Competition law: Big Tech mergers, a dominance tool

This is the third article in a series dealing with competition law and Big Tech. The aim of the series is to look at what competition law has achieved when it comes to protecting our digital rights, where it has failed to deliver on its promises, and how to remedy this.

This is the third article in a series dealing with competition law and Big Tech. The aim of the series is to look at what competition law has achieved when it comes to protecting our digital rights, where it has failed to deliver on its promises, and how to remedy this. Read the first article on the impact of competition law on your digital rights here and the second article on what to do against Big tech’s abuse here.

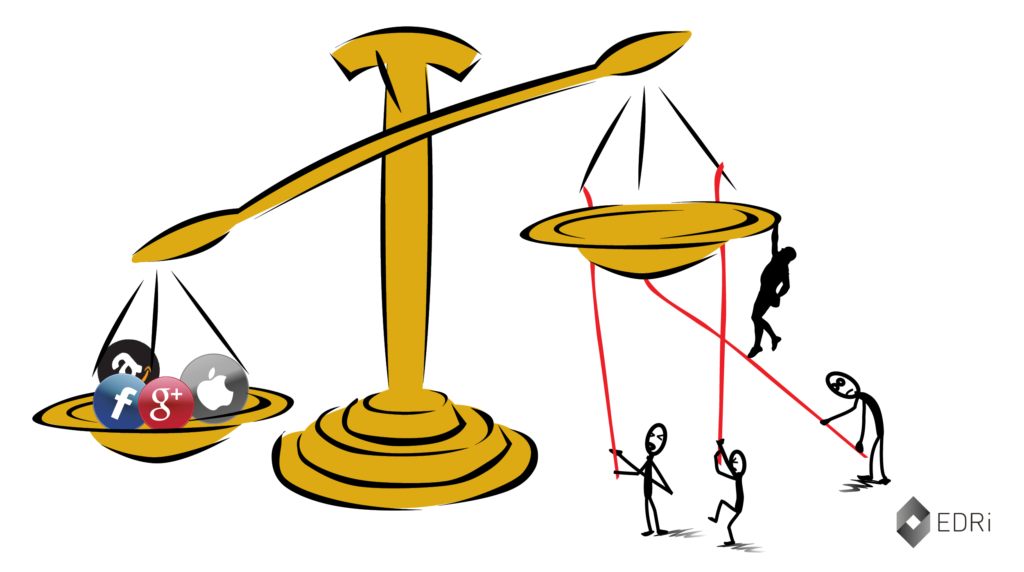

One way Big Tech has been able to achieve a dominant position in our online life, is through mergers and acquisitions. In recent years, the five biggest tech companies (Amazon, Apple, Alphabet – parent company of Google, Facebook and Microsoft) spent billions to strengthen their position in acquisitions that shaped our digital environment. Notorious acquisitions which made headlines include: Facebook/WhatsApp, Facebook/Instagram, Microsoft/LinkedIn, Google/YouTube, and more recently, Amazon/Twitch.

Beyond infamous social media platforms and big deals, Big Tech companies also acquire less known-companies and start-ups, which also greatly contribute to their growth. While not making big newsworthy acquisitions, Apple still “buys a company every two to three weeks on average” according to its CEO. Since 2001, Google-Alphabet has been acquiring over 250 companies and since 2007, while Facebook acquired over 90. Big Tech’s intensive acquisition policy particularly applies to artificial intelligence (AI) startups. This is worrying because reducing competitors also means reducing diversity, leaving Big Tech in charge of developing these technologies, at a time where AI technologies are more and more used in decisions affecting individuals and are known to be susceptible to bias.

Big Tech’s intensive acquisition policy can have different goals at play, sometimes at the same time. These companies acquire competitors who could have offered, or were offering consumers, an alternative, in order to eliminate or shelve them (“killer acquisitions”), in order to consolidate a position in the same market or in a neighbouring market, or in order to acquire their technical or human skills (“talent acquisitions”).

See for example this overview of Google and Facebook’s acquisitions.

And in time of economic trouble, Big Tech is even more lurking. In the US, Senator Warren wants to introduce a moratorium on COVID-era acquisitions.

Big Tech’s mergers are mostly unregulated

While mergers and acquisitions are part of business life, the issue is that most Big Tech’s acquisitions

are not subject to any control.

And the few ones which are reviewed have been authorised without conditions. This led to debates on the state of competition law: are the current rules fit for today’s age of data-driven acquisitions and technology takeovers?

While some already called for a ban on acquisitions by certain companies, others are discussing the thresholds set in competition law to allow review by competent authorities, but also, more intrinsically, the criteria used to review mergers.

The issue with thresholds is that they depend on monetary turnover, which many companies and startups do not reach, either because they haven’t yet monetised their innovations or because their value is not reflected in their turnover but, for example, in their data trove. Despite low turnovers, Facebook was still willing to spent 1 and 19 billions for, respectively, Instagram and WhatsApp. These data-driven mergers allowed for these companies’ data sets to be aggregated, increasing the (market) power of Facebook.

The French competition authority suggests for example, to introduce an obligation to inform the EU and/or national competition authorities of all the mergers implemented in the EU by “structuring” companies. These “structuring” companies would be defined clearly according to objective criteria and in cases of risks, the authorities would ask these players to notify the mergers for review.

However, although the acquisition of WhatsApp by Facebook was reviewed by the European Commission thanks to a referee from national competition authorities, the operation was still authorised.

This poses another issue: the place of data protection and privacy in merger control. Competition authorities assume that, since there is a data protection framework, data protection rights are respected and individuals are exercising their rights and choices. But this assumption does not take into account the reality of the power imbalance between users and Big Tech. In this regard, some academics, such as Orla Lynskey suggests solutions such as the increased cooperation between competition, consumers and data protection authorities to understand and examine the actual barriers to consumer choice in data-driven markets. Moreover, where it is found that consumers value data privacy as a dimension of quality, the competitive assessment should therefore reflect whether a given operation would deteriorate such quality.

A wind of change might already be coming from the US, as the Federal Trade Commission issued last February “Special Orders” to the five Big Tech companies, “requiring them to provide information about prior acquisitions not reported to the antitrust agencies”, including how acquired data has been treated.

Google/Fitbit: the quest for our sensitive data

The debate recently resurfaced when Google’s proposed acquisition of Fitbit was announced. Immediately, a number of concerns were raised, both in terms of competition and of privacy (see for example the European Consumer Organisation BEUC, and the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF)’s concerns). From a fundamental rights perspective, the most worrying issue lies in the fact that Google would be acquiring Fitbit’s health data. As Privacy International warns, “a combination of Google / Alphabet’s potentially extensive and growing databases, user profiles and dominant tracking capabilities with Fitbit’s uniquely sensitive health data could have pervasive effects on individuals’ privacy, dignity and equal treatment across their online and offline existence in future.”

Such concerns are also shared beyond civil society, as the announcement led the European Data Protection Board to issue a statement, warning that “the possible further combination and accumulation of sensitive personal data regarding people in Europe by a major tech company could entail a high level of risk to the fundamental rights to privacy and to the protection of personal data.”

It is a fact that Google cannot be trusted with our personal data. As well as a long history of competition and data protection infringements, Google is questionably trying to enter the healthcare market, and already breaking patients’ trust.

Beyond concerns, this operation will be the opportunity for the European Commission to adopt a new approach after the Facebook/WhatsApp debacle. Google is acquiring Fitbit for its data and therefore the competitive assessment should reflect that. Moreover, the Commission should use this case as an opportunity to consult with consumer and data protection authorities.

Read more:

Google wants to acquire Fitbit, and we shouldn’t let it! (13.11.19)

https://privacyinternational.org/news-analysis/3276/google-wants-acquire-fitbit-and-we-shouldnt-let-it

GOOGLE-FITBIT MERGER: Competition concerns and harms to consumers (07.07.20)

http://www.beuc.eu/publications/beuc-x-2020-035_google-fitbit_merger_competition_concerns_and_harms_to_consumers.pd

Considering Data Protection in Merger Control Proceedings (06.06.18)

https://one.oecd.org/document/DAF/COMP/WD(2018)70/en/pdf

Competition law: what to do against Big Tech’s abuse? (01.04.2020)

https://edri.org/competition-law-what-to-do-against-big-tech-abuse/

The impact of competition law on your digital rights (19.02.2020)

https://edri.org/the-impact-of-competition-law-on-your-digital-rights/

(Contribution by Laureline Lemoine, EDRi senior policy advisor)