Why EU passenger surveillance fails its purpose

The EU Directive imposing the collection of flyers’ information (Passenger Name Record, PNR) was adopted in April 2016, the same day as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). The collection of PNR data from all flights going in and out of Brussels has a strong impact on the right of privacy of individuals and it needs to be justified on the basis of necessity and proportionality, and only if it meets objectives of general interest. All of this lacks in the current EU PNR Directive, which is at the moment being implemented in the EU.

The Austrian implementation of the PNR Directive

In Austria, the Austrian Passenger Information Unit (PIU) has processed PNR since March 2019. On 9 July 2019, the Passenger Data central office (Fluggastdatenzentralstelle) issued a response to inquiries into PNR implementation in Austria. According to the document, from February 2019 to 14 May, 7 633 867 records had been transmitted to the PIU. On average, about 490 hits per day are reported, with an average of about 3 430 hits per week requiring further verification. According to the document, out of the 7 633 867 reported records, there were 51 confirmed matches and in 30 cases there was the intervention by staff at the airport concerned.

Impact on innocents

What this small show of success does not capture, however, is the damage inflicted on the thousands of innocent passengers who are wrongly flagged by the system and who can be subjected to damaging police investigations or denied entry into destination countries without proper cause. Mass surveillance that seeks a small, select population is invasive, inefficient, and counter to fundamental rights. It subjects the majority of people to extreme security measures that are not only ineffective at catching terrorists and criminals, but that undermine privacy rights and can cause immense personal damage.

Why is this happening? The rate fallacy

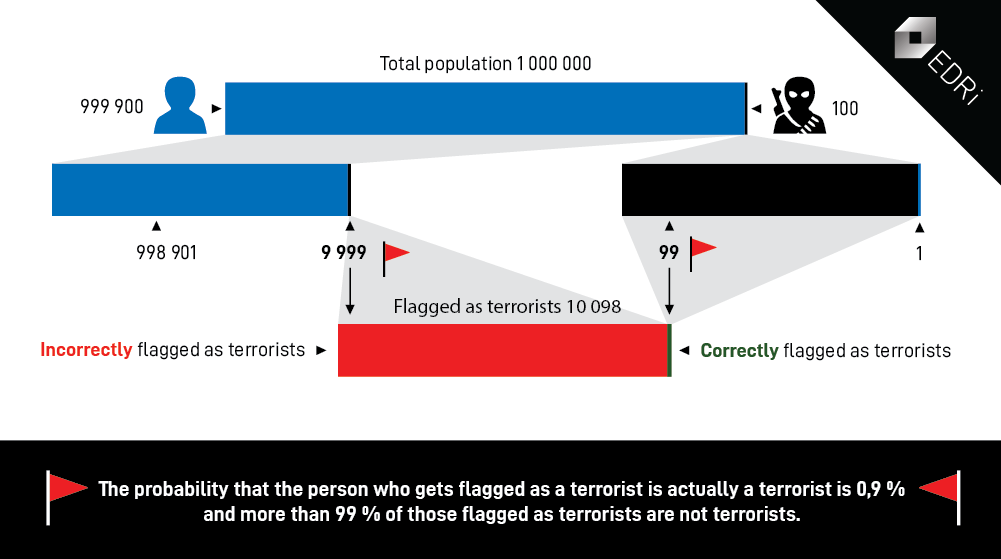

Imagine a city with a population of 1 000 000 people implements surveillance measures to catch terrorists. This particular surveillance system has a failure rate of 1%, meaning that (1) when a terrorist is detected, the system will register it as a hit 99% of the time, and fail to do so 1% of the time and (2) that when a non-terrorist is detected, the system will not flag them 99% of the time, but register the person as a hit 1% of the time. What is the probability that a person flagged by this system is actually a terrorist?

At first, it might look like there is a 99% chance of that person being a terrorist. Given the system’s failure rate of 1%, this prediction seems to make sense. However, this is an example of incorrect intuitive reasoning because it fails to take into account the error rate of hit detection.

This is based on the rate fallacy: The base rate fallacy is the tendency to ignore base rates – actual probabilities – in the presence of specific, individuating information. Rather than integrating general information and statistics with information about an individual case, the mind tends to ignore the former and focus on the latter. One type of base rate fallacy is the one we suggested above called the false positive paradox, in which false positive tests are more probable than true positive tests. This result occurs when the population overall has a low incidence of a given condition and the true incidence rate of the condition is lower than the false positive rate. Deconstructing the false positive paradox shows that the true chance of this person being a terrorist is closer to 1% than to 99%.

In our example, out of one million inhabitants, there would be 999 900 law-abiding citizens and 100 terrorists. The number of true positives registered by the city’s surveillance numbers 99, with the number of false positives at 9 999 – a number that would overwhelm even the best system. In all, 10 098 people total – 9 999 non-terrorists and 99 actual terrorists – will trigger the system. This means that, due to the high number of false positives, the probability that the system registers a terrorist is not 99% but rather is below 1%. Searching in large data sets for few suspects means that only a small number of hits will ever be genuine. This is a persistent mathematical problem that cannot be avoided, even with improved accuracy.

Security and privacy are not incompatible – rather there is a necessary balance that must be determined by a society. The PNR system, by relying on faulty mathematical assumptions, ensures that neither security nor privacy are protected.

Epicenter.works

https://en.epicenter.works/

PNR – Passenger Name Record

https://en.epicenter.works/thema/pnr-0

Passenger surveillance brought before courts in Germany and Austria (22.05.2019)

https://edri.org/passenger-surveillance-brought-before-courts-in-germany-and-austria/

We’re going to overturn the PNR directive (14.05.2019)

https://en.epicenter.works/content/were-going-to-overturn-the-pnr-directive-0

NoPNR – We are taking legal action against the mass processing of passenger data!

https://nopnr.eu/en/home/

An Explainer on the Base Rate Fallacy and PNR (22.07.2019)

https://en.epicenter.works/content/an-explainer-on-the-base-rate-fallacy-and-pnr

(Contribution by Kaitlin McDermott, EDRi-member Epicenter.works, Austria)