Locating climate justice in digital rights work at the EU level

A new study commissioned by EDRi acknowledges the complexities and environmental impacts of technological solutions, emphasising the need to bridge climate justice and digital rights. This is particularly relevant as the European Union views sustainability and digitalisation as twin and interconnected pillars.

In February this year, the EU’s Copernicus Climate Change Service reported the world’s first year-long breach of 1.5 degrees celsius warming, the threshold agreed upon by leaders now known as the 2015 Paris agreement. If exceeded consistently, this can lead to irreversible consequences for people and planet alike. Globally, governments are responding to the crisis of droughts, wildfires, heatwaves, and floods with a mix of legislation and investment in technological innovation – even as climate-vulnerable populations* lack digital access and the internet is inundated with climate denialism. Within the European Union (EU), sustainability and digitalisation are framed as two mutually-reinforcing processes key to taking action on climate without jeopardising economic growth.

In our work against biometric mass surveillance, for example, we have already seen how techno-solutionist approaches dominate. Amidst the challenges posed by climate change, lawmakers’ responses are no different. Techno-solutionist narratives have extensively permeated EU discussions and legislative processes, with technology frequently touted as a rapid and secure remedy for intricate societal challenges, including the proliferation of harmful, and sometimes illegal, online content. In the context of the upcoming EU elections, we have observed a recent surge in certain political quarters seeking to downplay the significance of the European Green Deal, concurrently championing a vision of digitalisation that does not inherently prioritise human rights and societal welfare.

But technology and the internet as we know it are not without their own environmental impact, making the zealous adoption of technological solutions to the climate crisis a complicated undertaking. Private electric vehicles reduce the consumption of fossil fuels, but depend on the extraction of finite critical raw materials; renewables like solar and wind are accelerating land-grabbing from agricultural smallholders; data centres have introduced competition over water between local residents and Big Tech; and the impact of 5G infrastructure on ecosystems is still under-researched. The utilisation of technology further solidifies current practices of surveillance and excessive control over marginalised populations. Consequently, this exacerbates prevailing power imbalances, which are also evident in the plight of climate-vulnerable communities. These emergent issues are propelling civil society organisations, scholars and community groups to explore the changing stakes of climate justice and digital rights, two spaces that have not always been in conversation with each other. Some EDRi members are already invested in critical laws and policies in this regard, such as digital sustainability (Forum of Computer Scientists for Peace and Social Responsibility) and advocacy against repressive surveillance of earth defenders (Privacy International, European Center for Not-for-Profit Law).

Deeply mindful of these trends, EDRi commissioned a mapping exercise by Dr. Madhuri Karak, to inform our strategic engagement with climate justice issues in Europe. This is especially relevant during a critical election year that will involve debates over green technologies, digital sustainability, and ensuring access to raw materials. The work of EDRi members like FSF, at the intersection of digital rights and climate/environmental justice, and internal reflection on how best to identify opportunities for climate justice considerations in digital rights work at the EU level, provided additional motivation in this endeavour.

The mapping exercise involved semi-structured interviews with thirteen individuals spanning digital rights and climate justice fields in the EU, from organisations representing civil society, academia, and policymaking spheres. Two common concerns surfaced across the board: first, a preponderance of MEPs regard technology as a force for good that can reverse the climate crisis; and second, digital rights advocates’ focus on how technologies are used (function) is considered a separate domain from climate groups’ emphasis on how and where technologies are manufactured (provenance).

Caption: The ‘word cloud’ below illustrates topics most frequently referred to by all 13 interviewees.

Both concerns prove the need for organisations like the EDRi network to i) proactively contribute to, and elevate ‘tech realist’ perspectives on the climate crisis that challenge the predominant narrative of tech optimism; and ii) highlight connections between the socio-environmental impact of raw materials extraction and the use of raw materials as a critical component of everyday life. Building on these common concerns, four themes were further identified in the research as key to possible next steps and strategy to be undertaken by the field when it comes to climate justice/digital rights issues in Europe:

i. Disseminating in-depth tech and digital rights expertise to climate justice actors in advocacy, research, and philanthropy

Organisations like EDRi and its members can consider bringing a climate justice lens to digital rights topics that fall under our core work on data governance, platform accountability, and the role of technology in society writ large. The aim will be to nurture internal capacity on topics that are intersectional in scope. Externally, the EDRi network could offer its domain knowledge to strategic climate litigation efforts against false climate solutions and support grantmakers on the risks and impacts of tech and data tools for ecosystem monitoring. Finally, exploring synergies between a demand like limiting the energy consumption of AI and the platform accountability campaigns that led to legislations like the Digital Services Act can bring ongoing tech advocacy into closer conversation with climate justice agendas.

ii. Articulating organisational mission to external partners

In order to be clear on the vision and how this work is undertaken, some respondents have suggested building on insights from the ‘Decolonizing Digital Rights’ exercise led by EDRi and Digital Freedom Fund through 2021-3, and EDRi’s 2024 manifesto which commits to a holistic analysis of problems, be it the power of Big Tech or the climate crisis.

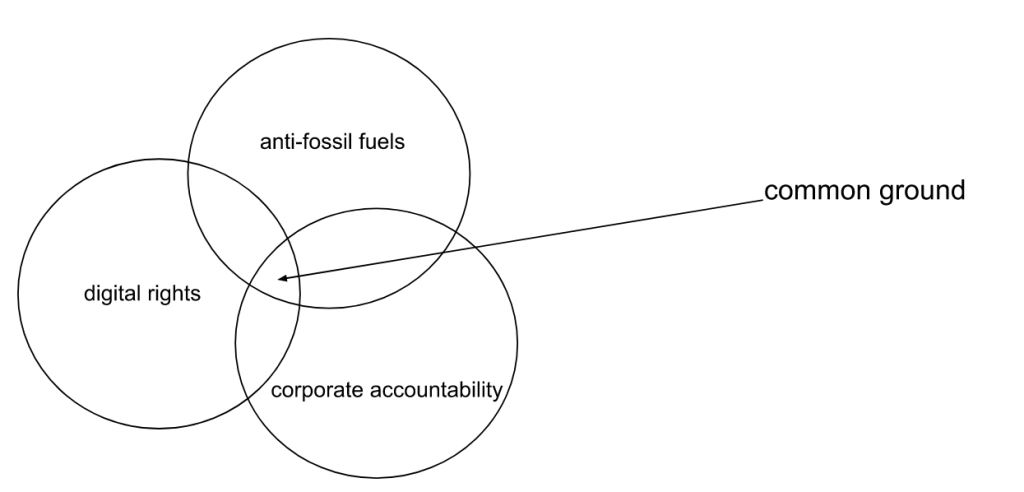

Caption: The mapping exercise revealed three distinct topical clusters in interviewees’ areas of work: corporate accountability, advocacy against fossil fuel companies, and digital rights. Consolidating the ‘‘common ground’ within will be critical to moving the needle on an intersectional advocacy platform in 2024.

A ‘common ground’ can emerge by inviting others to explore this intersectional space altogether because all three topical clusters share significant overlap in their analyses of the challenges in hand. For example, the EDRi network can unite a critical analysis of the business model of Big Tech that relies on the extraction of individuals’ data with the demand for reducing the environmental impact of these data infrastructures.

iii. Co-discovering entry points for advocacy

Creating an intersectional advocacy platform is the need of the hour as 2024 EU elections draw nearer. New legislations like the Net Zero Industry Act once again prove that debates over subsidies for ‘green tech’ manufacturing within the EU and regulating agricultural emissions will only grow. One interviewee suggested using this moment of political urgency to join forces and bring people together under a shared umbrella. For example, making human rights one of the cornerstones of how we collectively navigate transformations in our material-digital worlds would resonate with climate justice actors who are also interested in a ‘rights-based approach’ that encompasses digital access, livelihoods, health, and freedom.

iv. Contribute to existing coalitions instead of building new ones

The EDRi network can consider contributing to existing coalitions and networks at the intersection of climate justice and digital rights. As the convenor of a pan-European network of 50+ NGOs, experts, advocates and academics, EDRi is well-suited to support members to define its operations in this line of work.

Specifics of the electoral outcome in June 2024 notwithstanding, the climate crisis and how we decide to collectively tackle it will be a key pillar of the new EU mandate. EDRi members and other allies can endeavour to cultivate a shared understanding of the interlinked challenges embodied by the climate emergency and online harms in order to establish a ‘common ground’, thereby laying a solid foundation for collaborative efforts. Moreover, fostering an environment conducive to free and open discussions will serve as a catalyst for the exchange of ideas, insights, and perspectives, thereby enriching collective knowledge and understanding in all shared areas of interest.

By embracing transparency and inclusivity as core principles of EDRi’s vision and functioning, stakeholders will be able to craft solutions that address the needs and aspirations of diverse communities navigating the twinned complexities of our digital society in a time of climate change.

Acknowledgements: Alejandro González (SOMO), Bram Varken (Corporate Europe Observatory), Christian D’Cunha (European Commission), Claire Fernandez (EDRi), Desiree Zeljka Milošević (Klimerko), Diego Naranjo (formerly EDRi), Fieke Jansen (University of Amsterdam), Itxaso Dominguez de Olazabal (EDRi), Jan Tobias Mühlberg (Université Libre de Bruxelles), Karolina Iwańska (European Centre for Non-Profit Law), Louise Fournier (Greenpeace), Maximilian Jung (Bits und Baume), Myriam Douo (Oil Change International), Narmine Abou Bakari (Greens/EFA), Nikita Kekana (Digital Freedom Fund), Robin Roels (EU Raw Materials Coalition), and Zuzanna Warso (Open Future).

Madhuri Karak, Ph.D.; Independent researcher (LinkedIn)

Itxaso Dominguez de Olazábal; Policy Advisor, EDRi (LinkedIn)

*The impact of climate change will not be experienced equally across nations or within communities. Histories of social, economic, and political inequalities alongside demographic indicators determine access to the knowledge, capacity, and resources essential for preparing, enduring, and adapting to these impacts, making already disadvantaged populations bear disproportionate risk from climate events. Bringing in this human dimension complements already prevalent risk and vulnerability assessments conducted for agriculture, fisheries, infrastructure, and energy sectors by governments. (go back up)

- Jansen, F., Gülmez, M., Kazansky, B., Bakari, N. A., Fernandez, C., Kingaby, H., & Mühlberg, J. T. (2023). The Climate Crisis is a Digital Rights Crisis: Exploring the Civil-Society Framing of Two Intersecting Disasters. Ninth Computing within Limits LIMITS. https://doi.org/10.21428/bf6fb269.b4704652

- Kazansky, B., Karak, M., Perosa, T., Tsui, Q., Baker, S., and The Engine Room. (2022). At the confluence of digital rights and climate & environmental justice: A landscape review. Available at: https://engn.it/climatejusticedigitalrights