Position Paper: New EU law amplifies risks of state over-reach and mass surveillance

The EDRi network published its position paper on the proposed Regulation on automated data exchange for police cooperation (“Prüm II”). The European Commission’s Prüm II proposal fails to put in place vital safeguards designed to protect all of us from state overreach and authoritarian mass surveillance practices. In the worst case scenario, we may no longer be able to walk freely on our streets as the new law would treat large parts of the population as a criminal before proven otherwise.

“What you’re saying is, for me to own a car and to drive, I have to submit that my photo and information are going to be used for policing purposes across the entire EU… Are we all walking around as citizens? Or are we all walking around as suspects?” – Carole McCartney, a law professor at Northumbria University, told Politico Europe regarding the proposal of the Council on the new law.

The Prüm framework offers a set of laws that regulate the automated sharing of personal data between the Member States for investigating certain crimes. The new proposal wouldfurther automate the cross-border sharing of personal (and often highly sensitive) data: people’s faces, fingerprints and DNA data, vehicle registration data and police records. The European Commission justifies the necessity for this expansion of powers that will amplify state over-reach and mass surveillance by saying that the free movement of people principle in the EU allows criminals to travel across Schengen countries. Therefore, data about them held by police authorities should be freely exchanged too. The Prüm framework not only threatens the right to privacy and data protection but also instrumentalises one of the fundamental principles in the EU – the free movement of people – to legitimise the need for even more policing.

Efficient crime investigations – or groundless over-policing?

What this means for us is that the sensitive data of up to 10% of the population – such as people’s DNA and fingerprint data – are being collected in national policing databases which can be searched automatically by each Member State. The system currently allows police authorities to compare a DNA profile – in theory, taken from a criminal suspect or found at a crime scene – and use it to run a search against all other participating member states’ DNA databases. The new proposal would allow searches on the basis of people’s facial images, too.

Since entering into EU law in 2008 (between 2005 and 2008, it was a treaty between several governments only) the Prüm framework has proven unfit for purpose. For example, in Slovenia, investigations have revealed that victims and their family members have been included in criminal databases, and other examples show that non-suspects, acquitted people, victims and witnesses are routinely included in criminal databases without a legal basis in many EU countries. Our research has also shown a patchwork of rules (or lack of rules) and systemic data protection failings across these national databases. When plugged into supranational systems like Prüm, the risks skyrocket.

Given the lack of transparency around these systems, many people are unaware that their data is being unfairly and unlawfully processed, and are unable to exercise their rights to redress. Yet their inclusion in these databases can have severe repercussions on their rights and liberties.

EDRi’s analysis has proven that the law which deepens over-policing and mistrust is not necessary or proportionate. Prüm jeopardises rights to justice, fairness and data protection that we have been vigorously fighting for, without sufficient evidence. And now, the European Commission wants to give even more access to data to police in the European Union.

“It appears to be a case of trying to get the police to run when they currently have problems walking.” – Chris Jones, Director, Statewatch

Prüm II: The expansion of police surveillance

In 2021, the European Commission published its proposal to expand the access to data, and therefore power, granted to police authorities under the Prüm framework. Their goal is to improve cooperation in tackling cross-border crimes. The new proposal adds facial images and police records to the list of the type of data that can be shared and further automates the process of data sharing.

Despite already having access to a wealth of personal data under existing Prüm rules, the European Commission wants to enable instant access to even more data, without addressing the serious risks or ensuring compliance with fundamental rights rules. Whilst the framework is long overdue for reform, the EDRi network argues that the expansion of data categories should be rejected, and any reform should focus on:

- tackling structural issues with the (mis)use of national police databases;

- establishing the necessity and proportionality of the Prüm framework;

- aligning data protection safeguards to the standards of the Law Enforcement Directive.

The EU’s new proposal, Prüm II, fails to make these improvements and creates additional serious risks to fundamental rights.

“Without serious improvements, the proposed Prüm II Regulation will be like pouring petrol on the fire that is the state of data collection, processing and cross-border exchange by law enforcement in Europe.” – Ella Jakubowska, Policy Advisor at EDRi

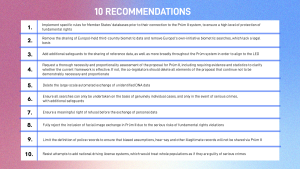

Check out EDRi’s recommendations on how the reform could be steered in a human rights-respecting direction.

Human rights in dire straits

We are witnessing the growing criminalisation of political opposition, social movements, refugees and migrants and investigative journalists. The Prüm II reform threatens to bring about even more policing and fewer safeguards for people. Rather than making us feel more secure by effectively tackling crimes, the rules could frame everyone as a criminal and – if the Council’s amendments are passed – would subject us to mass surveillance. These authoritarian practices allow police authorities to put limits on people’s privacy without sufficient reason or adequate safeguards. This is highly concerning news for everyone as it would put an end to the freedoms that come with privacy which help us go about our lives without constantly having to look over our shoulder, or feeling that we have to conform to someone else’s labels.

The system is, however, harsher on racialised and marginalised people as the use and composition of law enforcement databases often lead to more surveillance, coercive actions and abusive policing of these groups. The addition of police records will likely reinforce their overpolicing. Information contained in national police databases frequently includes gossip and hearsay, and lacks accuracy and legitimacy,

Additionally, individuals registered in a police database in a member state with lower thresholds for inclusion, weaker safeguards or less effective oversight mechanisms will be more likely to be subject to potentially unjustified police attention than individuals who benefit from higher national standards. As a result, they will be unfairly subject to a higher risk of intrusions upon their rights.

Read more about EDRi's work on Prüm

-

Press release: European Commission jumps the gun with proposal to add facial recognition to EU-wide police database

The European Commission has put forward a proposal to ‘streamline’ the automated sharing of facial recognition images and other sensitive data by police across the EU. What will...

-

Policing: Council of the European Union close to approving position on extended biometric data-sharing network

The Council of the European Union is close to reaching an agreement on its negotiating position on the 'Prüm II' Regulation, which would extend an existing police biometric...

-

Policing: France proposes massive EU-wide DNA sweep, automated exchange of facial images

The French Presidency of the Council is seeking EU-wide comparisons of every DNA profile held by police forces against all those held by other national police forces, as...

-

EDRi challenges expansion of police surveillance via Prüm

The Prüm framework permits police forces of EU Member States to exchange DNA files, fingerprints, vehicle data via a decentralised system. The European Commission and the Council are...