accurate.

It is unclear whether the reliability of AFR, or rather the lack thereof, has played any role in the DPA decision to grant authorisation for using AFR at Brøndby Stadium. Brøndby IF seems to assume that AFR is an almost perfect technology. The press releases claims that the AFR system will not be able to identify or register persons who are not on the ban list, implicitly ruling out any false-positive identification. Needless to say, this claim is demonstrably wrong. The authorisation from the DPA does not mention accuracy of AFR, and there are no specific requirements for the controller to take measures to limit false-positive identifications or even keep track of the magnitude of this problem. The “more detailed terms” set by the DPA in the authorisation to Brøndby IF add little to the ordinary GDPR obligations for controllers.

Danish EDRi member IT-Pol publicly criticised the plans for deployment of AFR technology at Brøndby Stadium. The threshold set by the Danish DPA in terms of requirements for a substantial public interest and proportionality seems very low, and this could lead to a large number of applications for using AFR by other private controllers in Denmark. Indeed, within just two days of the Brøndby IF press release, another Danish football club (AGF) expressed an interest in using AFR at its stadium and in exchanging biometric information about persons on ban lists with Brøndby IF. Incidentally, AGF has recently installed a new video surveillance system which is able to use AFR although the AFR functionality is currently deactivated in the system. Since AFR is largely about software analysis of captured video images, there is probably a large number of modern video surveillance systems in Denmark where AFR functionality could potentially be activated, perhaps through a software upgrade.

IT-pol

https://itpol.dk/

English translation of the Danish Data Protection Act (GDPR supplementary provisions)

https://www.datatilsynet.dk/media/6894/danish-data-protection-act.pdf

Face Off: The lawless growth of facial recognition in UK policing, Big Brother Watch (May 2018)

https://bigbrotherwatch.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Face-Off-final-digital-1.pdf

Association warns against new technology: fans should complain, DR Nyheder (only in Danish, 13.06.2019)

https://www.dr.dk/nyheder/indland/forening-advarer-mod-ny-teknologi-paa-stadion-fans-boer-klage

(Contribution by Jesper Lund, EDRi member IT-pol, Denmark)