“Take it personal, and don´t”: changing the decolonising process and letting ourselves be changed

This blog reviews the decolonising process so far and what we've been upto since our last communication, shared in December last year. It adds detail to how we are organising, shifting, and re-orienting the iterative and complex needs of a decolonising process.

The “Decolonising Digital Rights Field in Europe” is a design process to build a decolonising programme for the digital rights field in Europe. 30 participants from the digital rights field and social, economic and racial justice groups are co-designing a programme to address power dynamics in the field and imagine a vision for a decolonial digital future. Our goal is to initiate a process that challenges the structural causes of oppression such as racism, sexism, ableism, homophobia, and transphobia, in order to work towards a digital rights field in which all groups in society have their voices heard and which works to protect the digital rights of all.

This blog reviews the decolonising process so far and what we’ve been upto since our last communication, shared in December last year. It adds detail to how we are organising, shifting, and re-orienting the iterative and complex needs of a decolonising process.

Following the second plenary and the challenges it brought, the Digital Freedom Fund (DFF) and European Digital Rights (EDRi) engaged in a consultation with the participants to readjust the process to their needs. As a result, we shifted the timeline. Now, the process will continue until December 2022, instead of ending in June 2022 as had previously been planned.

Re-orienting the process

In January 2022, we organised two drop-in sessions to discuss new organisational options, we met with trusted experts and had a series of one-to-ones with each participant to discuss what their expectations were, what worked well and what they would like to see change. As process facilitators (the staff at DFF and EDRi organising this process), we also had community of care sessions supervised by an external consultant.

During the consultation, the participants expressed a desire for more spaces in which they could learn about the theory and practice of decolonising, as well as for more shared spaces with the wider group instead of meeting only within their working group constellation (either programmatic, public engagement, partnership- formerly known as collaboration- funding or organisational). They also expressed the wish to prioritise in-person meetings, challenging dominant work practices centring written and online communications, which in many ways mirror colonial dynamics.

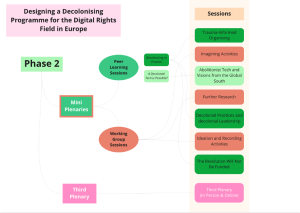

Following the consultations, we planned online peer-learning sessions as well as working group sessions with the aim of both creating a more nurturing environment and building our knowledge about anti-colonial theory and practices. We also began to plan for an in-person plenary to take place at the end of June 2022.

Looking back on the second phase

The peer-learning sessions were divided into two thematic streams: “A decolonial tech is possible?” and “Decolonising as a process”.

The topics of the peer learning sessions were: Trauma-informed organising, Abolitionist tech and visions from the Global South, Anticolonial practices and leadership and one called “The revolution will not be funded”. The title of the last session is a reference to the book of the same name, written by INCITE!. You can find an audio summary of the first two sessions on “Trauma-informed organising” and “Abolitionist tech and visions from the Global South”.

In these sessions, we tried to create a space in which approaching tech through radical anti-oppressive lenses was the new normal. Whether discussing mental health support as a minimum organisational practice, centring the global majority when talking about tech, witnessing the magic of two powerful humans (Anasuya Sengupta and Coumba Touré) from the global South celebrating their mutual friend and dancing as an act of sustainable organising (in the “Anticolonial practices and leadership” session), or discussing philanthropy as the problem and not the solution during the “The revolution will not be funded” session without having to convince the room. We were able to make the space for critical and aspirational ideas, ideas which would ordinarily be de-legitimised or framed as eccentric or unprofessional in other, mainstream spaces. These marginal ideas instead became the central means and reasons to tackle digital injustices. We focused on making space for aspirations, doubts, frustrations, despair, hopes, shortcomings, admiration, experiments and inspirations, and some giggles.

These sessions marked a stark contrast with other spaces in which digital issues are discussed, making clearer how to organise them justly and sustainably. For example, if we agree we need to organise with members of affected communities, we need to completely re-think our compensation models to ensure people representing communities are always paid for their time. They also made apparent what such a recurring space could achieve for the digital rights field in Europe. Finally, the crucial role of funding as a structure irrigated all discussions – often described as the main barrier to sustainable, radical organising.

During the working group sessions, we explored creative writing tools anchored in black and afro-futurism through a session led by Adyam Tesfamarian and video gaming as a reflection on colonial dynamics led by Ahmed Isam Aldin, DFF’s artistic support, who presented his progress on documenting the process or just held space for discussion and research.

The intent of these sessions was to summon creativity and fun as paths to knowledge and regeneration.

The aim of all sessions was to create a space for exchange and transmission with people and organisations who already had experience on a theme relevant to one or multiple working groups. Trying to organise the process as a learning space also requires us to tackle some aspects of value and extractivism inherent to any work relations in our current system. The workplace is often a space in which we expect to know instead of to learn, to give instead of to receive. All this is meant to be fairly compensated by a wage.

This narrative fails to take into account how so many of us are able to learn in the workplace because of the care work of others, in both our personal and professional lives – which liberates extra time and mental space. It concerns domestic work, paid or unpaid, but also emotional support. These dynamics are highly classed, gendered and racialised and intersect with ableism to impact our economic agency. The disability justice movement therefore often invites us to ask whose needs are met, instead of who needs extra care.

We realised that we could not maintain a result-oriented process with the expectation of “designing a multiyear programme” without necessarily making space and resources available to learn and build relevant knowledge. To do otherwise would reproduce these exploitative dynamics.

In-Person Plenary, June 2022

These sessions laid the ground for the in-person plenary meeting during which we tried to implement some of the early learnings of the peer-learning sessions.

The plenary was the first time many of us met physically and spent a prolonged time together. In organising, we as a group had to reckon with the fact that, for some, an in-person event also implies having to deal with the violent visa system, being away from home as care-givers, and the racial, class, gender and disability implications of travelling and crossing borders. The COVID-19 pandemic is not over and some of the participants who were planning on coming were forced to cancel at the last minute due to becoming infected.

In our collective time together, we aimed to connect, enjoy one another, and collaborate toward building the ‘elements’ of our collective decolonising programme. Through working group sessions, collective feedback, and open spaces, we discussed the content of a decolonising programme for the digital rights field.

Sessions such as decolonising as a process, anti- capitalism and technologies, identity politics and collective liberation, reparations and healing, decolonising evaluation frameworks, accountability in an anticolonial organisation, exploring funding dynamics and envisioning alternative models. The open sessions concluded with an exercise of mapping what decolonising means to us, as a way of bringing together many of the ideas from the open sessions.

Intentional spaces for creativity, connection and emotion

In planning for the plenary, we were intentional to create as much spaciousness as possible, conscious that the topics required it. This meant that each session was optional, and that we didn´t go full speed on the first day. We deliberately integrated time for connection and spaces of joy, for people to meet and talk and do things together before having to enter what we knew would often be difficult conversations. Inviting artistic practices and fun into the planning and as core activities also helped to ease us into our time together. We held a collaborative painting exercise, went swimming, were dancing, had an open-mic session, and even imagined together anti-colonial t-shirt slogans.

These sessions created the basis for all of us to get to know each other and begin to build trust. It also made this plenary feel like a needed and restful break for many, who arrived exhausted from professional and personal lives in which they have to juggle between many crises and expectations. One participant said, “it’s nice how you organised this retreat, we are doing a lot and it still feels really relaxed and fun.”

Anti-colonial practices penetrated how we were together in the space. During a tour of the host property (located in the Piemonte region of northern Italy), we discovered that Napoleon had previously visited the property, and a Ginkgo tree had subsequently been planted there in his ‘honour’. We reflected on what it means to commemorate a figure playing a central colonial role as reinstater of slavery in France through violent wars in the West Indies, using torture, massacre and legal codes, and leader of several colonial enterprises in India and on the African continent in a race against the English monarchy. In response, Ahmed Isam Aldin decided to organise a collective artistic intervention on the last day to exorcise Napoleon’s spirit.

During the ceremony Ahmed gathered us around the tree. Some of us chanted, others purified the tree with water, thanking it for carrying the colonial pain, manufactured objects were thrown, we read texts and cast liberation spells or stayed silent. One of the participants said, “this tree was very far away from many of our ancestors, although it symbolises so much of the violence they had to resist against for us to be here, and here we are, facing it, we are getting closer and closer”. The power of this moment is hard to describe. It lifted our spirits and helped us digest and transform some of the sentiments that travelled through us during the day and probably had been stuck here for a long time.

Iteration as a decolonising practice

The plenary was a clear example of why the process of the design phase is as important as the outcomes, and that leaving space for imagination and the non-tangible allows the group to take a step away from the productivity modes into a mindset of the ambitious vision of decolonisation.

The spacious nature of the decolonising process allows for iterative work to happen. Collectively designing the elements of the programme often leads to reassessing what the problem is, which leads to re-evaluating what the goal is, feeding into the work on the elements, and so on. As such, the process is resisting linear trajectories, we often have the feeling of coming back to topics already discussed but it is frequently either more in-depth, from a different angle, or with a new perspective. It feels messy at times, or stagnant, or both. But looking back to where we started a year ago, we are in a very different place.

The plenary offered a space to connect. Many stated how this meeting differed from the work events they usually attend, because of the spaciousness and care built in, the people in the room as well as the topics tackled. The different meeting spaces were renamed after anti-colonial leaders, for instance, we had the Amilcar Cabral courtyard and the Bibi Titi Mohamed working room. They became meeting points. Another participant shared with us “This was the first meeting in a long time where I felt like I didn’t have to spend energy on push back on matters of anti-racism, marginalisation or decolonising”. During this very short time, small things hinted towards the desirable future we wish to participate in – leaving us hopeful. It also made it harder to return to “business as usual”.

The plenary left a lingering feeling of something precious; a sense of community, safety, solidarity, rest (and fatigue), of sharing a common purpose despite our differences. There was a lot of joy, jokes, laughter, there were tears, some yelling, a non-negligible amount of discomfort as well as people supporting each other. We left feeling simultaneously exhausted and emotional, feelings heightened by the news that the general right to safe abortion had been repealed in the United States. Most could feel the magic of what happens during in-person meetings: sensing personal and group energies, sharing emotions, conducive thought processes, connection with our bodies, and space to reflect.

What’s coming next?

We are entering the final phase of the process of designing a multiyear decolonising programme for the digital rights field. The next steps will be to close some gaps in our reflections and consult broader communities and different locations, to assemble a programme.

The working groups will now enter a phase of refinement and triage: exploring which element should come first, how can we make our plans more concrete, what type of organisation should be in charge of the implementation etc. As process facilitators, DFF and EDRi will support them in this work by organising further peer learning sessions, as well as a collaborative working session during which they will be invited to map the gaps.

Finally, we are planning to hold a plenary in early December to allow the different working groups to finalise their ideas and bring them together into a coherent programme. This plenary will be held in person, provided that the pandemic allows for it.

As process facilitators, we are immensely grateful for the commitment, engagement, patience, creativity and resilience of the core participants and advisory group. We also want to thank Nati and Esra from The Hum for their support and facilitation throughout the process.

We can’t wait to see what the programme will look like.

For updates on the decolonising process, follow @df_fund and @edri on Twitter!

This blog was drafted by Laurence Meyer, Digital Freedom Fund and Sarah Chander, EDRi