Interoperability: A way to escape toxic online environments

The political debate on the future Digital Services Act mostly revolves around the question of online hate speech and how to best counter it. Whether based on state intervention or self-regulatory efforts, the solutions to address this legitimate public policy objective will be manifold. In its letter to France criticising the draft legislation on hateful content, the European Commission itself acknowledged that simply pushing companies to remove excessive amounts of content is undesirable and that the use of automatic filters is ineffective in front of such a complex issue. Out of the range of solutions that could help to tackle online hate speech and foster spaces for free expression, a legislative requirement for certain market-dominant actors to be interoperable with their competitors would be an effective measure.

Trapped in walled gardens

Originally, the internet enabled everyone to interact with one another thanks to a series of standardised protocols. It allowed everyone to share knowledge, to help each other and be visible online. Because the internet infrastructure is open, anyone can create their own platform or means of communication and connect with others. However, the internet landscape dramatically changed in the last decade: the rise of Big Tech companies has resulted in a highly centralised online ecosystem around few dominant players.

Their power lies in their huge profits stemming from an opaque advertisement business and in the enormous user bases that drag even more users into their services. Unlike the historical openness of the internet, these companies strive for even higher profits by closing their systems and locking their customers in. Hence, the costs to leave are too high for many to actually take the leap. This gives companies an absolute control over all the interactions taking place and the content posted on their services.

Facebook, Twitter, YouTube or LinkedIn decide for you what you should see next, track each action you make to profile you and decide whether your post hurts their commercial interests, and therefore should be removed, or not. In that context, you have no say in the making of the rules.

Unhealthy communications

What is most profitable for those companies is content that generates the most profiling data possible – arising from each user interaction. In that regard, pushing offensive, polarising and shocking content is the best strategy to capture users’ attention and trigger a reaction from them. Combining this with a system of rewards – likes, views, thumbs up – for the ones using the same rhetorical strategies, these companies provide a fertile ground for conflict and the spread of hate. In this toxic environment based on arbitrary decisions, this business model explains how death threats against women can thrive while LGBTQIA+ people are censored when discussing queer issues. Entire communities of users are dependent on the goodwill of the intermediaries and must endure sudden changes of “community guidelines” without any possibility to contest them.

When reflecting on the dissemination mechanisms of hate speech and violent content online, it is easy to understand that delegating the task to protect victims to these very same companies is absolutely counter-intuitive. However, national governments and the EU institutions have mainly chosen this regulatory path.

Where is the emergency exit?

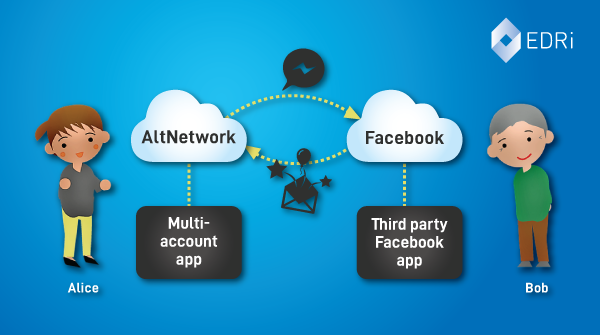

Another way would be to support the development of platforms with various commercial practices, degrees of user protection and content regulation standards. Such a diversified online ecosystem would give users a genuine choice of alternative spaces that fit their needs and even allow them to create their own with chosen community rules. The key to this system’s success would be to maintain the link with the other social media platforms, where most of their friends and families still remain. Interoperability would guarantee to everyone the possibility to leave without losing their social connections and to join another network where spreading hate is not as lucrative. On the one hand, interoperability can help escape the overrepresentation of hateful content and dictatorial moderation rules, while on the other hand, it triggers the creation of human-scaled, open but safe spaces of expression.

The way it works allows a user on service A to interact with, read and show content to users on a service B. This is technically well feasible: For example, Facebook used to build its messaging service on an open protocol before 2015 and Twitter still permits users to tweet directly from third-party websites. It is crucial that this discussion takes place in the wider debate around the Digital Services Act: the questions of who decides how we consume daily news, how we connect with friends online and how we choose our functionalities should not be left to a couple of dominant companies.

Content regulation – what’s the (online) harm? (09.10.2019)

https://edri.org/content-regulation-whats-the-online-harm/

France’s law on hate speech gets a thumbs down

https://edri.org/frances-law-on-hate-speech-gets-thumbs-down

Hate speech online: Lessons for protecting free expression (29.10.2019)

https://edri.org/hate-speech-online-lessons-for-protecting-free-expression/

E-Commerce review: Opening Pandora’s box? (20.06.2019)

https://edri.org/e-commerce-review-1-pandoras-box/

(Contribution by Chloé Berthélémy, EDRi)