This is the EU’s chance to stop racism in artificial intelligence

Human rights mustn’t come second in the race to innovate, they should rather define innovations that better humanity. The European Commission's upcoming proposal may be the last opportunity to prevent harmful uses of AI-powered technologies, many of which are already marginalising Europe's racialised communities.

The European Commission’s upcoming proposal may be the last opportunity to prevent harmful uses of AI-powered technologies, many of which are already marginalising Europe’s racialised communities, writes Sarah Chander

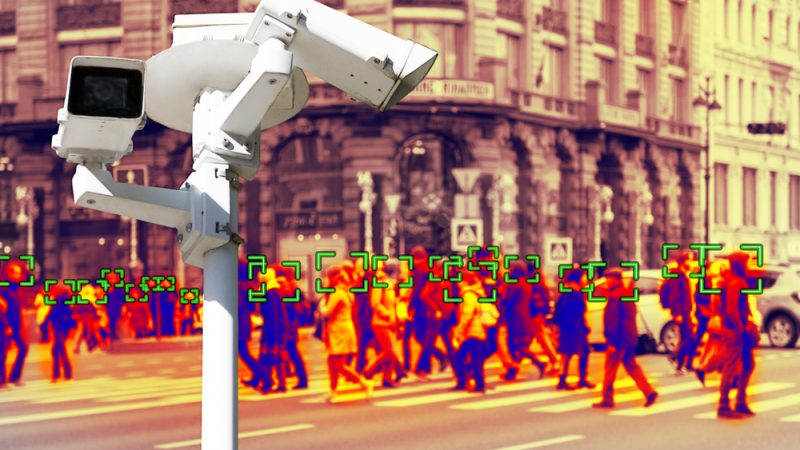

Whether it’s police brutality, the disproportionate over-exposure of racial minorities to COVID-19 or persistent discrimination in the labour market, Europe is “waking up” to structural racism. Amid the hardships of the pandemic and the environmental crisis, new technological threats are arising. One challenge will be to contest the ways emerging technologies, like Artificial Intelligence (AI), reinforce existing forms of discrimination. From predictive policing systems that disproportionately score racialised communities with a higher ”risk” of future criminality, all the way to the deployment of facial recognition technologies that consistently mis-identify people of colour, we see how so called “neutral” technologies are secretly harming marginalised communities.

The use of data-driven systems to surveil us and to provide a logic to discrimination is not novel. The use of biometric data collection systems such as fingerprinting have their origins in colonial systems of control. The use of biometric markers to experiment, discriminate and exterminate was also a feature of the Nazi regime. To this day in the EU, we have seen a number of similar, worrying practices, including the use of pseudo-scientific ‘lie detection’ technology piloted on migrants in the course of the visa application process. This is just one example where governments, institutions and companies are extracting data from people in extremely precarious situations. Many of the most harmful AI applications rely on large datasets of biometric data as a basis for identification, decision making and predictions.

What is new in Europe, however, is that such undemocratic projects could be legitimised by a policy agenda “promoting the uptake of artificial intelligence” in all areas of public life. The EU policy debate on AI, while recognising some ‘risks’ associated with the technology, has overwhelmingly focused on the purported widespread “benefits” of AI. If this means shying away from clear legal limits in the name of promoting “innovation”, Europe’s people of colour will be the first to pay the price. Soon, MEPs will need to take a position on the European Commission’s legislative proposal on AI. While EU leaders such as Executive Vice-President Vestager and Vice President Jourová have each spoken on the need to ensure AI systems do not amplify racism, the Commission has been under pressure from tech companies like Google to avoid “over-regulation”.

Yet, the true test of whether innovations are worthwhile is how far they make peoples’ lives better. When industry claims human rights safeguards will “hinder innovation”, they are creating a false distinction between technological and social progress. Considerations of profit should not be used to justify discriminatory or other harmful technologies. Human rights mustn’t come second in the race to innovate, they should rather define innovations that better humanity. A key test will be how far the EU’s proposal recognises this.

As the European Commission looks to balance the aims of ‘promoting innovation’ and ensuring technology is ‘trustworthy’ and ‘human-centric’, it may suggest a number of limited regulatory techniques. The first is to impose protections and safeguards only for the most “high-risk” of AI applications. This would mean that, despite the unpredictable and ever-changing nature of machine learning systems, only a minority of systems would actually be subject to regulation, despite the harms being far more widespread. The second technique would be to take limited actions requiring technical “de-biasing”, such as making datasets more representative. However, such approaches rarely prevent discriminatory outcomes of AI systems. Until we address the underlying causes of why data encodes systemic racism, these solutions will not work.

Both of these proposals would provide insufficient protection from systems that are already having vastly negative impact on human rights, in particular to those of us already over-surveilled, and discriminated-against. What these “solutions” fail to address is that, in a world of deeply embedded discrimination, certain technologies will, by definition, reproduce broader patterns of racism. There is no ‘quick fix’ no risk assessment sophisticated enough, to undo centuries of systemic racism and discrimination. The problem is not just baked into the technology, but into the systems in which we live. In most cases, data-driven systems will only make discrimination harder to pin down and contest.

Digital, human rights and anti-racist organisations have been clear that more structural solutions are needed. One major step put forward by the pan-European ‘Reclaim Your Face’ campaign is an outright ban on destructive biometric mass surveillance technologies. The campaign, coordinated by European Digital Rights (EDRi), includes 45 organisations calling for a permanent end to technologies such as facial, gait, emotion, ear canal recognition that target and disproportionally oppress racialised communities.

The Reclaim Your Face European Citizens’ Initiative petition aims to collect 1 million signatures to call for a Europe-wide ban and promote a future without surveillance, discrimination and criminalisation based on how we look or where we are from. Beyond facial recognition, EDRi, along with 61 other human rights organisations have called on the European Union to include “red-lines” or legal limits on the most harmful technologies – in its laws on artificial intelligence, especially those that deepen structural discrimination. The upcoming AI regulation is the perfect opportunity to do this.

AI may present significant benefits to our societies, but these benefits must be for us all. We cannot accept technologies that only benefit those who sell and deploy them. This is especially valid in areas rife with discrimination. Some decisions are too important and too dangerous to be made by an algorithm. This is the EU’s opportunity to make people a priority and stop discriminatory AI before it’s too late.

The op-ed was first published by the Parliament Magazine here.

Contribution by: