Hey Google, where does the path lead?

If you do not know the directions to a certain place, you use a digital device to find your way. With our noses glued to the screen, we blindly follow the instructions of Google Maps, or its competitor. But do you know which way you are being led?

Mobility is a social issue

Mobility is an ongoing debate in the Netherlands. Amsterdam is at a loss on how to deal with the large cars on the narrow canals, and smaller municipalities such as Hoogeveen is constructing a beltway to offset the Hollandscheveld area. Governors want to direct the traffic on the roads and as a result, they deliberately send us either right or left.

If all is well, all societal interest are weighed in on that decision. If one finds that the fragile village center should be offset, the road signs in the berm direct the drivers around it. If the local authorities want to prevent cars from rushing past an elementary school, the cars are being routed through a different path.

Being led by commercial interests

However, we are not only being led by societal interests. More and more, we use navigation systems to move from place A to place B. Those systems are being developed by an increasingly smaller group of companies, of which Google seems to be the frontrunner. Nowadays, hardly anyone navigates using a map and the traffic signs on the side of the road. We only listen to the instructions from the computer on the dashboard.

In this way, a commercial enterprise determines which route we take – and it has other interests than the local authorities. It wants to service its customers in the best possible way. But who are these customers? For some companies, that’s the road users, but for others – often those where the navigation is free for the users – the customers that really matter are the invisible advertisers.

Too much of a short cut

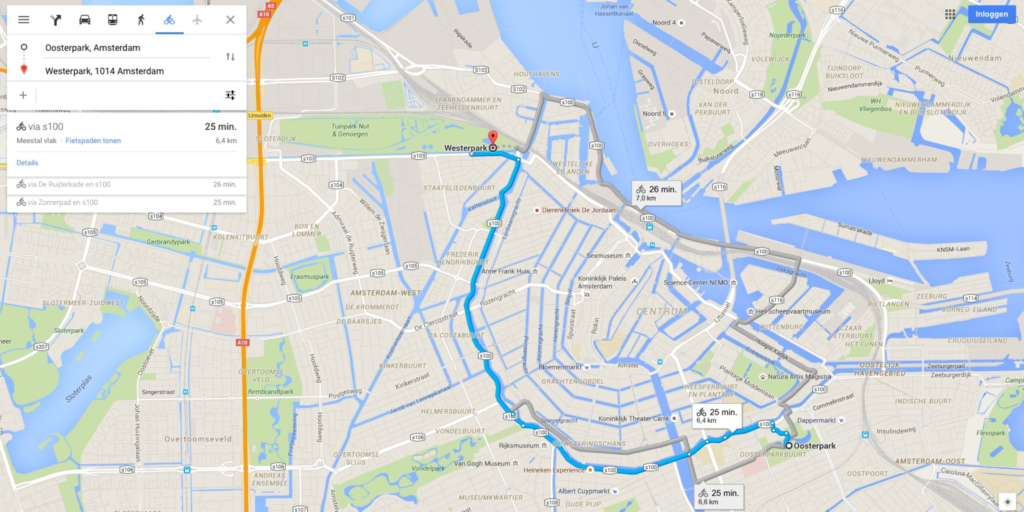

And even that is too limited of course. Because which consideration the developer of the navigation system really takes is rarely transparent. When asking Google for a route from the Westerpark to the Oosterpark in Amsterdam, it leads you around the canal belt, instead of through it. That doesn’t seem to be the shortest route for someone on a bicycle.

Why would that be? Maybe Google’s algorithm is optimised for the straight street patterns of San Francisco and it’s unable to work with the erratic nature of the Amsterdam canals. Maybe it’s the fastest route available. Or maybe it’s a very conscious design choice so that the step-by-step description of the route does not become too long. Another possibility is that the residents of the canal belt are sick of the daily flood of cycling tourists and have asked Google, or maybe paid for it, to keep the tourists out of the canal belt. We simply don’t know.

Being misled

Incidentally, the latter-mentioned reason is less far-fetched than you would think at first. When you are in Los Angeles, you can’t miss the letters of the Hollywood Sign. A lot of tourists want to take a picture with it. Those living on the hill underneath the monumental letters are sick of it. They have, sometimes illegally, placed signs on the side of the road that state that the huge letters are not accessible through their street.

With the rise of digital maps that action became less and less successful. Pressurised by a municipal councillor, Google and Garmin, a tech company specialising in GPS technology, adjusted their maps so that tourists are not being led to the actual letters, but to a vantage point with a view of the letters. Both mapmakers changed their service under pressure of an effectively lobbied councillor.

Serving a different interest

It’s very rarely transparent which interests companies are taking into consideration. We don’t know which decisions those companies take and on which underlying data and rules they are based. We don’t know by whom they are being influenced. We can easily assume that the interests of such companies are not always compatible with public interests. This has a major impact on the local situation. If a company like Google listens to retailers, but not residents, the latter will be disadvantaged. The number of cars in and around the shopping streets is growing – which sucks, if you happen to live there. And even more so, if the local authorities do try to route the cars differently.

Again, this is another good example of how the designer of a technology impacts the freedom of the user of the technology. It also impacts society as a whole: we lose the autonomy to shape our living environment with a locally elected administration.

Moreover, this story is not only about the calculated route, but also about the entire interface of the software. The Belgian scientist Tias Guns described that very aptly: “There is, for example, an option to avoid highways, but an option to avoid local roads is not included.” As a driver, try and spare the local neighbourhood then.

The platform as a “dead end”

Adding to that – ironically – is that the major platforms are not always reachable. Where do you have to turn to if you want Google Maps to route less traffic through your street? Or, actually more, if you are a retailer? On a local level, this is different. There is a counter at the city hall where you can go, and there is a city council where you can put traffic problems on the agenda. This, by itself, is already very difficult to coordinate. The Chief Technology Officer of the city Amsterdam recently told in an interview about the use of artificial intelligence in the local authority:

“In some areas, residents have a larger capability to complain. Think of the city centre or the ‘Oud-Zuid’ area both more affluent areas and home to a large number of lawyers. It’s general knowledge that in those areas a complaint is made far easier than, for example, the less affluent area of Amsterdam “Noord”. This is not difficult for trained operators. They can handle experienced grumblers, and can judge for themselves whether the complaint is valid. A computer can not.”

Another issue is that some digital mapmakers are so large – and will continue to grow – that they can afford to listen selectively.

Who determines the path?

So, who decides how our public space is being used? Is that a local city council or a commercial enterprise? This makes quite a difference. In the first case, citizens can participate, decisions are made democratically, and there is a certain amount of transparency. In the second case, you have no information on why you were led left or right, or why shopping streets have become desolate overnight. Most likely the rule is: whoever pays, gets to decide. The growing power of commercial enterprises in the issue of mobility is threatening to put local administrations – and with that us, the citizens and small companies – out of play.

Bits of Freedom

https://www.bitsoffreedom.nl/

Hey Google, which way are we being led? (15.05.2019)

https://www.bitsoffreedom.nl/2019/05/15/hey-google-which-way-we-being-led/

Hey Google, which way are we being led? (in Dutch, 15.05.2019)

https://www.bitsoffreedom.nl/2019/04/15/hey-google-waarheen-leidt-de-weg/

Why people keep trying to erase the Hollywood sign from Google Maps (21.11.2014)

https://gizmodo.com/why-people-keep-trying-to-erase-the-hollywood-sign-from-1658084644

(Contribution by Rejo Zenger, EDRi member Bits of Freedom, the Netherlands; translation from Dutch to English by Bits of Freedom volunteers Alex Leering and Amber Balhuizen)