Poland searches for silver bullet for CSA Regulation

The Polish Council Presidency attempts to break the deadlock on the controversial 'Chat Control' proposal. We analyse the new approach and what could happen if Member States approve it.

‘Chat Control’ has been stuck for years

The EU’s proposed CSA Regulation – or as you may know it, ‘Chat Control‘ – has been stuck for years. In a dramatic attempt to push through the bill in December 2024, the Hungarian Presidency of the EU Council tried to publicly guilt-trip national governments into agreeing to their version of the proposal.

Thankfully, this strategy from Hungary did not work. Instead, it brought the depth of opposition to mass surveillance and/or breaking encryption from at least ten EU countries, including Germany, the Netherlands and Luxembourg, into the open.

Throughout the negotiations so far, representatives of the Polish government have criticised the proposal for being the wrong step to tackle child safety issues online. Yet in January 2025, the Polish Presidency joined the litany of countries that have attempted to break the Council deadlock.

A new approach from the Polish Presidency

Whilst far from perfect, this new Polish proposal is significantly better than the attempts made by their predecessors, Hungary and Belgium. In particular, this is because Poland has proposed to fully delete ‘Detection Orders’.

Detection Orders are the part of the original European Commission ‘Chat Control’ proposal that would have forced providers like Signal and WhatsApp to scan the messages of all users. This requirement would apply regardless of the fact that it would break encryption and would weaken the integrity and security of all services – for businesses and users alike.

Instead of having Detection Orders, Poland proposes to have only so-called ‘voluntary measures’. Heavily inspired by rules in the currently in force interim ePrivacy derogation, the new text would permit service providers to scan online content – but would not force them to do so.

What could happen if Poland is successful?

Whilst there are still a lot of open questions – and a significant number of countries opposing Poland’s attempts to protect end-to-end encryption – we reflect here on what would happen if this text made it to trilogues (negotiations between the Council and Parliament).

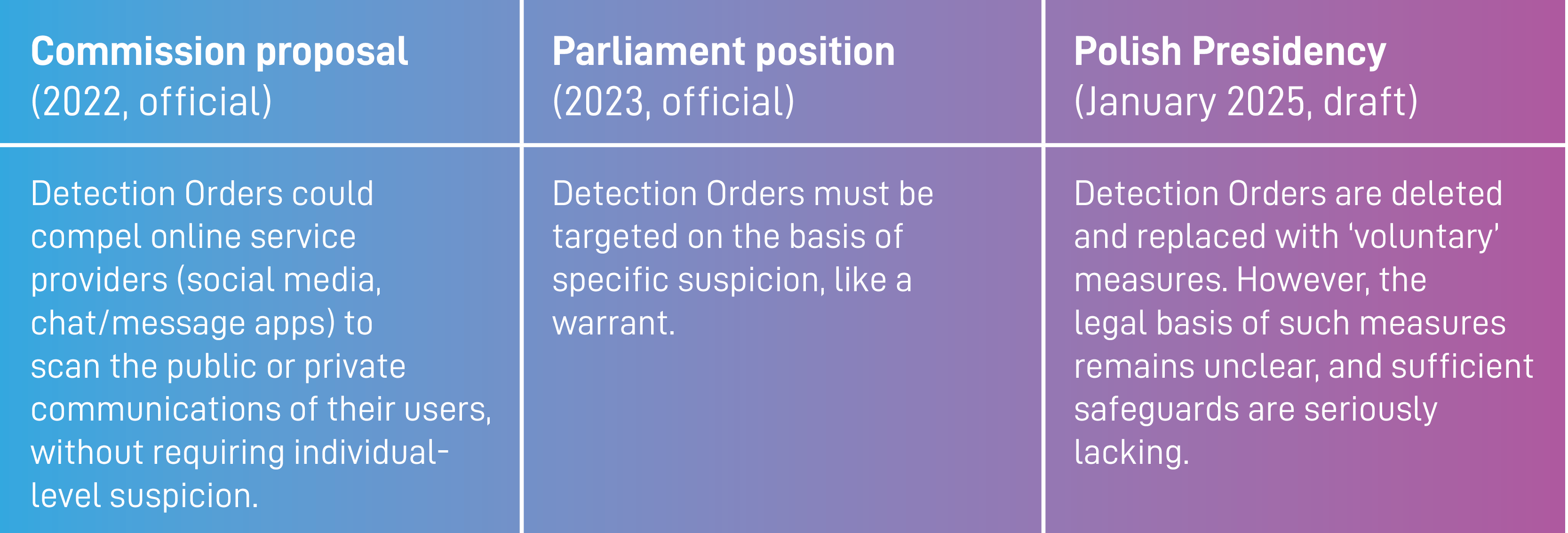

Detection orders

Detection orders are the most controversial component of the proposed CSA Regulation, because they can force interpersonal communications services (chats and messengers) to use AI tools to mass monitor private communications on the devices of users with Client-Side-Scanning. They can also require hosting services (cloud and social media) to use AI tools to assess all content that is uploaded (aka upload filters).

Detection orders: what could happen in trilogues

With such different approaches, it’s hard to know what common ground the co-legislators would find. That being said, both the Parliament and the (hypothetical) Council position would reject the mass/untargeted government-mandated scanning of innocent people’s private communications,. At the same time, ‘voluntary’ scanning can be as intrusive and harmful as when it is government-mandated – especially as the Polish proposal still requires hits to be reported to law enforcement.

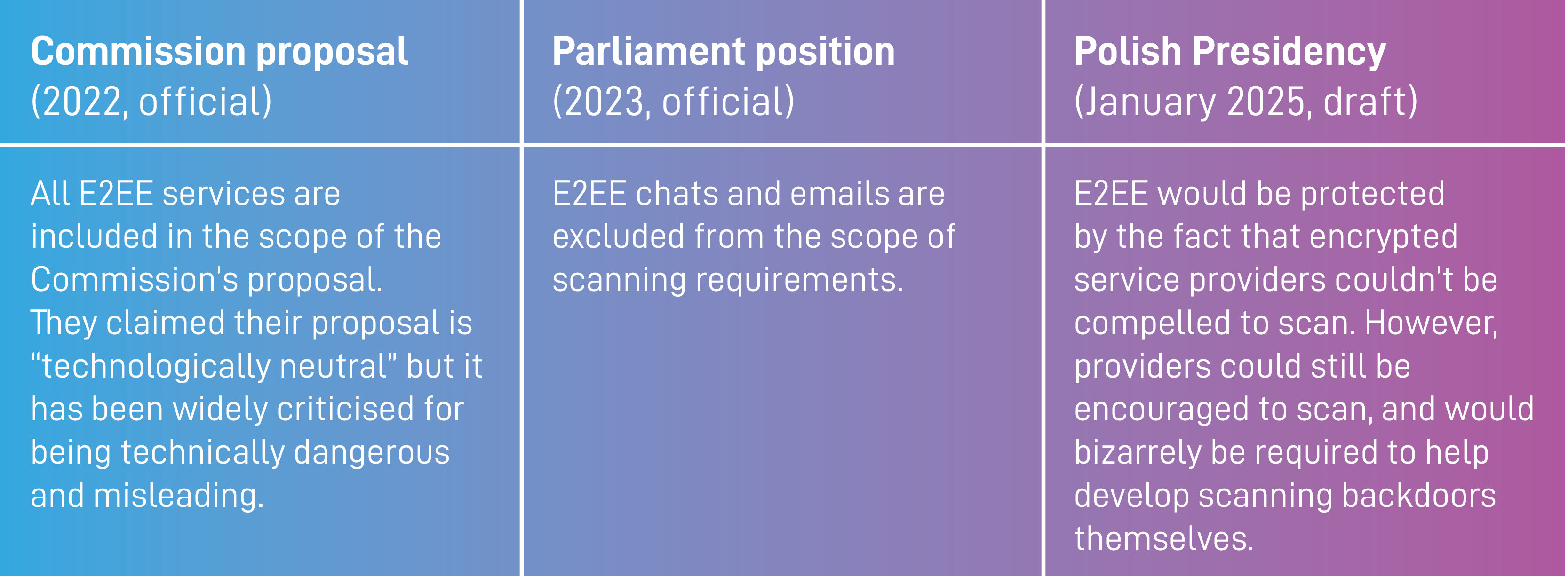

End-to-end encrypted (E2EE) services

End-to-end encryption is the foundation of modern communication services (chats, clouds, emails etc.). Encryption is essential to protect everyone’s personal information and confidential communications in digital spaces. It is also widely used by journalists, whistleblowers, civil rights defenders and others whose personal safety can rely on the confidentiality of their communications. Undermining encryption would make everyone less safe.

End-to-end encrypted services: what could happen in trilogues

Despite former Home Affairs Commissioner Ylva Johansson’s all-out war on encryption, there is clearly not sufficient political will to break encryption across Europe. Too right: doing so would impact every person that wants to communicate safely via digital platforms, including government representatives. The European Court of Human Rights has confirmed that encryption is a key part of the right to privacy in the twenty-first century. However, this issue is possibly the biggest challenge for the Polish proposal, as countries like Spain have admitted that the CSA Regulation is their chance to break encryption across the EU, and they will not be keen to give up this attack.

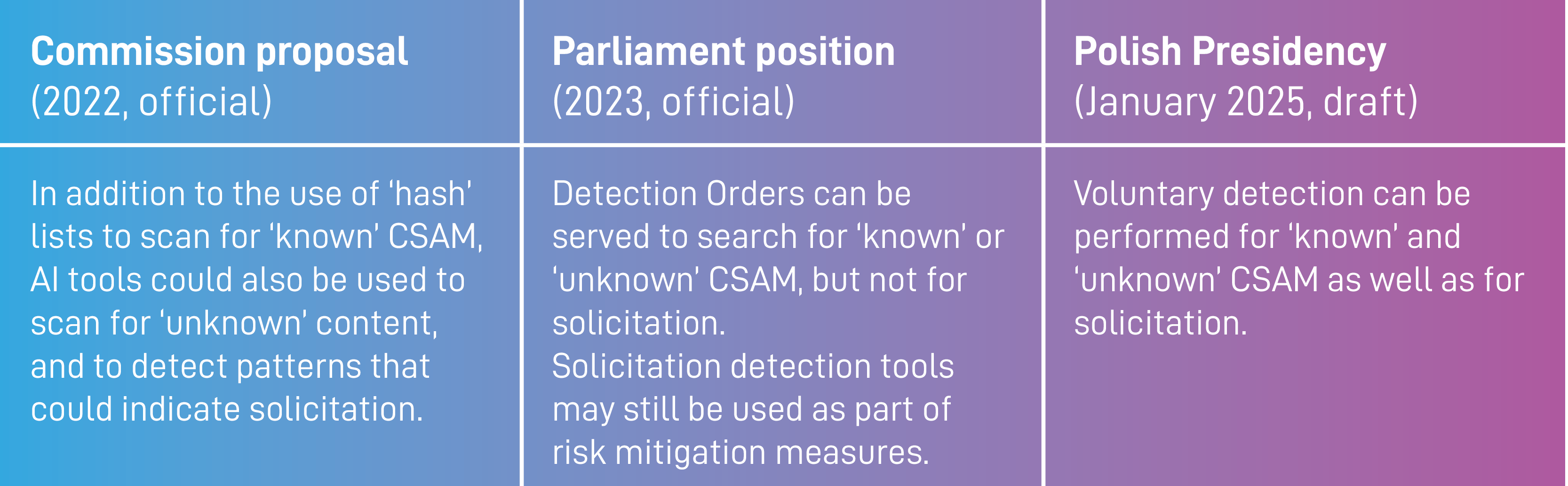

Scope of scanning

Three categories are distinguished for the potential scope of scanning: ‘known’ content (that has already been verified by authorities to be CSAM), ‘unknown’ (not previously identified) content, and to detect patterns that could indicate solicitation (grooming).

Scope of scanning: what could happen in trilogues

The co-legislators have only partially recognised the serious unreliability of tools to detect unknown CSAM or grooming. Whilst both Council and Parliament texts try to put safeguards on these scanning tools, neither text goes far enough, nor do they sufficiently recognise the inherent limitations of AI-based scanning technologies, as explained in our position paper. This could still lead to people across the EU being falsely accused of the crime of CSA.

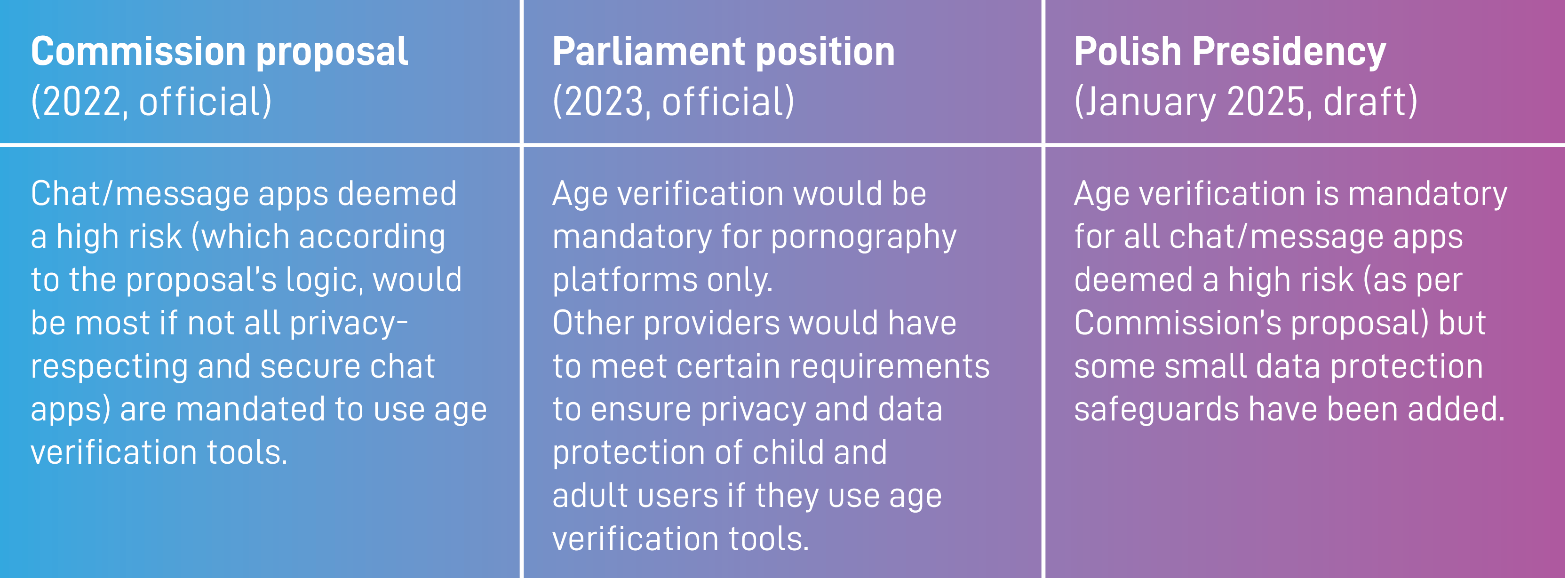

Age verification

Age verification is the process of predicting or confirming an individual’s age. Methods discussed to implement this include document-based age verification and biometric age estimation. Each approach includes risks and so far there is no EU-wide tool that could be considered compatible with children’s digital rights.

Age verification: what could happen in trilogues

With the current political fervour and techno-solutionism about age verification tools, we fear that any eventual outcome would see some mandatory age verification.

We argue that the CSA Regulation is the wrong place for such measures – which should be dealt with in a much more nuanced and careful way, and already have a possible legal basis in other laws (GDPR, DSA, AVMSD). Such a step would also go against the ability of providers to take a proportionate and risk-based approach. Mandatory age gating on all messenger services, especially given the lack of acceptable technical solutions, could lead to severe digital exclusion and prevent people from communicating with their friends and family.

Where does this leave us?

The future is still very unclear. The cynical politicisation of this law by DG HOME since 2022 continues to obfuscate the possibility of a resolution based on evidence and law, but it is positive that the Polish Presidency is seeking rights-respecting alternative to the Commission’s proposal.

More broadly, whilst negotiations in Brussels continue, the reality on the ground shows that governments are failing to meet even the most basic requirements to tackle online CSAM – as revealed by a new German documentary. In this context, the CSA Regulation can be little more than a sticking plaster over a broken system.

Whatever happens, EDRi will continue to fight for measures to tackle CSAM online to be implemented in a way that is effective, proportionate, and fully in line with the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the EU.

- EU Council (or just ‘the Council’): the institution made up of representatives of every EU Member State. The European Parliament and the EU Council are co-legislators of the EU, which means that they must agree on the text before any law can be passed;

- Council Presidency (or just ‘the Presidency’): every 6 months, a different EU country takes over the ‘Presidency’ of the EU Council, making them ultimately responsible for coordinating and negotiating all relevant legislation on behalf of their fellow EU Member States’ governments;

- Polish proposal: when we say ‘Polish proposal’, we are referring to the draft text that has been put forward by the Polish Presidency, with the aim of reaching a ‘General Approach’ (GA) (agreed position) of the EU Council. Even if agreed, this version of the law would still need to be negotiated with the European Parliament before it could enter into EU law;

- European Commission proposal: the original proposal for most EU laws is made by the European Commission. We say they have the ‘right of initiative’ because usually, they are the only EU institution that can propose a new legal text.