Missing: people’s rights in the EU Digital Decade

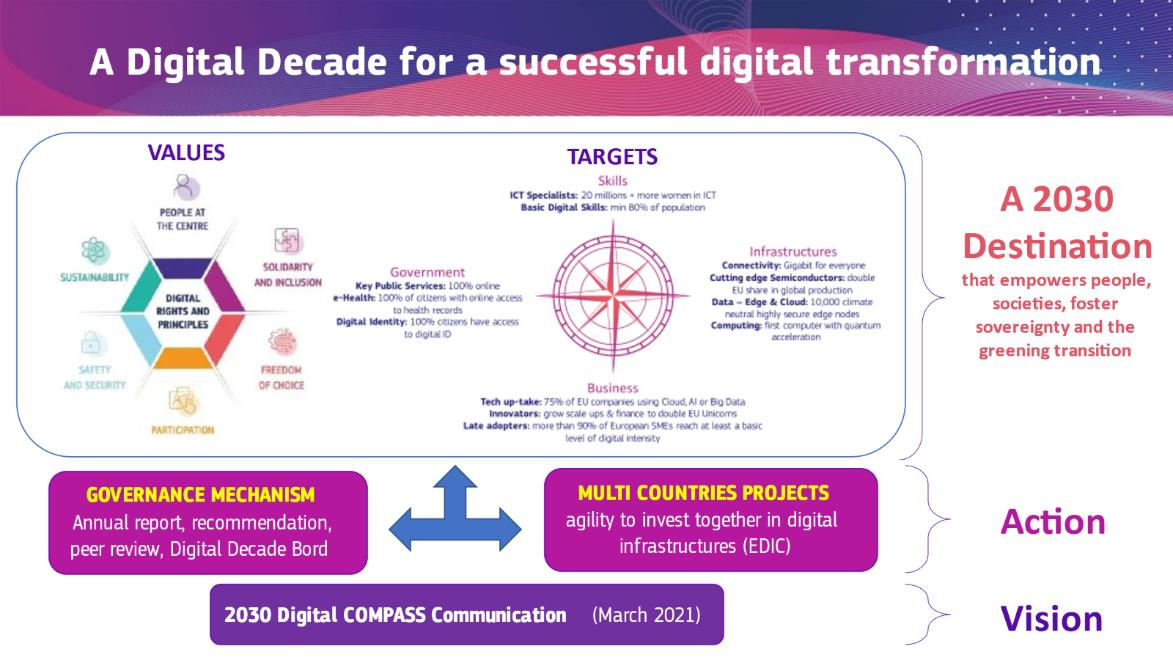

In June 2023, the European Union (EU) will adopt its first report on the state of the ‘Digital Decade’ – a plan launched in 2022 with digitalisation targets for business, public services and people’s digital skills. The Digital Decade reads more like a business plan than a policy programme.

The plan’s ethos is the uptake of artificial intelligence (AI), 6G, clouds, web3 and other digital hypes, sending a ‘wake up call’ message to Member States to surf the ‘new wave of the digital revolution’. The ‘societal challenges’, or harms on people, are considered as an afterthought. This is also true for the Decade Policy governance model, in which industry is over-represented and civil society is almost absent.

The Digital Decade annual assembly and reports are supposed to be the ‘yearly rendezvous‘ (meeting) to take stock of digital policies”. Without deliberate efforts to centre people and include civil society organisations, it will be a ‘rendezvous manqué’ (missed opportunity).

In 2022, the EU adopted its Digital Decade policy programme with targets for the digitalisation of public services:

- 100% of key public services to be accessible online

- 80% of citizens to have access to digital ID

- 75% of EU companies to use Cloud/AI/Big Data

- 80% of the population to gain basic digital skills

The Declaration of Rights and Principles was plugged in to guide the digital transformation and complement the digitalisation targets. Yet it is not clear how ‘rights and values’ will be part of the focus of the actors involved, or of the annual reporting cycle.

The space and access that the industry has been given to shape the process reflect how central market and economic interests are to the EU digitalisation. These ‘soft law’ lobbying efforts contribute to shaping the EU agenda on digital technologies in a way that tends to weaken actual ‘hard law’ negotiated by the EU co-legislators and undermine protection mechanisms for people.

Instead of market growth and profit, the EU’s approach to digitisation should address its effects on privacy, dignity, accessibility – and the growing inequality and injustice affecting marginalised groups, bearing the brunt of technological harms, extractive dynamics and the invisible labour/resources necessary for the digital transformation.

Alternative to Big Tech’s business models

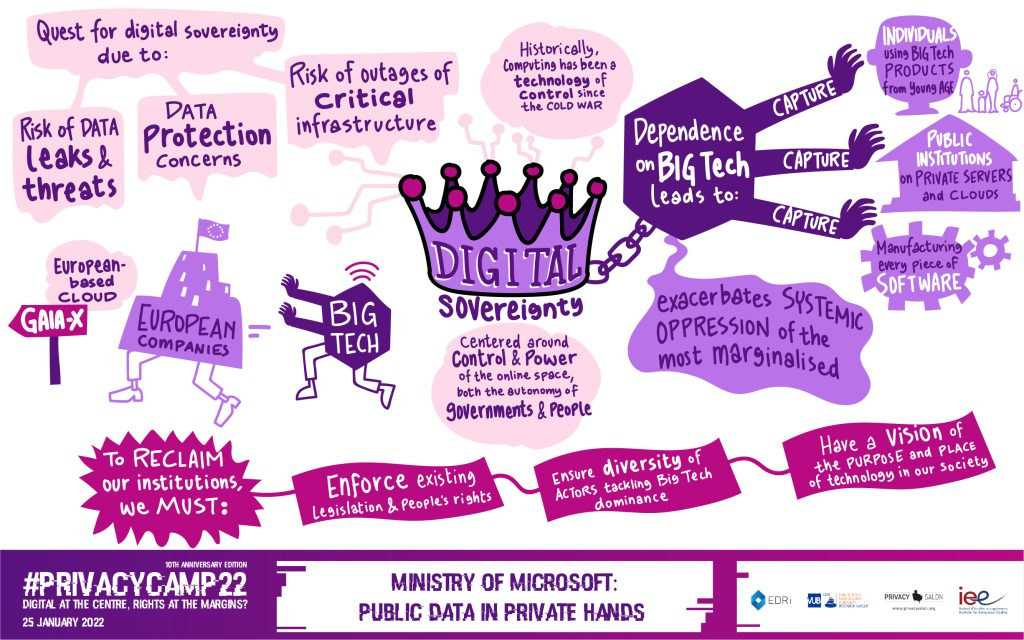

At the preparation workshop on the State of the European report, industry representatives did not hide their plans to develop European GAFAMs. The European technology industry is eager to claim digital sovereignty to its advantage: to create European infrastructure through initiatives such as Gaia-X, for European-based clouds. But this is bound to fail as Big Tech has a data advantage, and a computing power advantage. In 2021, non-European service providers host 80% of European data.

Big Tech’s dominance doesn’t stop at clouds. An overall trend is the growth strategy of Big Tech in Europe into public domains like healthcare, education, public services and public administration.

Regardless of whether the technology being deployed is European, American or Chinese-owned, for it to be truly centred on social values and people’s interests it must prioritise data protection and fundamental rights. Therefore, we need to see investing in decentralised community-led platforms, and free and open-source software, as part of our common internet infrastructure. The point is not to simply replicate Big Tech’s infrastructure, but to have a real vision for the use and role of technology in our societies. Especially when boasted by EU and public money, technology should lead to public benefits.

Empowerment of people and accountability of digitalisation agents

There is an inherent digital exclusion resulting from the digitalisation of most public services. ‘Digital-by-default’ format puts an extra burden on those who already face exclusion and could result in people losing their autonomy or their rights. The EDRi network has raised such concerns with the eIDAS regulation, which foresees the eID being used for a huge range of services by 2030. In Czechia, EDRi member IuRe has led a ‘right to analogue’ campaign to voice the need to access public service offline.

Centring people in technology development and deployment means that people’s lives should not be used as tech testing grounds. Evidence has shown that it is often marginalised groups in our societies that are heavily harmed by these tech experiments.

EDRi along with other civil society organisations have been warning about some of the most harmful tech uses already happening in Europe: monitoring and identifying people in public spaces, predicting the likelihood of criminality, and making crucial decisions about people that determine access to welfare, education and employment.

In the AI Act negotiations, EDRi and a civil society coalition have been pushing for the empowerment of people affected by AI systems, accountability for institutions using AI systems and the prohibition of AI uses creating high risks for people’s fundamental rights.

Misleading tech solutions to the climate crises

The digital decade is presented as a key enabler of the green transition. However, the ‘twinning of the digital and the green transitions’ creates a misleading image of the ability of technology to solve the climate crisis. Conversely, there is growing evidence of the adverse impact of technology on the climate and the environment.

Instead of developing a false narrative that technology is the ultimate solution to climate crisis, we need to adopt sufficiency models, transform our way of living, and recognise the continuum between colonial exploitation of the past and the current extractive practices.

In the context of a closing civic space for NGOs, the European Commission must limit industry access to influence EU digital policies and meaningfully engage with civil society organisations defending people’s rights and the planet.