Wiretapping children’s private communications: Four sets of fundamental rights problems for children (and everyone else)

On 27 July 2020, the European Commission published a Communication on an EU strategy for a more effective fight against child sexual abuse material (CSAM). As a long-term proposal is expected to be released by this summer, we review some of the fundamental rights issues posed by the initiatives that push for the scan of all private communications.

“We have regulation already that it is mandatory, to detect fraud towards copyright issues, so I think if we can protect copyright issues, we can also protect children.” (Commissioner Johansson)

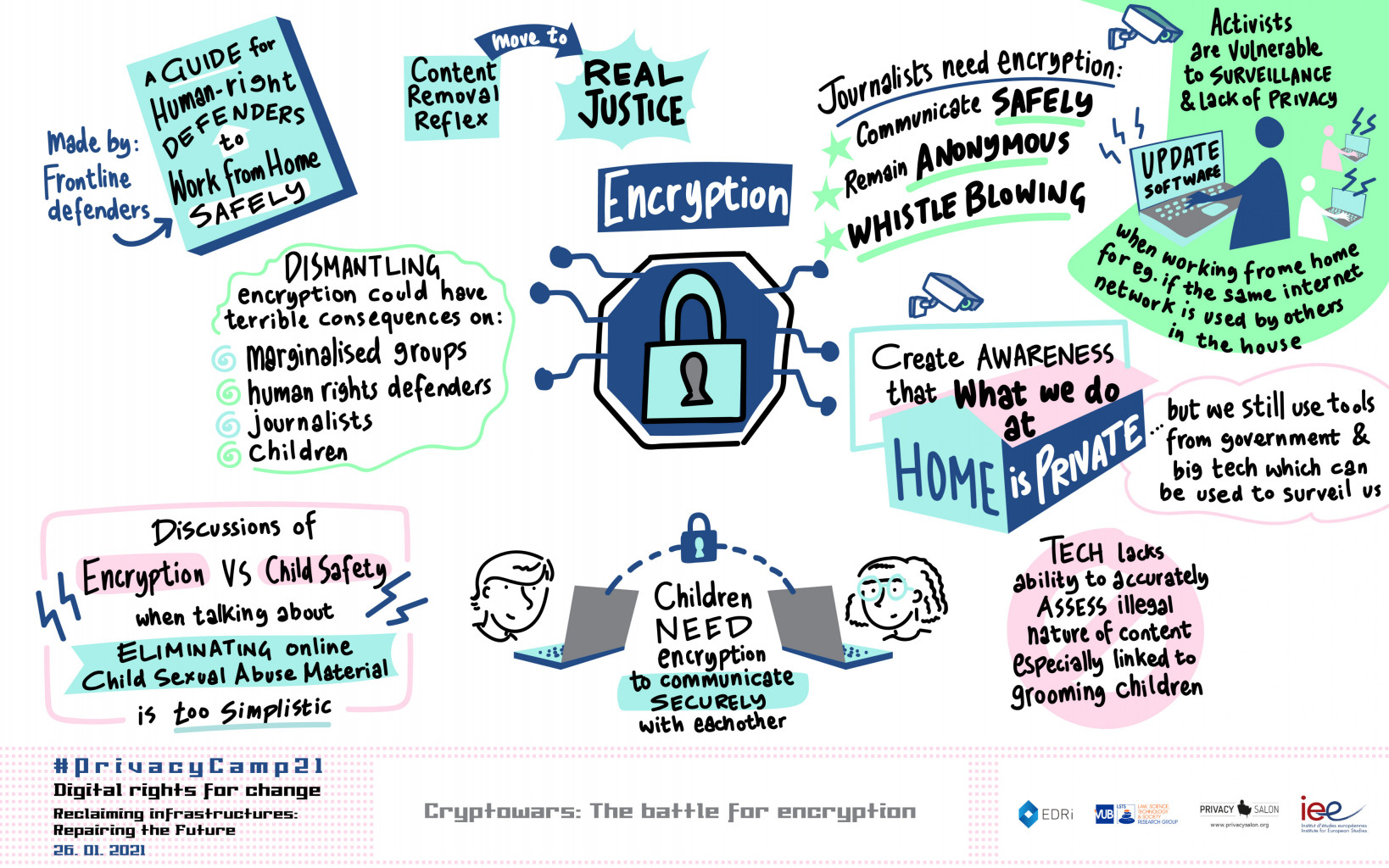

Right in the middle of summer (when controversial legislations are often proposed) the European Commission published a proposal for a temporary legislation that would legalise the continuation of scanning of private communications. A long-term proposal is expected by this summer. The interim proposal, which raised concerns from the start of Cryptowars 3.0, was fuelled (behind the scenes) by the same person who has been proposing the use of technology (PhotoDNA) to detect “terrorist” content in the Terrorist Content Online (TCO) Regulation.

After the text was proposed by the Commission, there was an attempt to get it adopted in a rush without sufficient parliamentary discussions. Because of this “slow” process, the European Parliament Child Rights Intergroup said that without this legislation the EU would become a “safe haven for peadophiles.” A bit exaggerated, you might think, until you read similar claims in The Guardian, the New York Times and Fortune mixing encryption and scanning of private communications with riots and child abuse. Posing scanning of private communications as a dilemma between child protection and privacy is a false dichotomy, as children too require privacy in their daily lives.

In order to give a bit of the necessary background, here are four fundamental rights issues that are posed by the initiatives that push for the scan of all private communications.

1- Lack of clarity of services covered, legal basis and legality of current practices

Even though EDRi has been asking for months, it is not entirely clear which specific services, platforms, applications and technologies are being referred to by “technologies for the processing of personal and other data” to detect Child Sex Abuse Material (CSAM) in the CSAM interim Regulation. It is not clear either under which legal basis (if any) the companies that offer services, platforms, applications and technologies are currently performing these practices. Furthermore, the scope became increasingly large with the news saying that dating apps and videoconferencing tools could come under the scope of this initiative. To make things worse, the Commission has even refused to reply to the question of whether the current practices they want to continue are even legal under EU law.

2- Criticism from EDPS, the European Parliament and UNICEF

The European Data Protection Supervisor’s (EDPS) Opinion on the Commission proposal concluded that the legislative should not be adopted in its original form as it did not meet the criteria of necessity and proportionality, and in particular because of the lack of a specific legal basis and lack of clear and precise rules governing the scope and application of the measures in question as well as the lack of adequate safeguards.

Equally, the European Parliamentary Research Service (EPRS) has just issued a report on this topic saying that “instead of using these techniques to monitor all private messages, their use should be limited to private messages of persons already under suspicion of soliciting child abuse or distributing CSAM” (page 47) and that current practices may be sending data to countries with an inadequate level of protection (p. 44 of the report).

Last but not least, UNICEF is not too happy about these mass scanning practices either. A toolkit on Children’s Online Privacy and Freedom of Expression published by UNICEF on scanning tools said that improving privacy and data protection for children is essential for their development and for their future as adults. The toolkit highlights that any monitoring tools should “bear in mind children’s growing autonomy to exercise their expression and information rights”.

3- Normalisation of scanning of communications and the slippery slope of surveillance

Despite the voices from the European Commission saying that the debates on the interim Regulation were not about attacking encryption and confidentiality of communications, these proposals to allow the scanning of private communications align with the broader narrative to prevent encryption from being deployed widely.

The rhetoric being peddled by the European Commission leading to the imposition of upload filters in the Copyright Directive and in the Terrorist Content Online Regulation (aka TERREG) is worrisome. As with other types of content scanning (whether on platforms like YouTube or in private communications) scanning everything from everyone all the time creates huge risks of leading to mass surveillance by failing the necessity and proportionality test. Furthermore, it creates a slippery slope where we start scanning for less harmful cases (copyright) and then we move on to harder issues (child sexual abuse, terrorism) and before you realise what happened scanning everything all the time becomes the new normal.

This normalisation of treating everyone as guilty until proven innocent needs to be stopped. Each of these proposals should first and foremost carry out a proper impact assessment, evaluate which practices are the least invasive ones to achieve the alleged aims, etc… Rushed technological ‘solutions’ rarely (if ever) work for the intended purpose, and can create unintended consequences for everyone else.

4- Empowerment of big tech companies

We cannot allow big tech to become even more powerful. Allowing and encouraging Facebook and other companies to continue scanning private communications would put private companies in charge of surveillance and censorship mechanisms that, because of their impact on fundamental rights, should be the responsibility of public authorities. While the EU is on one hand trying to restrict the power of Big Tech in the Digital Services Act (DSA), Digital Markets Act (DMA), the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) these initiatives that allow Big Tech to police private communications only reinforce their power as gatekeepers and as key allies of governments for the surveillance of the population. Whose best interest are these technosolutionist proposals for, if not primarily that of Big Tech overflowing pockets?

What are the alternatives?

The problems that are suggested (private communications are a risk for X and Y) and the alleged solutions for those problems (using upload filters, scanning private communications) need to be proven before undertaking initiatives that could have a chilling effect on our privacy. In the debates on scanning all children’s communication, there is a lack of, at least, the following information and actions:

- Low-hanging fruit: The Commission has the power to ensure the enforcement of the to-do list that Civil Liberties Committee of the European Parliament (LIBE) proposed back in 2017 in the Report on the implementation of Directive 2011/93/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 December 2011 on combating the sexual abuse and sexual exploitation of children and child pornography

- In order to assess the urgency and necessity, Europol and national law enforcement authorities should provide specific information about the increase of abuses and of spread of CSAM online during 2020 in Europe. So far the data provided was about the increase of reporting, not an increase of individual pieces of content or individuals affected

- In order to assess the proportionality and efficiency of the measures proposed: The Commission and EU Member States need to provide concrete and thorough information about the number of prosecutions and convictions in the US and in the EU as of result of existing ‘voluntary’ practices

- In order to assess the legality of existing practices: The Member of the European Parliament Birgit Sippel (S&D group, Germany) said in her draft Report on the interim Regulation that the European Commission did not wish “to take a stance on whether current voluntary practices to detect and report child sexual abuse material are in fact legal under EU law”. It is reckless to push for the urgent continuation of ‘voluntary’ practices (voluntarily pushed by Member States) without even being sure that the measures are legal. A review by data protection authorities of the legality of existing “voluntary” practices under existing legislation (legal basis, data protection impact assessment, etc…) is clearly needed

- The illegality of current ‘voluntary’ scanning practices has already been exposed by the EPRS report cited above. The impact of scanning private communications on journalists, whistle blowers and children need to be further explored

- If the use of hashing technologies is considered legal in some cases, any future initiative that uses hash databases to detect illegal material must be pursued within a strong rule-of-law framework that includes safeguards for fundamental rights; this would include ensuring that any such database operates with open source software, is controlled by public independent institutions, and operates under full public scrutiny (including regular third party audits) rather than relying on US technologies and databases handled by private US organisations as it is currently the case

(Contribution by:)

- Facebook’s encryption plans could help child abusers escape justice, NCA warns (The Guardian)

- EPRS Report

- EDPS Opinion on the Proposal for temporary derogationsfrom Directive for the purpose of combating child sexual abuse online

- Open Letter: Civil society views on defending privacy while preventing criminal acts

- Is surveilling children really protecting them? Our concerns on the interim CSAM regulation (EDRi)