The EU AI Act and fundamental rights: Updates on the political process

The negotiations of the EU’s Artificial Intelligence Act (AIA) are finally taking shape. With lead negotiators named, the publication of Council compromises, and the formation of civil society coalitions on the AIA, 2022 will be an important year for the regulation of AI systems.

The EU AI act political process

After the release of the European Commission’s proposal on Artificial Intelligence in April 2021, there was a long process of analysis, critique and political manoeuvring.

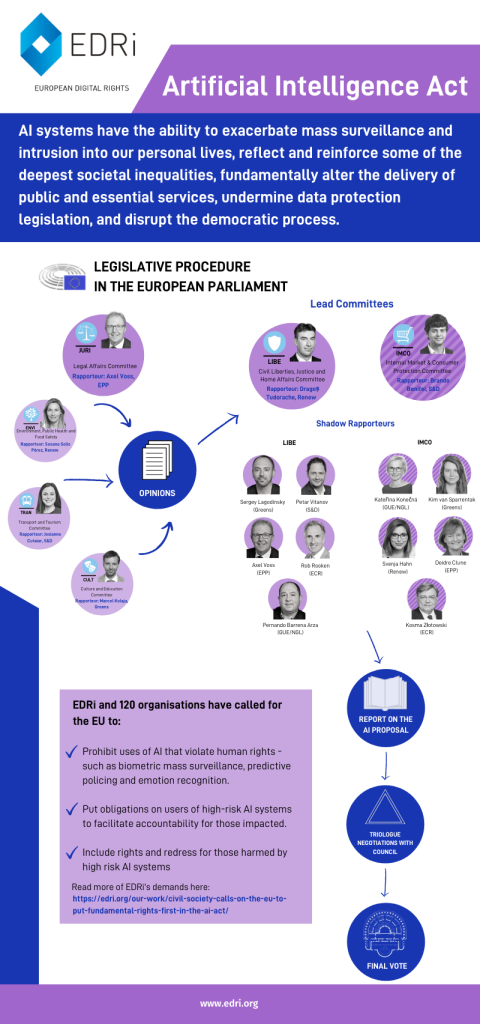

Whilst civil society were quick to call for structural improvements to the AI act, the European Parliament engaged in a long competence battle to decide which MEPs and committees lead the negotiations. The result was announced in late 2021, and the negotiations will be led jointly by the Internal Market (IMCO) and the Civil Liberties (LIBE) committees, with a role for the Legal Affairs (JURI) Committee, including exclusive competence on transparency issues, human oversight and codes of conduct.

To expand the infographic, click on it once.

In the Council, substantive work is taking place, with compromise texts published by the Slovenian and the French Presidencies, putting forward changes to the Commission’s proposal. Exploring the Council’s proposed amendments so far, the following themes emerge:

Enabling AI-based surveillance

One concerning trend is the increasing loopholes in the text for the uses of AI in the context of national security. In November 2021 the Slovenian presidency proposed that AI systems ‘exclusively developed or used for national security purposes’ should be excluded from the scope of the legislation. In addition, the same text failed to remove the wide exemptions to the use of remote biometric identification in publicly accessible spaces (despite the significant public momentum for a full prohibition), and removed some forms of law enforcement data analysis from the list of ‘high-risk’ applications.

Later, the French presidency added yet another worrying national security loophole, namely that in a ‘duly justified situation of urgency for exceptional reasons of public security’ law enforcement bodies may put a ‘high risk’ AI system into service without the authorisation of national enforcement bodies (if law enforcement makes the necessary authorisation later).

These proposals are likely to pose a number of threats to fundamental rights, including risks of disproportionate surveillance, potentially discriminatory applications and consequences for democracy and rule of law, if there are systematic loopholes for uses of otherwise ‘high-risk’ AI systems when used by the state. These changes are to be seen within a wider context of the use of data-driven practices for national security, law enforcement and migration control contexts, often vastly disregarding concerns for fundamental rights and the impact on racialised and criminalised groups.

Small shifts for fundamental rights

Meanwhile, the Council texts contain some, albeit limited, useful amendments to ensure the AI Act implements safeguards for fundamental rights. As called for by EDRi, the Slovenian text widens the prohibition on social scoring to include private actors, and removes vague and unhelpful references to ‘general purposes’ and also to scoring based on ‘trustworthiness. It is, however, still to be seen whether this prohibition is drafted appropriately to address the numerous algorithmic systems still having harmful and discriminatory impacts on people, including in social welfare provision.

There remain a number of open questions when it comes to the Council’s positions. It is still yet to be said if the Council will consider requiring fundamental rights impact assessments of AI systems, nor implementing rights and redress mechanisms for people affected by AI systems.

Further, when it comes to the question of enforcement and governance of the Act, the Council has yet to take a strong stance. There have been some indications that Member States have objected to the strong role the European Commission provides itself in the act. However, in the Slovenian text, there were only minimal steps to address this, including more references to the advisory role of the European AI board. Further, the Slovenian text proposed that the update of the list of high risk uses (Annex III) should only occur every 2 years, as opposed to the 1 year initially proposed.

What is civil society calling for?

Understanding that the use of AI can impact a wide range of communities and human rights, we have been organising our work on the AI Act closely with other civil society organisations, including Algorithm Watch, the International Platform for Undocumented Migrants (PICUM), Fair Trials and the European Disability Forum.

The majority of this work has been coordinated within EDRi’s ‘AI core group’, with members Access Now, Bits of Freedom, ECNL, epicenter.works and Panoptykon Foundation taking a leading role.

In November 2021, 123 civil society organisations launched a Political Statement on the EU Artificial Intelligence Act setting out our main recommendations for legislators. Since then, we’ve been collaboratively developing amendments.

The amendments mainly relate to the following three themes:

This would include ensuring the list of ‘prohibited practices’ is wide enough to include all systems which pose an unacceptable risk for fundamental rights, including a full ban on remote biometric identification in publicly accessible spaces, biometric categorisation, emotion recognition (except for legitimate health uses), predictive policing, and invasive and discriminatory uses in the migration context.

Further, the AIA needs a meaningful way to update the risk-based system to include AI systems that are developed in the future that may also pose a ‘high’ or ‘unacceptable’ risk.

The AIA needs a meaningful mechanism to ensure foresight, transparency and accountability to those affected by the use of high-risk AI. Currently the Act focuses on highly technical, self-assessed checks by AI providers, but does little to oblige the ‘users’ of high risk AI to assess and document the potential impact of these systems in the context of their use. There must be an obligation on users to conduct and publish a fundamental rights impact assessment before using high-risk AI, and to register uses on the public database already in the AIA.

In order to be useful for people affected or even harmed by high-risk AI systems, the act needs to develop a framework of how to empower people. The AIA should confer individual rights to people impacted by AI systems (including the right to an explanation and the right not to be subject to prohibited AI), and also introduce ways for them to enforce their rights, including the right to complain to a national body and to seek a remedy for infringements.

EDRi will continue to work toward these goals in the upcoming negotiations, focusing on how the AI act can be a vehicle for people’s fundamental rights and social justice.

(Contribution by:)

Read more

-

EU’s AI law needs major changes to prevent discrimination and mass surveillance

The European Commission has just launched the its proposed regulation on artificial intelligence (AI). As governments and companies continue to use AI in ways that lead to discrimination...

-

EDRi submits response to the European Commission AI adoption consultation

Today, 3rd of August 2021, European Digital Rights (EDRi) submitted its response to the European Commission’s adoption consultation on the Artificial Intelligence Act (AIA).

-

Civil society calls on the EU to put fundamental rights first in the AI Act

Today, 30 November 2021, European Digital Rights (EDRi) and 119 civil society organisations launched a collective statement to call for an Artificial Intelligence Act (AIA) which foregrounds fundamental...