#PrivacyCamp22: Event Summary

The theme of the 10th-anniversary edition of Privacy Camp was "Digital at the centre, rights at the margins" and included thirteen sessions on a variety of topics. The event was attended by 300 people. If you missed the event or want a reminder of what happened in a session, find the session summaries and video recordings below.

This special online edition of Privacy Camp offered a forward-looking retrospective on the last decade of digital rights. Academics, activists and privacy experts from various backgrounds came together to build on the lessons of the past and collectively articulate strategic ways forward for the advancement of human rights in the digital society.

Emerging intersections within the realms of regulating digitalisation as well as within other broader social justice movements show that – while some issues remain timeless – the power struggles ahead might happen on new terrain(s). How can we adapt to these new terrains, while drawing on a decade’s worth of lessons? How can we organise with broader groups of people and other communities? What are the points of reflection we must focus on, to address the wider impact of the digital rights’ fight?

Check out the summaries below to learn which are these transcending power struggles and what are the ongoing efforts to build a people-centred, democratic society!

Contents

- Stop Data Retention – now and forever!

- Centring social injustice, de-centring tech: The case of the Dutch child benefits scandal

- Surveillance tech as misclassification 2.0 for the gig economy?

- Ministry of Microsoft: Public data in private hands

- The DSA, its future enforcement and the protection of fundamental rights

- A feminist internet

- EDPS Civil Society Summit 2022: Your rights in the digital era have expired: Migrants at the margins of Europe

- Drawing a (red) line in the sand: On bans, risks and the EU AI Act

- Regulating tech sector transgressions in the EU

- Connecting algorithmic harm throughout the criminal legal cycle

- Regulation vs. Governance: Who is marginalised, is “privacy” the right focus, and where do privacy tools clash with platform governance

- Regulating surveillance ads across the Atlantic

- How it started / how it is going: Status of Digital Rights half-way to the next EU elections

What was your favourite session this year?

Let us know by filling in this short surveyStop Data Retention – now and forever!

Session description | Session recording

Our fundamental right to privacy and freedom are at the core of our constitutional order, and they should be applicable in the digital world as well. Despite countless attempts for mass data retention bring struck down by the European courts, the European Commission and some EU member states are hoping to introduce measures of data retention in the Union. In July 2021, the Commission published a “non-paper” considering the legal options to introduce the indiscriminate retention of user data in some form or another.

This panel delved into why data retention is so intrusive. Data retained and accessed represent our daily movements, exposing our personal networks and connections, our health situation, political and religious beliefs, trade union affiliation, among others sensitive information. Member of the European Parliament (MEP) Patrick Breyer underlined that data collection and unregulated access to these databases have a chilling effect on democratic participation as people cannot freely protest and express their position if they are being watched. The speakers pointed out that even though the illegality and disproportionality of these practices have been proven by a Court of Justice of the European Union decision, several EU Member States are refusing to stop data retention.

The activist and artist from EDRi’s member Digitalcourage, Rena Tangens, reflected on the lessons from the past in challenging mass data retention to understand what actions worked well to mobilise people and influence policymaking. For example, a combination of art and advocacy motivated people to voice their concerns and exercise their democratic rights. Additionally, building a diverse coalition created a strong pushback and served as a representation of the depth and width of the precarious impact data retention practices have on us. Noémie Levain, a jurist at EDRi member La Quadrature du Net (LQDN), gave the example of LQDN’s litigation case in France which shows that political engagement is another useful and important tool to consider in future actions.

Centring social injustice, de-centring tech: The case of the Dutch child benefits scandal

Session description | Session recording

This panel brought together local anti-racist organisations to discuss digital rights first through the case of the Dutch child benefits scandal, and by reflecting on the broader context of digitalisation in the public sector. The Dutch child benefits scandal is a political scandal in the Netherlands where the Dutch Tax and Customs Administration wrongly accused an estimated 26,000 parents of making fraudulent benefit claims, requiring them to pay back the allowances they had received in their entirety. In many cases, this sum amounted to tens of thousands of euros, driving families into severe financial hardship. The speakers articulated the problems of technology and it’s intersection with social injustice, including the areas in which local anti-racist organisations lack capacity, how digital rights organisations can support their efforts, and how these communities can be built and sustained beyond these discussions.

The speakers highlighted that the issues of discrimination and racism linked to the use of algorithms and technology in the public sector are not new. These issues however can be exacerbated by new technologies, and new problems may emerge. The use of technology by governments function to normalise and rationalise existing racist and classist practices (e.g., Dutch childcare benefits scandal). These are active, political choices made by governments which tend to be obscured and distracted by focusing solely on algorithms and technology. Thus, we need to go beyond the legal and technical issues of transparency and biases, adopting a more interdisciplinary and multilinear approach to social issues and the use of technology, reviewing the problems in question as an entire ecosystem.

In relation to the prevailing use of technical and legal discourse in recognising and defining problems in the field, this often creates spaces that are expert-driven, despite the fact that these injustices occur and are inflicted upon communities who are usually not part of these discussions. The panel concluded that the digital rights field needs to think carefully about how they can build and offer safe spaces together with anti-racist activists and communities. This must start by truly listening and valuing people’s time. In some cases, rather than pushing for change outwards that can be (unintentionally) harmful to affected communities, we need to also look inward at our own respective spaces and environments, for example to call for change in the areas of academic funding and university-sponsored technological developments.

Surveillance tech as misclassification 2.0 for the gig economy?

Session description | Session recording

For almost a decade, gig economy employers have relied on sham contract terms to misclassify workers as independent contractors to deny them their statutory rights. Recently, some workers have been successful in asserting their rights in court. But the key to legal victory is proving that such workers are indeed under the direct management control of the employer and not truly independent. Algorithmic management and surveillance are intensifying across sectors as more hidden and sinister means of controlling workers.

Kicking off the conversation with an overview of the main definitions of gig workers, Kate McGrew, from ESWA, expressed strong criticism against the narrow conceptualisation of platform workers, pointing out that the field is much broader, including other forms of work like sex workers. Precarious and oppressive platform employment are more pronounced in the Global South due to poorer infrastructure, weaker enforcement of the rule of law and harsher treatment of precarious workers by law enforcement. One solution was the idea of demystifying the business model of these platforms, which are framed as an alternative to unemployment, ensuring that platform work is fair and transparent.

Platform workers who are bound by common experience, have a unique opportunity to build solidarity across industries and from north to south geographies to hold global platforms (like Uber, Amazon, Deliveroo) to universal standards of worker and digital rights.

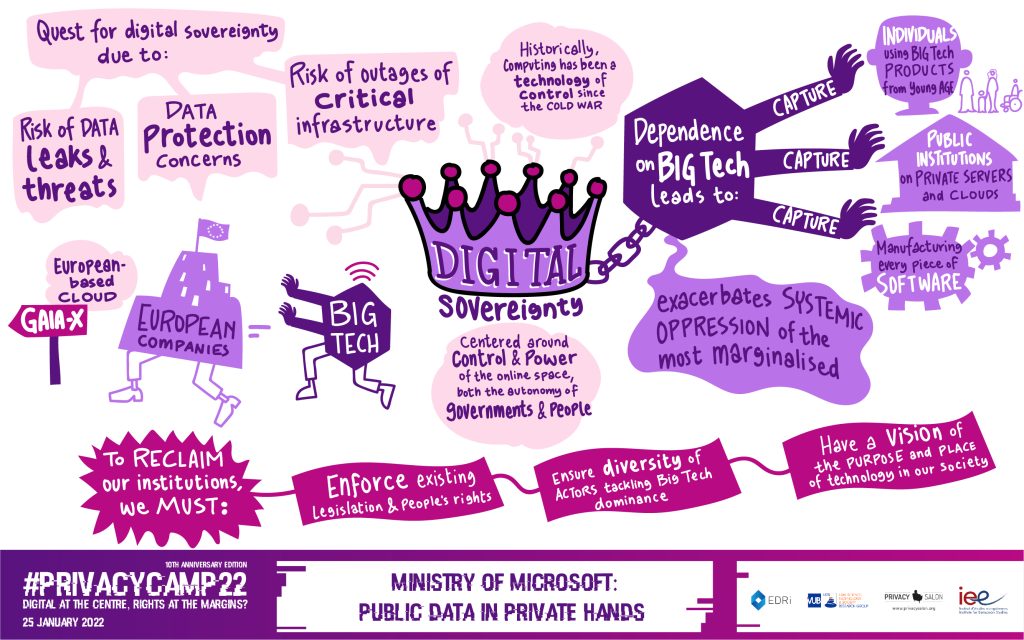

Ministry of Microsoft: Public data in private hands

Session description | Session recording

The session focused on concerns about digital sovereignty and the dependency of public powers on private infrastructures. From universities receiving “free” cloud storage from Google to states increasingly relying on Microsoft or Amazon cloud services, questions arise about sovereignty when crucial information is in the hands of for-profit organisations. Claire Fernandez, EDRi’s Executive Director, initiated the discussion by stating that digital sovereignty is centred around the control and power of the online space, both the autonomy of governments and people. Seda Gürses, from the Faculty of Technology Policy and Management, TU Delft, added that historically, computing has been a technology of control since the Cold War. And in simpler words, Frank Karlitschek, Founder and CEO of Nextcloud GmbH, defined digital sovereignty as being in control of your digital life and destiny.

The speakers reflected on the reason why the quest for digital sovereignty has increased. They talked about the risk of data leaks and threats, the EU-US data transfers, growing instability of critical infrastructures, misuse of data protection narratives to serve governments’ national interests, among others. In addition, they dived into the question of Big Tech dependence, which captures individuals who are used to Big Tech products from a young age; public institutions whose data/systems are on privately held servers and clouds; and every piece of manufactured software. In this Big Tech power grab, it is marginalised communities that have been oppressed the most as public institutions have failed to respond adequately to the rising monopoly and influence of Big Tech companies.

We must reclaim our institutions by enforcing existing legislation and people’s rights, ensuring diversity of actors tackling the dominance of Big Tech throughout the supply chain and not simply replicating Big tech’s infrastructure, and by having a vision of the purpose and place of technology in our societies.

The DSA, its future enforcement and the protection of fundamental rights

Session description | Session recording

The panel concentrated on the Digital Services Act (DSA) proposal, which aims at providing a harmonised regulatory framework for addressing online harms, while at the same time creating accountability for service providers and protecting users’ fundamental rights. The co-moderator Ilaria Buri, a researcher at University of Amsterdam, set the question of the enforcement of the DSA, underlying that lessons from the past have been learned. While the experience of the GDPR for example has shown that even when there is a strong enforcement framework, actual effective enforcement is not guaranteed, the DSA includes a proposal for centralising enforcement for certain actors.

Furthermore, Jana Gooth, Legal Policy Advisor/Assistant to MEP Alexandra Geese, added that the DSA text also foresees deadlines for the Digital Services Coordinators (DSCs), and the proposal opts for a more centralised approach for enforcement vis à vis Very Large Online Platforms, with the European Commission being identified as the main enforcer. Similar to the guarantee in the GDPR, the DSA needs to consider a situation where the enforcement agency can also be taken to court. However concerns with authorities’ limited resources, the lack of coordination between supervisory authorities, and the complexity of the One Stop Shop still remain.

A feminist internet

Session description | Session recording

This session advocated for a feminist internet and the need to empower our communities, working with technologies to do so. Communities of artists and advocates lack the structural resources to enable feminist hosting platforms to become sustainable in the longer term. The speakers elaborated on the urgency of technofeminist infrastructures in relation to the wider context of digital rights and addressed the challenges their mission entails in relation to an internal and external agency.

Mallory Knodel pointed out that feminism speaks to a variety of different interpretations (e.g., social justice, human rights, democracy). Feminism helps us to look at different conceptions, such as bodily issues which go beyond human rights issues. Technofeminist infrastructures are inclusive to the needs of diverse groups. For example, in the case of Latin-American organisations, many activists are at risk of attacks by right-wing groups, sexist groups, and even governments. Hence, they need extremely secure tools to protect themselves and their work – which may be different from feminist groups in Europe. One of the most important needs that technofeminism deals with is building more sustainable and safe spaces.

In the beginning the process of participation/exclusivity, is always slow, but strong relationships are formed in the long term. In relation to that, speakers discussed projects that could empower their mission and collaboration with like-mind projects such as combining different collectives, activating university resources, using opened-source projects and relying on solar energy to sustain servers.

EDPS Civil Society Summit 2022: Your rights in the digital era have expired: Migrants at the margins of Europe

Session description | Session recording

The European Data Protection Service (EDPS) Civil Society Summit provides a forum for exchange between the EDPS and Civil Society Organisations, to exchange insights on trends and challenges in the field of data protection and engage in a forward-looking reflection on how to safeguard individuals’ rights. In the past, the European Union (EU) and the Member States have restricted asylum and migration policies even further to prioritise the prevention of new arrivals, the detention and criminalisation of people who enter, return of people, and the externalisation of responsibilities to third countries. In this context, authorities have increased the collection, retention and sharing of data of people on the move as a core aspect of the implementation of EU migration and border management policies.

Data collection and processing are banal terms today, yet they make all the different to people on the move. Data collected in large databases and their subsequent use by a wide range of authorities have hidden purposes, which cause various harms and are not innocuous. This racist narrative against non EU citizens leads to treating people as suspects in need of constant monitoring, forced to be surveilled at all times. Unsurprisingly, this suspicion and contempt is levelled against marginalised communities especially black and brown people.

One barrier is the complexity and vagueness of the system. There are too many obstacles for people on the move to enforce their data protection rights (e.g., knowledge of the language, the law and the procedures). The consent is the queen of the legal bases, but this is not true with people on the move. The conditions in which people on the move are placed make them more inclined to give their consent to practices that may harm them. The fundamental rights implications are far-reaching for asylum seekers and migrants: their data is used to prevent their arrival, to track their movements, to detain them in closed centres, to deny them entry or visa applications, and much more. Considering the vast power imbalances they face against the EU migration system and the multiplicity of the involved authorities and the complexity of interconnected IT systems, it is harder for them to exercise their fundamental rights, notably their rights to privacy and data protection. So, it’s important that our actions aim to protect people, not data.

Drawing a (red) line in the sand: On bans, risks and the EU AI Act

Session description | Session recording

This panel looked at the EU AI Act, which contemplates a risk-based approach to regulating AI systems, where: (i) AI systems that cause unacceptable risks are banned and prohibited from being placed on the market; (ii) AI systems that cause high risks can be placed on the market subject to mandatory requirements and conformity assessments; and (iii) AI systems that pose limited risks are subject to transparency obligations.

The discussion started about addressing the strategies that civil society could employ to get involved in matters like unacceptable uses of AI. The narrative introduced in the COVID-19 context generated political and social momentum around the idea, that there are good reasons to surrender our privacy and that technology could be used a silver bullet to social problems.

In his analysis of the AI Act Daniel Leufer, from EDRi member Access Now, drew an important conclusion that the risk-based approach of the AI Act must be consistent, with clear criteria and mechanisms that allow the re-evaluation and classification of certain technologies. And added that it is also essential that the AI Act has an extraterritorial effect i.e for companies with a global presence, it is not sufficient to regulate only in one jurisdiction, given that technology can be tested or developed elsewhere.

The discussion also emphasised the need to make use of the political momentum and strike a political commitment by bringing more attention to these issues and ensuring that the AI debate reflects the lived experiences of all communities as no one can claim to be safe from these risks, especially in the face of widespread mass surveillance.

Regulating tech sector transgressions in the EU

Session description | Session recording

The panel discussed the phenomenon of sector transgressions, the idea where firms use their computational infrastructure to find new markets and domains despite not having the required domain expertise to be able to operate in that market, and as a result crowd out existing expertise.

The panel discussed whether transgressions are systemic or symptomatic of other structural issues. Ouejdane Sabbah, a lecturer at the University of Amsterdam, commented that sector transgression technologies have a powerful impact, and we should learn how it affects different social groups. Moving from there, the speakers also examined the linkages between innovation and power and how to build a frame to tackle unaccounted innovation, for instance by demanding transparency in the development and deployment of these projects. There is an inertia of innovation without any democratic input. For example: legitimising the innovation of police cameras as innovative surveillance tools, while the problem is the racist structures and discriminatory power dynamics in the law enforcement institution, not the lack of cameras.

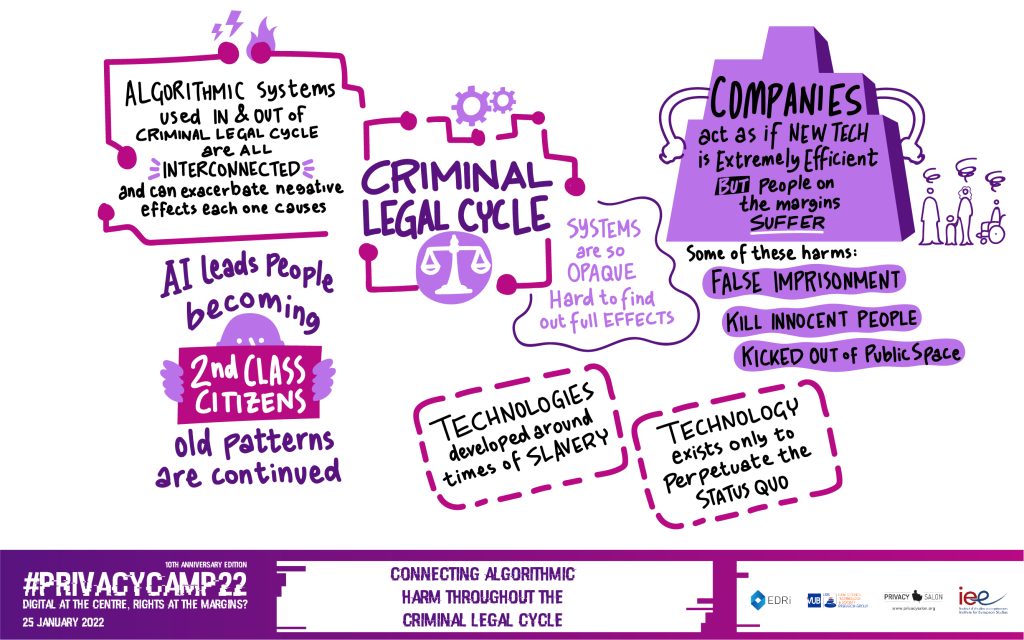

Connecting algorithmic harm throughout the criminal legal cycle

Session description | Session recording

This panel explored how automated decision-making in housing, education, public benefits, and commerce impact the criminal justice cycle and the systemic failures that allow those uses to exacerbate negative impacts and perpetuate societal inequities. The speakers also discussed what this means for advocacy and whether it is even possible to use automated decision-making equitably in this context.

The moderator of the panel Ben Winters, from EPIC, opened the panel, stating that algorithmic systems used throughout both the criminal legal cycle and outside of it are all connected and can exacerbate the negative effects each one causes. For instance, facial recognitions misidentification has led to unfairly kicking out people from ice skating rinks, falsely jailing people, and even accidentally killing innocent people. In this way people are turned into 2nd class citizens. If we look at the historical context, we can see that many of these technologies were developed around the times of slavery.

There is a huge opacity problem with AI decision making. We may know of some problematic systems but it’s very difficult to find out the full impacts because the existence and details of the systems are so opaque. It is often people at the margins who are the most affected by these systems that executives deem efficient and innovative, ignoring the incapability of the people to resist or counter these decisions made about their lives. .

Regulation vs. Governance: Who is marginalised, is “privacy” the right focus, and where do privacy tools clash with platform governance

Session description | Session recording

This panel looked at digital infrastructures reflecting the needs of children and sex workers. The speakers noted that the sole focus on privacy and data protection may not be the most appropriate way to regulate digital platforms and to guarantee a safe environment for users. The discussion focused on different personal, legal, and technological aspects of personal safety, internet governance, and regulatory ideas beyond the General Data Protection Regulation and the Digital Services Act, to work towards new community-driven infrastructures that cater for intersectional justice.

The moderator of the session set the theme of the discussion by questioning the utility of the term “marginalised” when speaking about privacy and security given the diversity of the people affected. For example, the researcher Elissa Redmiles shared some of the findings of her empirical work with sex workers in the EU and US, explaining that it is very difficult for sex workers to protect their safety, privacy and right to work online due to discriminatory platform policies, constant policing of the digital space and lack of privacy tools. Safety in the field would mean many different things to many different people given the diversity to be protected.

The speakers also focused on finding solutions to unjust governance and ineffective regulation, suggesting that platforms should be community-managed and regulation should be shaped from the perspective of freedom of thought as an absolute right to protect communities.

Regulating surveillance ads across the Atlantic

Session description | Session recording

This session aimed to find new avenues of cross-Atlantic cooperation between academia, civil society and decision-makers, in order to increase the impact of surveillance ads regulation in the US and EU – from adoption to enforcement and impact for people. The core of Big Tech’s business model includes extensive tracking and profiling of individuals, including our behavioural history, and using that to micro-target us with ads.

The cost of these large companies’ services is extracting hundreds or thousands of data points (whether you use these platforms or not) and selling the data to the highest bidder. To do that these companies promote content that produces engagement, often the most outrageous content, facilitating and amplifying discrimination, division, delusion. That is why banning surveillance advertising is so important and needed to reclaim our democracy.

Speaking about the future of surveillance ads, Jon von Tetzchner, the CEO of Vivaldi, highlighted that there are positive uses that can be derived from collecting both online and offline data, but collecting information about everything is unacceptable. Tracking people’s every move is the problem. Considering the nature of the metaverse, mass collection of information and spying on each and every user are the real, legitimate risks of the metaverse.

How it started / how it is going: Status of Digital Rights half-way to the next EU elections

Session description | Session recording

Halfway through the current legislative term and the next EU elections, this panel offered a space to reflect on the advancements of digital rights and the challenges we are facing. The session moderator Diego Naranjo, EDRi’s Head of Policy, set the aim of the panel by inviting speakers’ to think about what analytical tools could be useful for civil society organisations to face obstacles on the way and recognise and celebrate successes.

MEP Alexandra Geese provided useful recommendations for civil society, suggesting that rather than commenting on every single amendment, NGOs should focus on building larger alliances and divide labour and efforts based on specialisation. It is important to maintain and strengthen civil society collaboration and coordination and utilise member organisations to influence national governments to change the Council’s positions in trialogues, among others.

Reflecting on how we can make policy more people-focused, Asha Allen from CDT, suggested that in order to ensure that marginalised groups and fundamental rights are respected in EU laws, we need to adopt specific intersectional methods and policies in decision making.

In conclusion, EDRi’s President Anna Fielder added that EDRi can help by articulating what these fundamental rights mean in practice, staying on top of EU policies, identifying digital rights topics to work on, engaging in framing the conversation intentionally and ensuring longer-term investment towards achieving a policy goal and change.

- EDRi: What went down at #PrivacyCamp22? (2022)

- Stop LAPD Spying Coalition and Free Radicals: The Algorithmic Ecology: An Abolitionist Tool for Organizing Against Algorithms (2020)

- Are you being served?: Feminist Server Summit afterlife

- Descontrol in Barcelona: Technological sovereignty Vol.2 (2017)

- EDRi: If AI is the problem, is debiasing the solution? (2021)

- Algoliterary Experiments: Paseo por arboles de Madrid

- Solar Power for Artists

- Vesna Manojlovic: The Internet is for the Empowerment of End Users (2020)

- Big Brother Watch: Poverty Panopticon (2021)

- Who Writes the Rules?

- CEO: How corporate lobbying undermined the EU’s push to ban surveillance ads (2022)

- Transparency International EU: DEEP POCKETS, OPEN DOORS: Big tech lobbying in Brussels (2021)

- Global Data Justice: Resist and Reboot