Retrospective facial recognition surveillance conceals human rights abuses in plain sight

Following the burglary of a French logistics company in 2019, facial recognition technology (FRT) was used on security camera footage of the incident in an attempt to identify the perpetrators. In this case, the FRT system listed two hundred people as potential suspects. From this list, the police singled out ‘Mr H’ and charged him with the theft, despite a lack of physical evidence to connect him to the crime. The judge decided to rely on this notoriously discriminatory technology, sentencing Mr H to 18 months in prison.

Following the burglary of a French logistics company in 2019, facial recognition technology (FRT) was used on security camera footage of the incident in an attempt to identify the perpetrators.

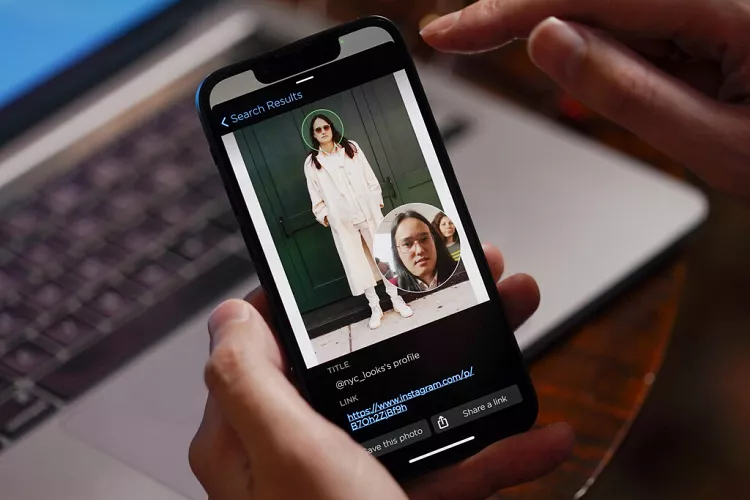

FRT works by attempting to match images from, for example, closed-circuit television (CCTV) cameras to databases of often millions of facial images, in many cases collected without knowledge and consent.

In this case, the FRT system listed two hundred people as potential suspects.

From this list, the police singled out ‘Mr H’ and charged him with the theft, despite a lack of physical evidence to connect him to the crime. At his trial, the court refused a request from Mr H’s lawyer to share information about how the system compiled the list, which was at the heart of the decision to charge Mr H.

The judge decided to rely on this notoriously discriminatory technology, sentencing Mr H to 18 months in prison.

Indicted by facial recognition

“Live” FRT is often the target of (well-earned) criticism, as the technology is used to track and monitor individuals in real time.

However, the use of facial recognition technology retrospectively, after an incident has taken place, is less scrutinised despite being used in cases like Mr H’s.

Retrospective FRT is made easier and more pervasive by the wide availability of security camera footage and the infrastructures already in place for the technique.

Now, as part of negotiations for a new law to regulate artificial intelligence (AI), the AI Act, EU governments are proposing to allow the routine use of retrospective facial recognition against the public at large — by police, local governments and even private companies.

The EU’s proposed AI Act is based on the premise that retrospective FRT is less harmful than its “live” iteration. The EU executive has argued that the risks and harms can be mitigated with the extra time that retrospective processing affords.

This argument is wrong. Not only does the extra time fail to tackle the key issues — the destruction of anonymity and the suppression of rights and freedoms — but it also introduces additional problems.

‘Post’ RBI: The most dangerous surveillance measure you’ve never heard of?

Remote Biometric Identification, or RBI, is an umbrella term for systems like FRT that scan and identify people using their faces — or other body parts — at a distance.

When used retrospectively, the EU’s proposed AI Act refers to it as “Post RBI”. Post RBI means that software could be used to identify people in a feed from public spaces hours, weeks, or even months after it was captured.

For example, running FRT on protesters captured on CCTV cameras positioned. Or, as in the case of Mr H, to run CCTV footage against a government database of a staggering 8 million facial images.

The use of these systems produces a chilling effect in society; on how comfortable we feel attending a protest, seeking healthcare — such as abortion in places where it is criminalised — or speaking with a journalist.

Just knowing that retrospective FRT may be in use could make us afraid of how information about our personal lives could be used against us in the future.

FRT can feed racism, too

Research suggests that the application of FRT disproportionately affects racialised communities. Amnesty International has demonstrated that individuals living in areas at greater risk of racist stop-and-search policing — overwhelmingly affecting people of colour — are likely to be more exposed to more data harvesting and invasive facial recognition technology.

For example, Dwreck Ingram, a Black Lives Matter protest organiser from New York, was harassed by police forces at his apartment for four hours without a warrant or legitimate charge, simply because he had been identified by post RBI following his participation in a Black Lives Matter protest.

Ingram ended up in a long legal battle to have false charges against him dropped after it became clear that the police had used this experimental technology on him. The list goes on. Robert Williams, a resident of Detroit, was falsely arrested for theft committed by someone else.

Randall Reid was sent to jail in Louisiana, a state he’d never visited because the police wrongly identified him as a suspect in a robbery with FRT. For racialised communities, in particular, the normalisation of facial recognition is the normalisation of their perpetual virtual line-up.

If you have an online presence, you’re probably already in FRT databases

This dystopian technology has also been used by football clubs in the Netherlands to scan for banned fans and wrongly issue a fine to a supporter who did not attend the match in question.

Reportedly it has also been used by police in Austria against protesters and in France under the guise of making cities “safer” and more efficient, but in fact, increasing mass surveillance.

These technologies are often offered at low-to-no cost at all.

One company offering such services is Clearview AI. The company has offered highly invasive facial recognition searches to thousands of law enforcement officers and agencies across Europe, the US and other regions.

In Europe, national data protection authorities have taken a strong stance against these practices, with Italian and Greek regulators fining Clearview AI millions of euros for scraping the faces of EU citizens without legal basis.

Swedish regulators fined the national police for unlawfully processing personal data when using Clearview AI to identify individuals.

AI Act could be a chance to end abuse of mass surveillance

Despite these promising moves to protect our human rights from retrospective facial recognition by data protection authorities, EU governments are now seeking to implement these dangerous practices regardless.

Biometric identification experiments in countries across the globe have shown us over and over again that these technologies, and the mass data collection it entails, erode the rights of the most marginalised people, including racialised communities, refugees, migrants and asylum seekers.

European countries have begun to legalise a range of biometric mass surveillance practices, threatening to normalise the use of these intrusive systems across the EU.

This is why, more than ever, we need strong EU regulation that captures all forms of live and retrospective biometric mass surveillance in our communities and at EU borders, including stopping Post RBI in its tracks.

With the AI Act, the EU has a unique opportunity to put an end to rampant abuse facilitated by mass surveillance technologies.

It must set a high standard for human rights safeguards for the use of emerging technologies, especially when these technologies amplify existing inequalities in society.

This article was first published here by euronews.

Contribution by: Ella Jakubowska, Senior Policy Advisor, EDRi, Hajira Maryam, Media Manager & Matt Mahmoudi, AI and Human Rights Researcher, EDRi observer, Amnesty Tech