Guide to the Code of Conduct on Hate Speech

On 31 May, the European Commission, together with Facebook, YouTube (Google), Twitter and Microsoft, agreed a “code of conduct” (pdf) on fighting hate speech.

We believe that the code of conduct will damage enforcement of laws on hate speech, and undermine citizens’ fundamental rights. In a joint press release, EDRi and Access Now have therefore announced our decision to leave the Internet Forum. In this blogpost we explain our analysis. The quality, effectiveness, predictability and review processes for existing laws is a separate and important issue, which we will not address in this post.

From the European Commission’s perspective, the scope of the agreed code of conduct is that messages containing hate speech will be deleted quickly. Hate speech is defined in the 2008 Framework Decision on Racism and Xenophobia, which requires EU Member States to ensure that the intentional public incitement “to violence or hatred directed against a group of persons or a member of such a group defined by reference to race, colour, religion, descent or national or ethnic origin” to be made “punishable”.

So, what happens to illegal online material under the “voluntary” code of conduct?

Firstly, the code recognises that the companies are “taking the lead on countering the spread of illegal hate speech online.” It seems peculiar that either the European Commission or the EU Member States should not to take the lead.

In a society based on the rule of law, private companies should not take the lead in law enforcement, theirs should always have only a supporting role – otherwise this leads to arbitrary censorship of our communications.

Secondly, the companies agree to prohibit the promotion of incitement to “violence and hateful conduct”. This is in addition to the often very broad, unpredictable and vague prohibitions that are already in their “community standards” for example, Facebook allows images of “crushed limbs” but not breastfeeding photos. It is important to note that the code does not refer to “illegal activity” here:

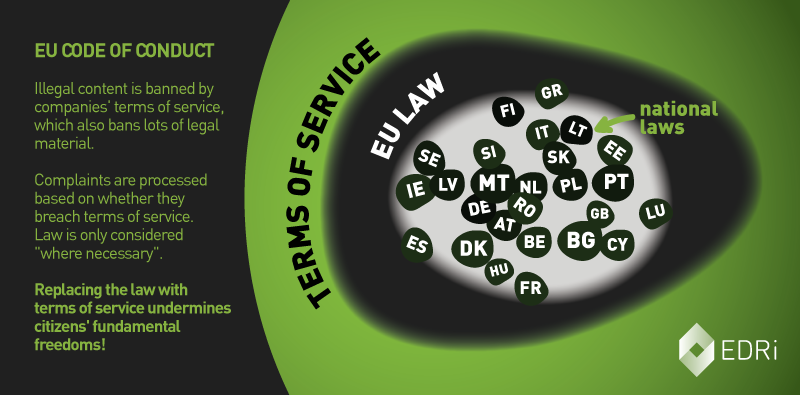

This creates a problem because internal rules are mixed together with legal obligations, with no clear distinction between them – it then becomes unclear what is against the law and what is not, what is legitimate speech and what is not.

Thirdly, when the companies receive a “valid removal notification” (not an accusation of illegality), they will review it against their terms of service, not against the law. Only “where necessary”, would the notification be checked against national laws. In practice, as illegal activity will be banned by terms of service, it will never be “necessary” to check a report against the law.

This is problematic since alleged “hate speech” will be deleted based on community guidelines, the companies will not possess evidence of something that they recognise as being civil or criminal offence. This also means that nothing will be forwarded to Member State authorities. Ultimately, this means that the author of a criminal or civil offence will not have to worry about being punished. Or repeating the offence.

On the other hand, the code of conduct also “encourages” civil society organisations to report content that violates the terms of service. Again, civil society organisations are not being trained to report violations of the law, but of the contracts users have with these four companies.

This is part of a wider trend to over-reliance on companies’ terms of service (see for example Europol’s work with IT companies).

In the code of conduct, there is not a single mention about the essential role of judges in our democratic societies. There is no mention about the enforcement of the law by public authorities. At each crucial point where law should be mentioned, it is not.

Conclusion

The European Union is founded on crucial human rights principles, including that restrictions should be provided for by law. Giving private companies the “lead” role in dealing with a serious societal problem and replacing the law with arbitrary implementation of terms of service is not a durable answer to illegal hate speech. Ignoring the risk of counterproductive impacts is reckless. At the same time as not solving the problems that this code was created to address, it undermines fundamental freedoms.