Hakuna Metadata – Let’s have some fun with Sid’s browsing history!

But I am not interesting enough for someone to bother to look into my browsing history.

The most common argument for people not to be more wary of the threats to their online privacy is that, simply, no one cares. Or at least not enough. But still, don’t we all like to delete our browsing history from time to time, at least to prevent details about some of our searches being exposed unintentionally? Maybe we would care more if we knew just how many surprising insights can be gleaned from our online activity.

We are aware that when surfing online we give out information about all of our searches and all the websites that we visit. Furthermore, everything we do – click on buttons, move our mouse pointer, type something, scroll up or down – will be tracked through little monsters called “cookies”. All together this information composes your “browsing history”, which is the metadata of your browsing activity. As EDRi member SHARE Foundation showed by diving into one person’s browsing history, we can follow a person through the day and learn about his or her interests, passions, worries – almost as it is seen through that person’s eyes.

This seems scary, perhaps even enough to change our online behaviour a little. However, we imagine that we have control over our browsing history through our computer. We also trust our browser not to abuse the information about our searches. But there are also other interested parties. For example, your Internet Service Provider (ISP), who can access your metadata, has almost full access to your browsing history. Interested in what they can learn about you?

EDRi’s Ford-Mozilla Open Web Fellow Sid Rao built an open source browsing history visualisation tool, which can show you what exactly is it that you give away and how.

So, let’s imagine Sid is connected to the internet through his Internet Service Provider (ISP) – let’s call it “Telekome”. What does Telekome know about Sid, relying on the metadata from his browsing (or simply his browsing history), without ever asking for his consent?

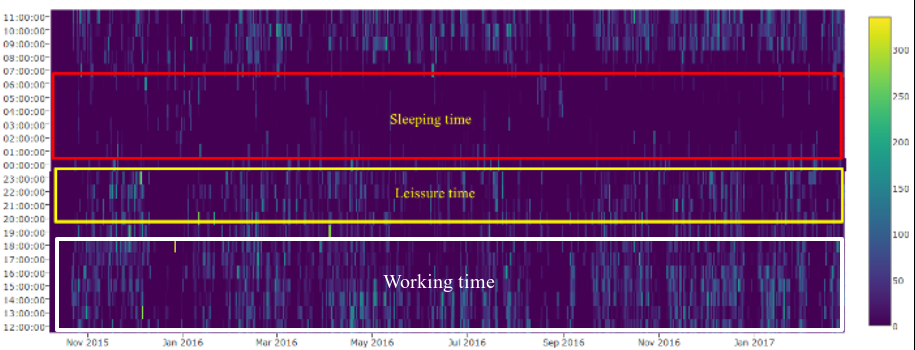

Like most of us, Sid is a creature of habit. That means it is quite easy to learn about his usual everyday routines from his browsing patterns. Sid uses the same laptop both for his work and personal activities, which is a common practice these days. However, the ways he uses the internet during his working and leisure hours are very different.

A simple “heatmap” of his browsing actions gives a snapshot of his lifestyle. In this heatmap, colours are assigned to his browsing history: lightest shade to the time when he has visited the biggest number of unique websites, and darkest when the number decreases. As the graph shows, his sleeping time has darkest patches, meaning that during those hours, he hasn’t been browsing much. His leisure time has light coloured patches – showing that during those times he probably watches online videos, but does not systematically spend all this time online. Finally, the most cluttered part of heatmap with a lot of light coloured patches is his work hours, which he typically spends mainly online, visiting many websites.

With adding up other metadata, such as the suffix of the domain name of the browsed websites, which generally correlate to a specific country, Telekome can easily learn that he travelled to a different time zone, but continued working on his usual hours.

Anomalies (in this case, the strange patches of different shades of colour in irregular places) in the pattern could mean different things: Has Sid’s workload increased? Is he planning a trip? Searching for a job? In this case, we see how browsing activity indicates the holidays Sid took. This depicts that he planned his holidays by checking flights, confirming hotel booking, and so on, and took a break from work. He then returned home, where a sudden increase of activity is possibly due to following up on work activities. Finally, he resumed to his usual work pattern.

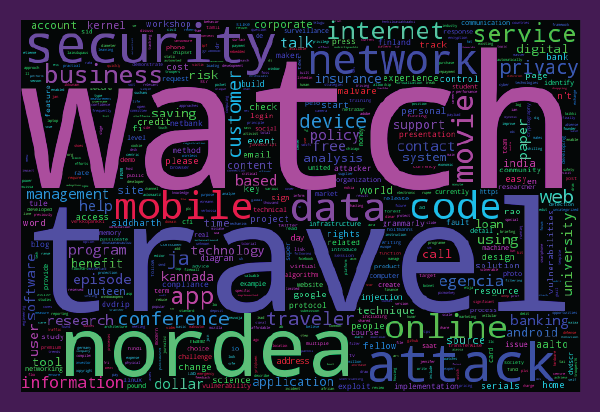

By now, Telekome knows about Sid’s schedule, but what about his interests? On the basis of keywords, metadata can reveal quite a lot about people, organisations and locations that Sid is interested in. Sid is a security and privacy researcher, so vocabulary related to his work stands out, but also other keywords related to his identity – both from professional and personal life.

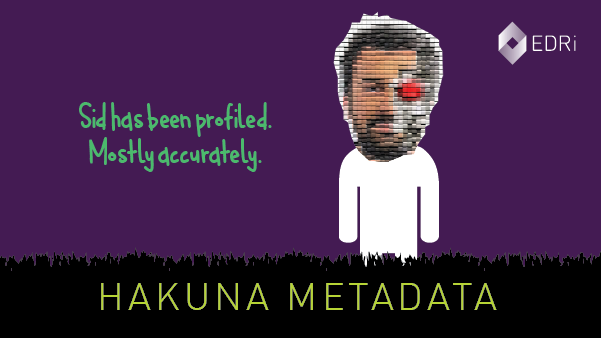

We see that Telekome already knows quite a lot about Sid. Is he a potential customer for insurance companies and travel agencies, or a candidate for management related jobs? What could his next travel destination be? Who are the people he is interested in? But hey, this information doesn’t seem to be very harmful after all! Why should he be worried?

He should be worried because the legislation does not adequately protect users’ metadata. It can easily be used by advertisers, data brokers, or even political campaigns. They can then target Sid, according to these data, and adding to it what they already previously knew about him. It might change his consumer behaviour and turn it into profit, or it might as well change how he votes in the next elections!

Wait, there is more! Because of the nature of Sid’s work, some suspicious words, such as “attack” and “security”, turn up frequently. Combined with the fact that he travels often to various destinations, assumptions about his racial profile, and all the other information that can be accessed through his browsing metadata, he might end up on a watchlist of a government agency. Sid’s browsing pattern suddenly changes, he is browsing more than usual, he goes to the airport, and out of nowhere, the authorities do not let him onboard a plane. Something that he planned as relaxing holidays turns into a nightmare.

Metadata can easily be processed with the use of algorithms, which extract our behavioural patterns and profile us. However, metadata can never give the whole picture of who we are. Assumptions have to be made to compensate for the missing pieces of the puzzle – and they can be wrong.

You can also read this article in German at https://netzpolitik.org/2017/hakuna-metadata-warum-metadaten-und-browserverlaeufe-mehr-ueber-uns-verraten-als-oft-vermutet/.

What does your browsing history say about you? (22.02.2017)

https://edri.org/what-does-your-browsing-history-say-about-you/

SHARE Lab: Browsing Histories – Metadata Explorations

https://labs.rs/en/browsing-histories/

EDRi: Hakuna Metadata – Exploring the browsing history (22.03.2017)

https://edri.org/hakuna-metadata-exploring-the-browsing-history/

Hakuna Metadata (1) – Exploring the browsing history

http://www.privacypies.org/blog/metadata/2017/02/28/hakuna-metadata-1.html

Video: Metadata Explained

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xP_e56DsymA

(Contribution by Zarja Protner, EDRi intern, and Siddharth Rao, Ford-Mozilla Open Web Fellow, EDRi)