#PrivacyCamp21: Event Summary

The theme of the 9th edition of Privacy Camp was "Digital rights for change: Reclaiming infrastructures, repairing the future" and included thirteen sessions on a variety of topics. The event was attended by 250 people. If you missed the event or want a reminder of what happened in the session, find the session summaries below.

With a legacy of almost a decade, this year Privacy Camp zoomed in on the relations between digitalisation, digital rights and infrastructures. Sessions formats ranged from panels (speakers addressing the audience) to more interactive workshops (speakers address + audience engagement experiences). What were these about? Read below a summary of each discussion.

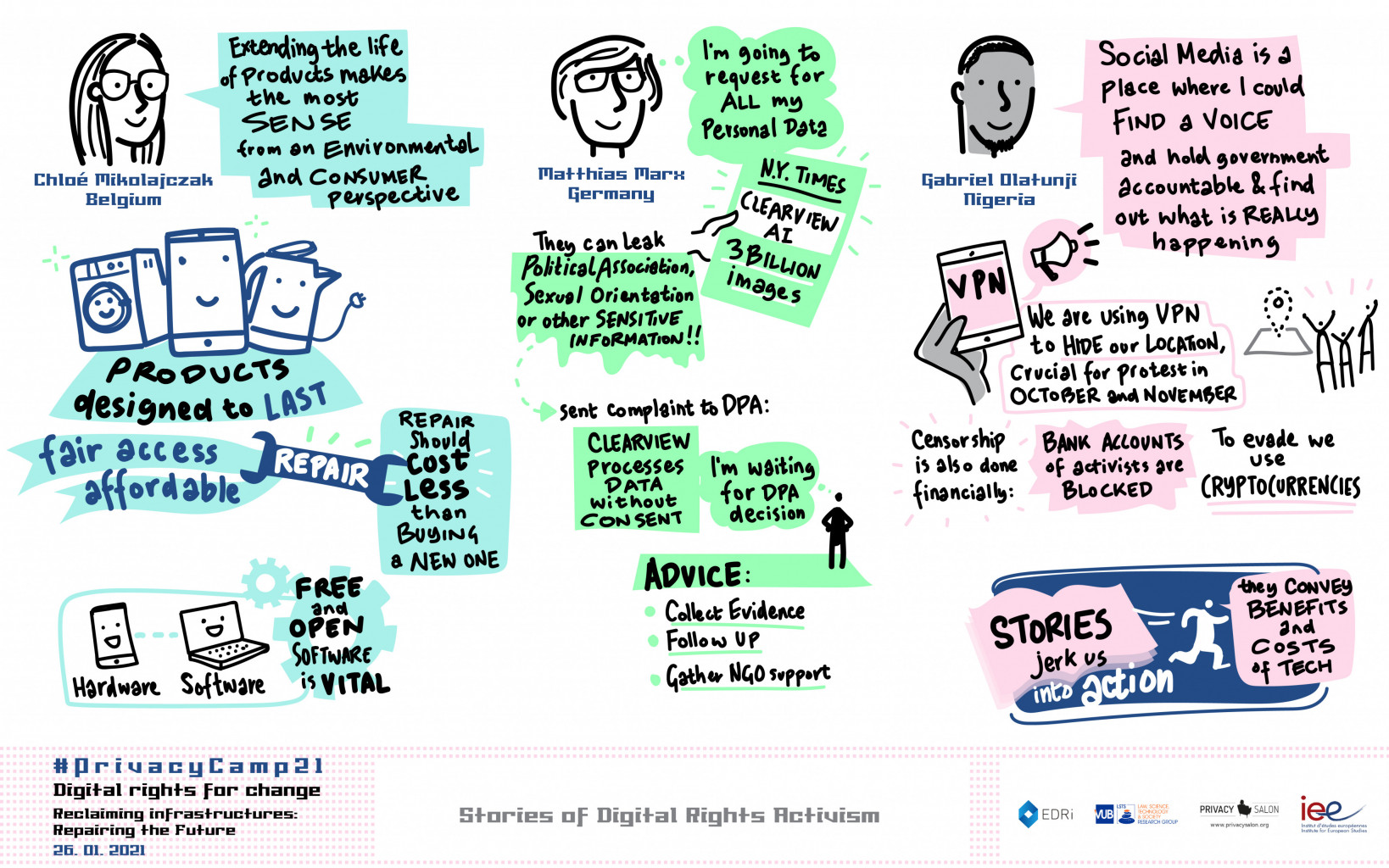

Storytelling session: Stories of digital rights activism

Stories are important because they jerk us into action. They are critical to convey our message about the benefit and costs of technology. This session invited 3 digital rights activists to share their stories. Chloé Mikolajczak from Belgium talked about the Right to Repair campaign that hopes to extend the life of products benefiting the environment and consumers alike. The campaign asks Policy makers to ensure that products are designed to last, that everyone has fair access to repair, and access to affordable repair. Repairing a product should not cost more than buying a new one. This should apply to hardware but also software – which is why free and open software is vital.

Next, Matthias Marx from Germany told us about how a New York Times article on Clearview AI, a company controlling a database which includes 3 billion images, inspired him to send an access request for all his personal data. He also took us through the process of sending a complaint to the Hamburg DPA saying that Clearview processed data of European residents without consent. As a result, the Hamburg DPA has now deemed Clearview AI’s biometric photo database illegal in the EU.. His advice to us was to collect evidence, follow up and gather support from NGOs if we want to send similar data access requests.

Last but not least, Gabriel Olatunji from Nigerian talked about how he used social media to find a voice, hold the government accountable and find out what is really happening. He shared how activists were arrested and intimidated constantly by the government, including kidnapping of activists who are tracked using technology. He uses tools like VPNs, cryptocurrencies and encrypted communication technologies to safety organise and resist government interference and shutdown.

A new model for consent? Rethinking consent among complex infrastructures and complex explanations

The panel discussed a more organic approach to consent within the data protection sphere. The black-letter law states that consent is only valid if it is “free, specific, informed, and unambiguous”. Yet these terms cannot be taken as a simple recipe, with clearly defined ingredients and steps. The reality of consent is more fluid: it does not automatically follow from an aseptic and formal exercise of information-provision or box-ticking. The panel first provided a list of real-life cases where the consent was inconsistently used, even by public bodies. The moderator then focused on two of the main requirements of consent: information and free will. In terms of information, one of the panellists suggested a more substantive approach which included an added element of effective “comprehension” and control over the processing.

The second panellist focused on the notion of “free consent”, considering the conditioning of services and power imbalances, especially with regards to vulnerable data subjects. The final panellist shed light on how users intend consent in their daily interaction with apps and new technologies. Picking up on the recent update by Whatsapp to their terms, which required users to consent to data being shared with Facebook, the speaker also pointed out that if users understand the processing, then they are not passive and instead can proactively take action. For example, many users in Europe changed their messaging app after the consent request from Facebook-Whatsapp.

Finally, the moderator launched the Q&A session. Among other comments, the panel briefly discussed the so-called ‘common European data altruism consent’. Building upon these elements, the panel concluded that most of the consent given online could be invalid, especially in situations of extremely complex processing operations.

Local perspectives: E-life and e-services during the pandemic

The panel explored the key trends linked to the digitalisation of our lives and the external factors that have influenced the level of respect of our basic digital rights in Southeast and Central Europe. Under the excuse of “flattening the curve” governments in the region have undertaken extreme measures that have severely affected the media freedom and the privacy of people including the most vulnerable groups. While states are implementing different tech solutions to overcome the existing challenges without any strategy, the citizens are left without any protection in the digital arena.

Jelena Hrnjak (Programme Manager, ATINA NGO) highlighted the challenges that vulnerable groups in Serbia experience as a result of the digital gap. ATINA’s report on human trafficking victims’ abuse in digital surroundings shows that girls and women in Serbia have been exposed to a high prevalence of abuse in digital surroundings prior, during and after the trafficking situation. Nevena Martinovic (Share Foundation) underlined the rising digital issues during the pandemic, in particular media freedom, the spread of misinformation and the numerous data breaches. Thus, transparency is the crucial point in the e-life to overcome all the obstacles of e-governance, especially for state actions. Elena Stojanovska (Metamorphosis) brought the case of the newly adopted law in Serbia in February 2020 which introduced several problematic ideas. It envisioned a publicly available list of COVID-19 positive people’s details which could have led to victimisation and discrimination of these people. Additionally, it approved the launch of a Corona tracing app without clear information about who was responsible for the collected data and whether the application was useful or efficient. Thanks to Metamorphosis these issues were addressed and the negative consequences mitigated. On a more positive note, Dr Katrin Nyman-Metcalf (e-Governance Academy) provided some examples of the state of the digitalisation in Estonia during the pandemic. Considering that Estonia has been one of the leading Member States in the development of the digitalisation sector, the country did not face significant problems during the pandemic. The e-services proved to be efficient, technologies effectively protected people’s data and the established transparency and privacy mechanisms ensured human rights are not violated.

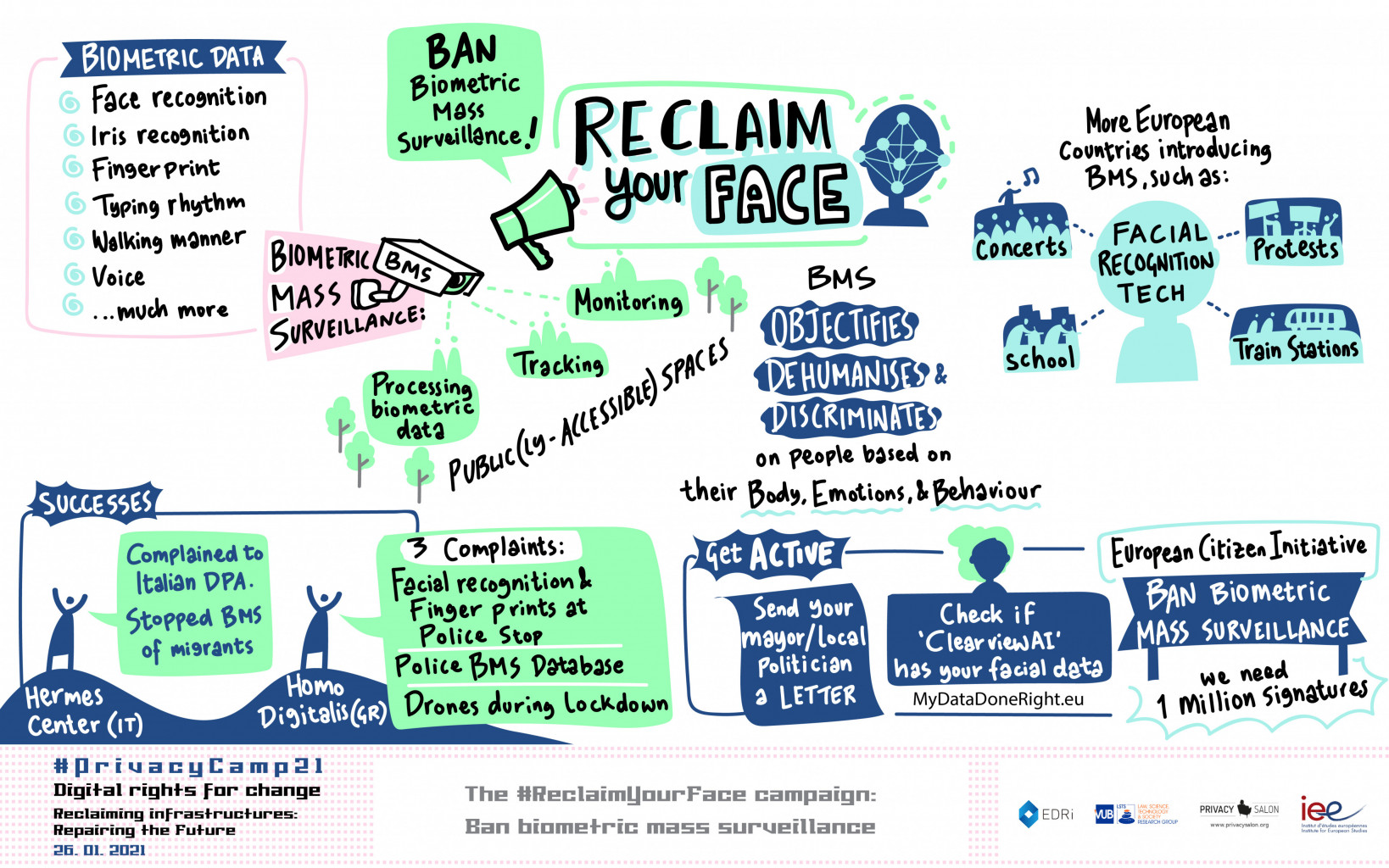

The #ReclaimYourFace campaign: Ban biometric mass surveillance

This interactive workshop was split in 3 parts. The first part had EDRi’s Andreea Belu give an overview of the ReclaimYourFace campaign coalition and actions challenging biometric mass surveillance, the EU law-making in regards to the next AI legal framework and the reasoning why over 30 organisations are calling for a ban on biometric mass surveillance.

Secondly, Riccardo Collucini (Hermes Center – Italy ) and Eleftherios Chelioudakis (Homo Digitalis – Greece) provided details on national contexts. Riccardo detailed the legal challenge against Italian City of Como’s authorities deploying biometric surveillance against migrants and the fight against the national SARI system. Eleftherios (Homo Digitalis) mentioned the legal complaints against the Hellenic Police’s plans to use of biometrics during stop & searches, the resulting investigation by the Hellenic Data Protection Authority, as well as the use of drones cameras for surveiling the Greek population.

In the third part, participants learnt how to best address their local politicians using a letter asking for commitment against biometric mass surveillance. Finally, participants learnt how to use the mydatadoneright.eu data subject access requests tool to understand what the notorious face-scraping ClearviewAI company knows about them.

Wiring digital justice: Embedding rights in Internet governance ‘by infrastructure’

The panel discussed how the language of rights/freedoms can be translated in infrastructures, and the complexities arising from this process. The panel covered different types of configurations in which the ’embedding’ of freedoms into infrastructure takes shape, from more ‘traditional’ Internet governance arenas to grassroots initiatives.

Amelia Andersdotter (CENTR) pointed out how technical standards bodies produce voluntary standards and their outputs are always subsidiary to actual law; she shared the example of 5G development, where end-to-end security is a priority for private networks in industrial applications, but seen as a threat when it comes to public networks that people use. Mehwish Ansari (ARTICLE19) focused on the International Telecommunications Union (ITU) and noted that it has become a space where ‘usual suspect’ actors can consolidate their claim to power in a world that is increasingly moving toward “global governance”, where non-state actors have some transnational decision-making power (albeit still in a state-centric system). Ksenia Ermoshina (CNRS) adopted a grassroots and tech activism perspective as she described her observations of a growing demand for alternative communication protocols that can help respect our right to communicate in critical times. She provided examples of P2P secure messaging applications and mesh networking. Niels ten Oever (University of Amsterdam/Texas A&M University) pointed out two concurrent scenarios in the field: either internet governance options incorporate structural considerations for societal impact in their policy, standardisation and development issues, or states will take up an even greater role in rule setting for information networks. Finally, Bianca Wylie (CIGI) noted that a site of considerable opportunity for intervention in infrastructures is through procurement, as a place to write requirements for protocols and other methods of reclaiming private infrastructure for public purpose.

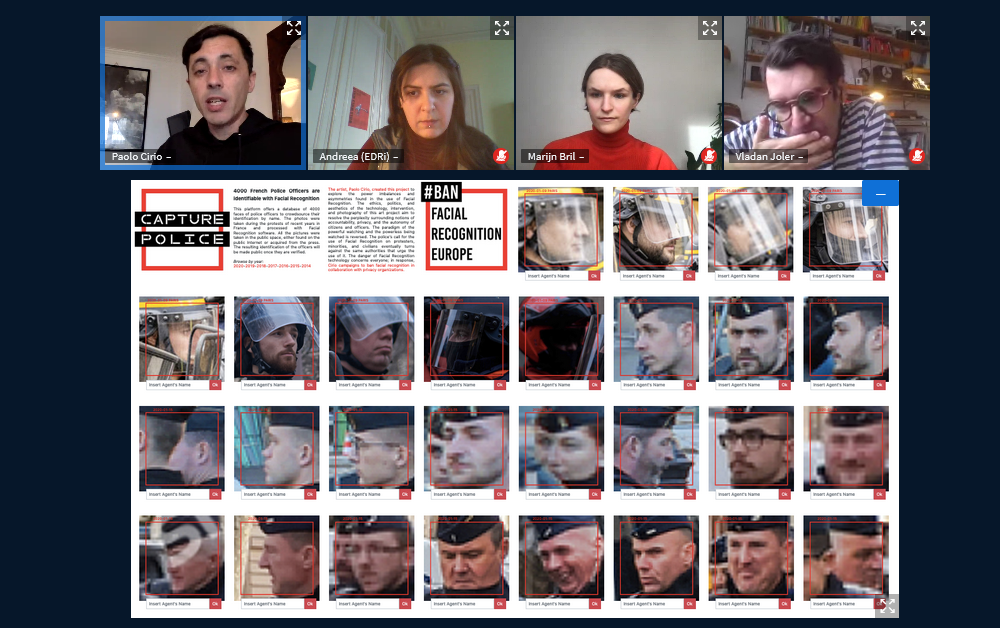

On Art and Digital Rights Activism

The session began with an introduction into the work of the 3 artists on the panel. Vladan Joler spoke about his focus on critical cartography visualising on huge surfaces the extent to which algorithms exploit natural and human resources. Marin Bril explained her focus on employee surveillance and the investigations into the effects of quantification on the way we ascribe value to work, while Paolo Cirio described his latest project focused on collecting pictures of police officers during protests in France over the past years from Google and journalists.

The discussion continued around the notion of quantification, to which Vladan pointed that much of that to which attention should be paid to is invisible and cannot be quantified (invisible and immaterial labour, emotion economy). Marijn added that, while facial expressions & heart beats can be quantified, real feelings cannot. When the moderator Andreea Belu (EDRi) questioned art’s value to understand digital rights issues, Paolo emphasised the need to visualise dangers in order to raise awareness, as shown by the reactions he received to his work. Vladan pointed that visualisation must be understood from the perspective of the visualiser (added note: situated knowledge). Marijn concluded that art can help organise dissent during the pandemic due to its value of being circulated on social media, create narrative and break audience bubbles.

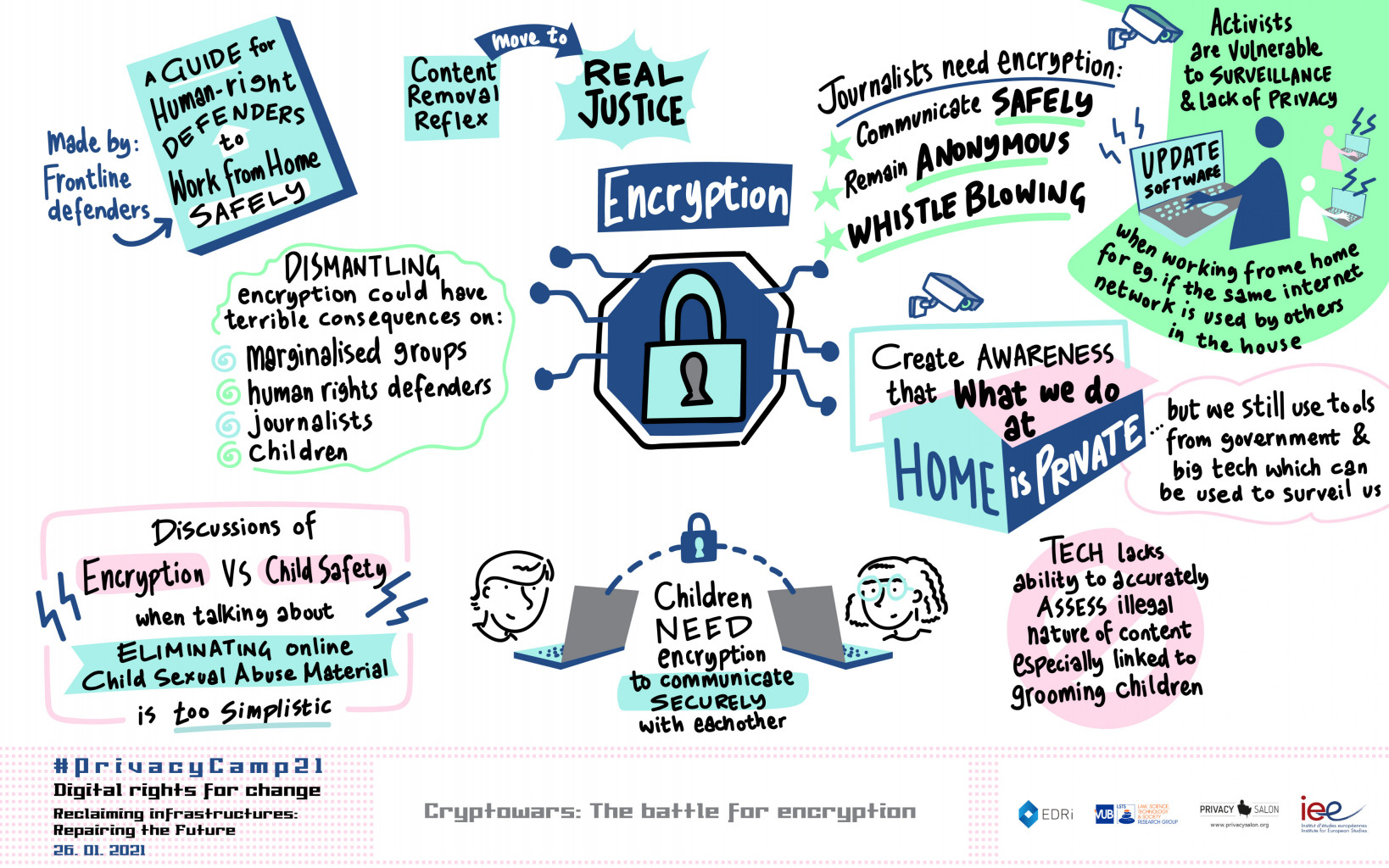

Cryptowars: The battle for encryption

During this panel we discussed the growing trends and legislative initiatives to scan private communications to prevent the dissemination of illegal material. In order to discuss the need to strengthen encryption and confidentiality of communications we invited representatives of children rights’ groups, human rights defenders and journalists.

Jen Persson, DefendDigitalMe kicked off the discussions of encryption versus children safety saying that eliminating child sexual abuse material online is too simplistic and that we must move from a content removal reflex to real justice. Furthermore, there was agreement among panelists that dismantling encryption could have terrible consequences on many marginalised groups including human rights defenders, journalists, children and adults alike. Tom Gibson, EU Representative and Advocacy Manager at the Committee to Protect Journalists reminded us that journalists need encryption to: communicate safely with sources, remain anonymous and for whistleblowing like in the case of the Panama papers. Leo Ratledge from Child Rights International (CRIN) highlighted that children need encryption to communicate securely with each other. Regarding the use of scanning technologies on private conversation to detect child abuse, Persson said that technology does not have the ability to accurately assess the illegal nature of content especially linked to grooming children, distinguish between parody etc. Wojtek Bogusz, Head of the Digital Protection team at Front Line Defenders told us that activists are especially vulnerable to surveillance and lack of privacy when working from home if they do not have up-to-date software, the internet network is used by other people in the house or they access websites without protection. They have however created a guide for human-right defenders to work from home safely and securely.

Finally, when working from home, he said that we need to create awareness that what you do at home is private but tools from the government and big tech are still used by children and adults (including human rights defenders) at home which can be used for more data collection and surveillance purposes.

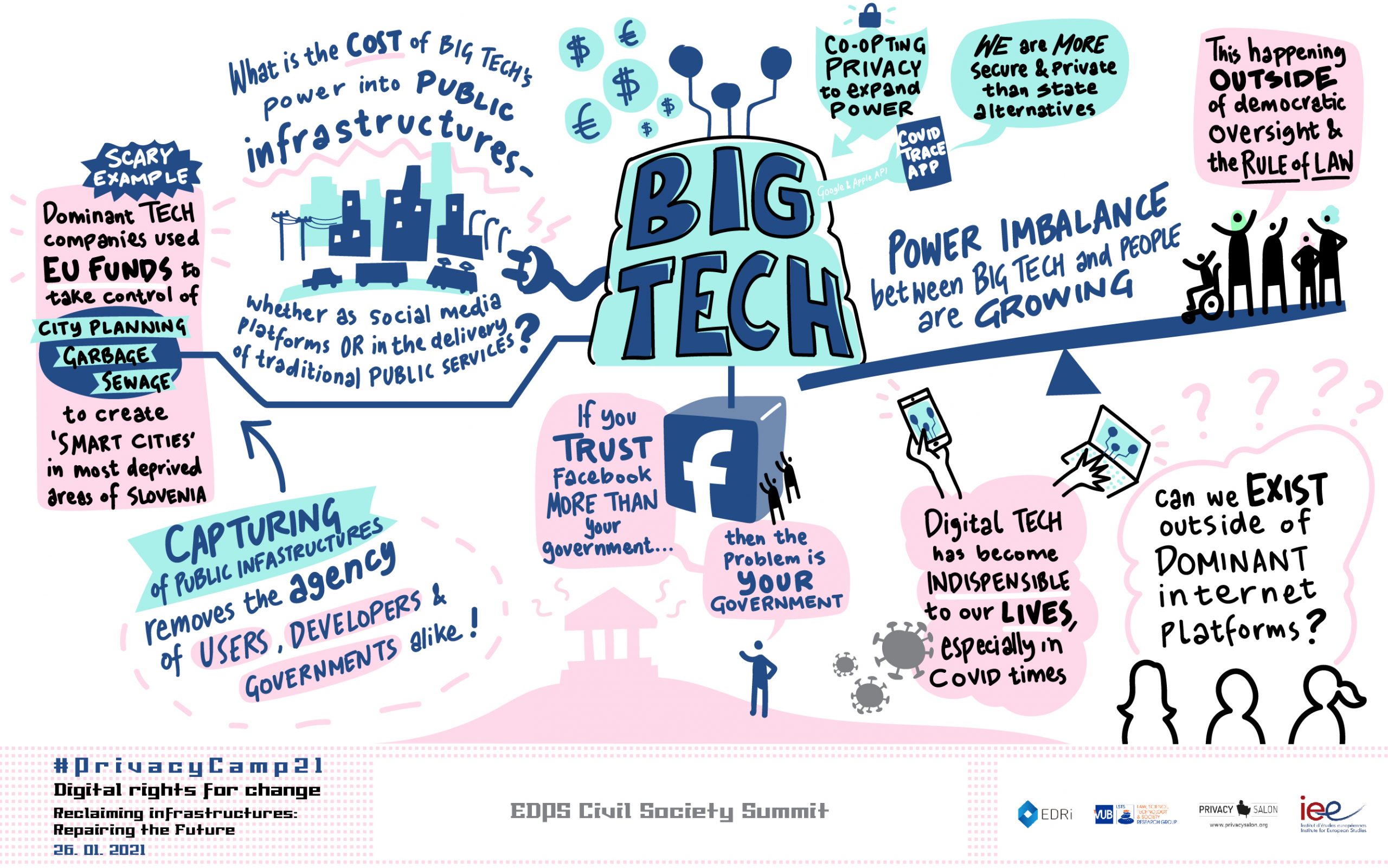

The EDPS Civil Society Summit “Big tech: from private platforms to public infrastructures”

Big Tech’s “power-grabs” in public domains such as healthcare, education, and public administration have huge implications on our individual rights – but will also fundamentally alter what is “public” in our societies. This dominance once maintained through data extraction from its user base on large platforms has now shifted, before and during the Covid-19 pandemic, expanding the reach of technology companies deeper into “public domains”. Every year at its annual event Privacy Camp, EDRi discusses a major issue of digital rights with the European Data Protection Supervisor at the Civil Society Summit. Big Tech’s growing dominance in the public sphere was the focus of the 2021 session. Our panellists came to the issue from different angles; concerning freedom of expression on social media platforms (Gabrielle Guillemin, Article 19) the involvement of technology companies in “Smart Cities” (Domen Savič, Državljan D) and the mechanics of how technology companies have secured their power through computational infrastructures (Dr Seda Gürses, TU Delft.

The European Data Protection Supervisor, Wojciech Wiewiórowski, responded with the implications for the European data protection framework. Twitter’s permanent suspension of then President Donald Trump on 8th January was a power move unlike any other. It showed that, despite the “public”, global and widespread user-base of the platform, the corporation decides the rules of the game, including free speech. However, the domination doesn’t stop at our speech and data. The technology industry, estimated at a value of over $6 trillion – and is now more valuable than the entire European stock market, according to a Bank of America Global research – has expanded its reach far beyond social media. This expansion comes in several forms. One, as uncovered by the Tracking Smart Cities project in Slovenia, involves the provision of infrastructure to public institutions. Often offered at little or no-cost, or funded by research and innovation projects like the EU’s Horizon 2020, companies are able to capture the market by providing technical ‘solutions’ to social problems. In small, often poor, cities in Slovenia, small-scale issues like rat infestations and rubbish disposal has been offered up for private involvement via “Smart Tech”. Whilst these may seem like small-scale interventions, we see the same trends replicated elsewhere in areas such as security, policing and migration, with a vast potential for human rights breaches and discrimination. The full potential extent and impact of private sector involvement in these fields was exposed this week in the Frontex Files.

We need to demand more than legal frameworks that place the burden for contesting harms on the shoulders of individuals. We cannot simply hope that dominant corporations will benevolently opt to uphold individual rights even if this threatens their market power and profits. Even with regulation, this has been tricky, to say the least.

The Privatised Panopticon: Workers’ surveillance in the digital age

![]()

The global pandemic crisis has increased some trends related to work and surveillance that were already happening. First, with the rise of working from home, in some cases employers have tried to keep tight control of the workforce via the use of different types of software (Zoom, Microsoft Office). Second, the increase of eCommerce and the huge growth of Amazon has also raised concerns about the impact of surveillance on workers. Increasingly, the link between labour and digital rights is more obvious, and the need to bring coalitions together against specific threats are of utmost importance.

During this panel Alba Molina-Serrano, Pre-doctoral researcher at Eurofound Correspondent told us how worker technology is being used in 3 human resources processes: recruitment; assessment and monitoring and firing. She added that research published by Data Science Lab found a multitude of control techniques, such as wearable devices monitoring, workforce scheduling, turnover, profiling and optimisation. Aída Ponce, from the European Trade Union Institute told us that because of the imbalance between employees and employers, the use of technologies always tips this power imbalance to the advantage of the employers. This imbalance is even bigger when it comes to workers from the gig economy (deliveroo, uber etc) because of the lack of protection. We learned from Nick Rudikoff from UNI Global Union how Amazon is a perfect example of powerful companies operating a surveillance system to control its own workforce to drive a new standard of taylorism and modern exploitation and that these same technologies help employers more effectively push back against worker’s coming together to protest. Renata Ávila from Progressives International is a representative of the #MakeAmazonPay campaign. She reminded us that privacy is a collective issue and not an individual one and that we need to know how technologies are made, deployed and what their impact is on workers’ life, outside of criminal procedures. We need to expose companies whose goals run against our societies’ welfare.

During this panel we learned how technologies risk deepening discrimination against women since the design of the metrics and performance standards in terms of high productivity are led by men and that digitalisation is spreading rapidly in every sector, including logistics, transportation and healthcare. Finally, we discussed workers surveillance specifically: Before, cameras might have been used to ensure safety regulations are complied with for the benefit of employees. Now, these can be used to surveil workers. So, this “excuse” of safety needs to be clarified too. A specific threat is the emotional monitoring of workers, a technology that is now possible and used. Ponce called for a ban on emotional surveillance such as monitoring attention and facial features to determine productivity.

Reclaim Your Face, Reclaim Your Space: resisting the criminalisation of public spaces under biometric mass surveillance

In the panel “Reclaim Your Face, Reclaim Your Space”, EDRi’s Ella Jakubowska was joined by Vidushi Marda of NGO ARTICLE 19, MEP Karen Melchior and Dr Stefania Milan from the University of Amsterdam. They used the panel to explore how blanket biometric surveillance can transform the sanctuaries of our public spaces into loci of suspicion and unfair, undignified judgment. In particular, Karen emphasised the problem of shrinking public spaces due to privatisation, which are changing the rules for how we are supposed to act in public. Stefania added that the public space is so vital because it acts as a front page for social change, where demands are articulated and brought to the public. Vidushi agreed that public spaces are epicenters of our political rights and therefore rely on privacy – but that biometric mass surveillance can intimidate people, and flips the burden of protection by denying our fundamental rights until these pseudo-scientific systems grant them.

The panelists continued by dissecting the issue of how technologies criminalise people in public: Karen explained how the fact of being mistrusted by authorities can make us mistrust them in return, which undermines the good functioning of democracy. She emphasised the problem that we are outsourcing to algorithms judgements that humans have been making for thousands of years but still find difficult. Vidushi added how safety has been a Trojan horse for the expansion of surveillance, and legal safeguards for exceptional circumstances have been abused. Stefania concluded that whilst our agency can be harmed by these tools, there are lots of creative modes of resistance; and that we can have not only alternative futures, but also an alternative present. Throughout the panel, Ella emphasised the Reclaim Your Face campaign which launched in November 2020 and will be taking pan-European action from February 2021 in order to ban biometric mass surveillance in the EU.

Teach me how to hurdle: Empowering data subjects beyond the template

Data subjects wishing to exercise their data access rights face a variety of obstacles. Some derive from their limited knowledge of applicable rules. Many, however, are due to data controllers’ problematic responses – or lack of response – to requests, which can leave even the most advanced and confident data subject in a state of perplexity, helplessness, or despair. This workshop looked at ways in which individuals can self-organise and help each other, or help others in their community, for the exercise of data protection rights.

In addressing law in practice, René Mahieu (Researcher LSTS/VUB) shared his experience through his PhD of the work he is doing on empowering data subjects beyond the template. After having his research participants submit access requests, they expressed a complete understanding of the importance of digital rights but felt disempowered because of the complicated process of obtaining access to their data. Thus, providing guidance in a more simple and accessible manner for people to understand data subjects right is essential. While Data Protection Authorities and digital rights NGOs provide templates for exercising data subject rights in a legally compliant way, more easily accessible information is needed.

Ana Pop Stefanija (Researcher at SMIT, VUB) emphasised the usefulness of templates in the process as they provide data subjects with learning material. It is often the case that companies just provide a link to the data protection notice, and avoid giving a proper response. While individuals must be empowered to know and seek their rights, it is companies that should take the burden to provide clear, understandable information. The project that Safa Ghnaim (Project Lead, Data Detox Kit at Tactical Tech) is working on called the Data Detox kit offers such information on what people can do to protect their digital rights. The kit translates the technical terminology into more easily understandable information which can help data subjects understand what data belongs to them, and how to protect it by making an informed choice about the trade-off of using certain platforms, and services. In relation to that, Olivier Matter (European Data Protection Supervisor Office) raised the question of the need to be concise but yet provide exhaustive information which is a contradiction that affects the effectiveness of the provided guidance. Also, he announced that the EDPS will be releasing its guidelines on the right of access before the summer.

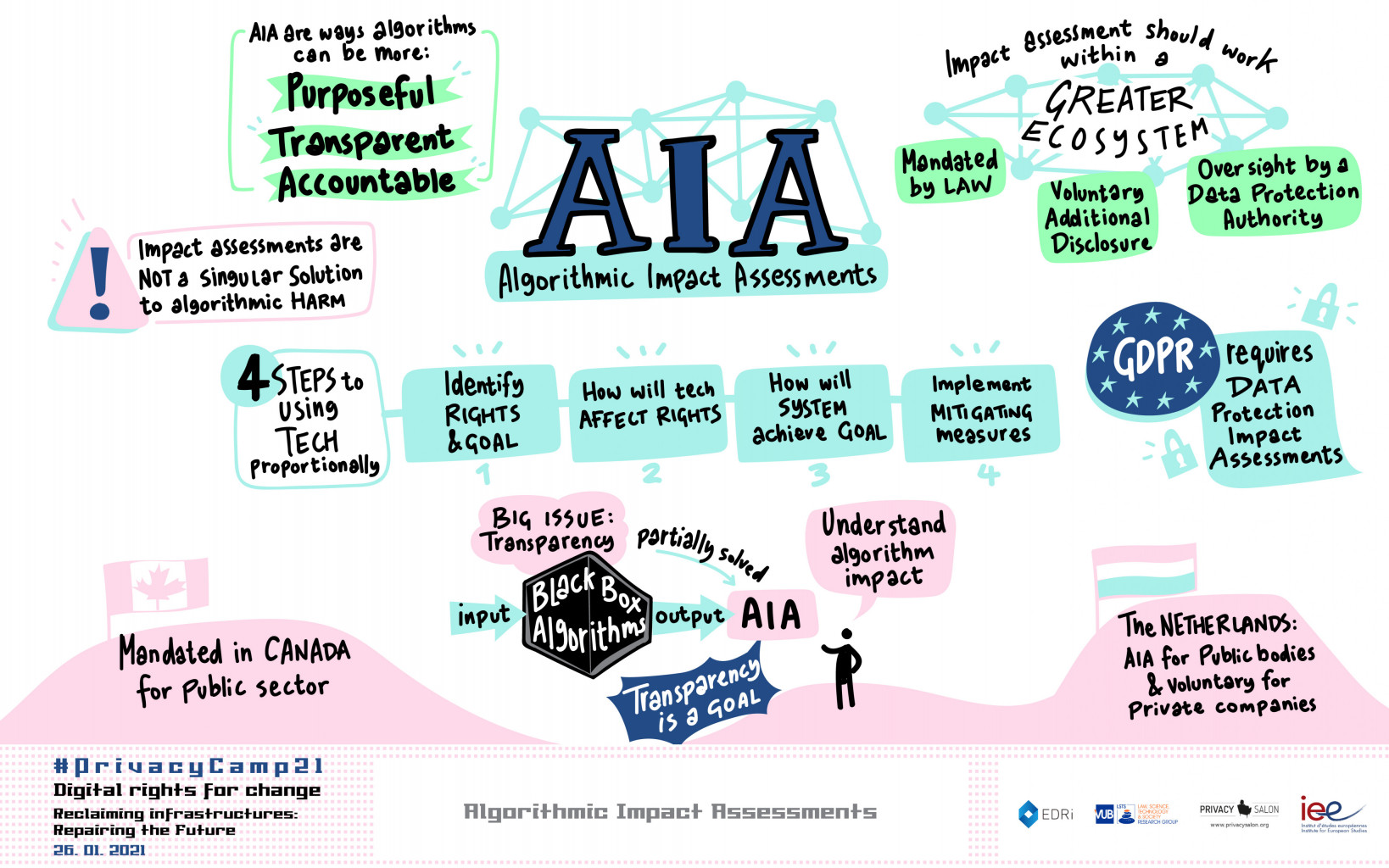

Algorithmic Impact Assessments

The EPIC panel introduced what algorithmic impact assessments are, how these assessments can be made effective, and what the implications are of requiring assessments for public and private use. A Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA) is a process to help you identify and minimise the data protection risks of a project. Under the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) DPIA also refers to processing that might result in a high risk to the rights and freedoms of individuals. Dr Gabriela Zanfir-Fortuna (Senior Counsel of Global Privacy at Future of Privacy Forum) underlined that the DPIA must take into account all the rights and comply with all conditions listed under Article 35 (GDPR). The GDPR requires four types of analysis: (i) systematic assessment; (ii) assessment of necessity and proportionality; (iii) assessing rights to freedom; and (iv) assessment of the measures to address the identified risks.

European data protection authorities (DPA) have been doing a lot of work on algorithmic impact assessments. For example, the Spanish DPA has published an audit framework for algorithmic systems, which has to be used for algorithms that already exist. Furthermore, in the next years, the European Data Protection Board (EDPB) plans to focus on fundamental rights and technology, with a focus on AI and biometric technologies. The Council of Europe is also developing a framework on democracy and the rule of law, and AI.

In her work, Heleen Louise Janssen (Researcher at IVIR Institute for Information Law at the University of Amsterdam) focused on operationalising the impact assessment on fundamental rights using the GDPR as a benchmark. The reason for developing a system was that in discussing impact assessments, the Dutch government concentrated solely on technology rather than also incorporating concepts like ‘rule of law’ or ‘democracy’. Heleen’s system includes four stages:

- Identify the rights at stake

- How will technology (AI/ automated decision making/ mix) affect these rights?

- Is the system necessary to achieve the goal and is it proportionate?

- What are organisational or technical mitigating measures? Once implemented, go back to 2 until you decide you have a safe AI system.

The panel discussion concluded that impact assessments should be mandatory, and law prescribed. However, these should be complemented by voluntary schemes. What is essential is to provide guidance to companies that do not understand fundamental rights and the differences between core and peripheral rights, etc.

Platform resistance and data rights

This session drew an engaging discussion on how data rights can, and should, empower individuals and communities to resist private platform power. Moderator, Jill Toh (University of Amsterdam) introduced a multi-disciplinary panel which included Bama Athreya (Open Society Foundation), Gloria Gonzalez Fuster (Research Professor, Vrije Universiteit Brussel), and Rebekah Overdorf (École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne). The first question, on the tensions between the individual and collective dimension of data rights, provoked a lively debate. Bama pointed out that we still lack the capacity to collectively decide how to govern data, as the libertarian capitalist world view of data dominates debates. She suggested looking to Global South activists on collective data rights can be productive. Rebekah added that as technologies are increasingly based on groups, this individual vs collective dimension needs to be rethought. Gloria took the view that the GDPR are individual rights that offer collective value, and often, the issue lies in a matter of framing and perception.

The next question zoomed in on the role of civil society in organising data rights as tools for platform resistance. The panelists stressed the importance of bridging digital rights work with the practical reality of communities on the ground, including legal expertise and strategies on organising. The example of the Deliveroo Italian court case on algorithmic management was discussed, with Gloria reiterating the need to ensure strong GDPR enforcement and Bama highlighting the importance of unions and legal tools. Rebekah noted the dual-use nature of data rights and called for technical means to ensure that privacy can be maintained. She cautioned that we need to remember that our problems do not come from where we are but how we got here.

In conclusion, the panelists agreed that the current set up and close relationships between private tech companies and governments are problematic as citizens are often left out of the process. Asymmetry to resources is a factor, and civil society has to leverage their ability to organise collective action, not only against private companies, but to hold governments to account too.

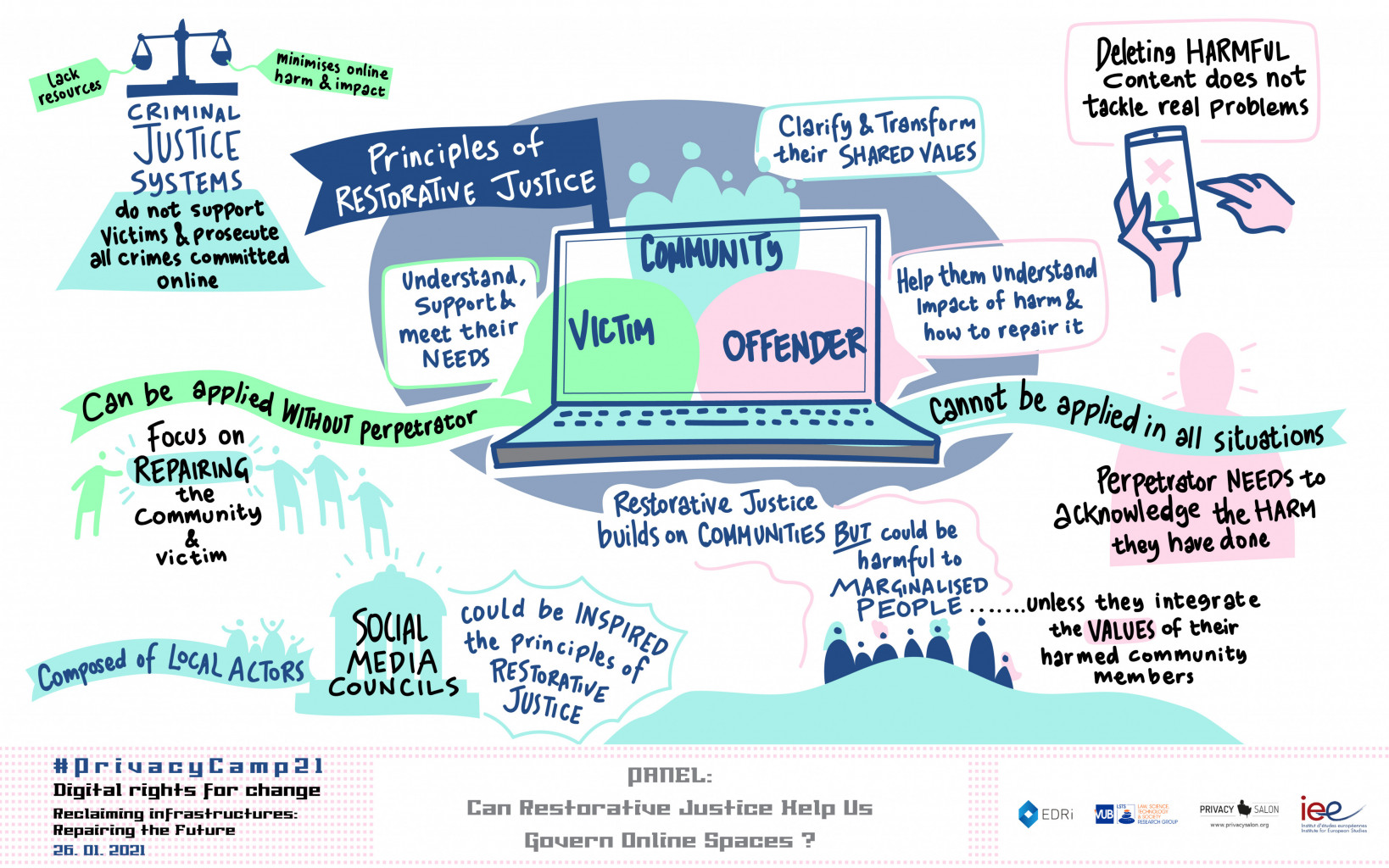

Can Restorative Justice Help Us Govern Online Spaces?

With a background in media and cultural studies focusing on gender and sexuality in the context of new media, Dr. Amy Hasinoff kicked off the session highlighting the shortcomings of a traditional content moderation approach, which offers some relief to victims but does not tackle the real underlying problems. Just like prison in the current criminal justice system removes the person who has done the harm from society, commercial content moderation performed by platforms is a punitive model where harmful content is simply removed. This process deprives people from understanding the conflicts. She then introduced the principles of restorative justice which take into account the needs of the person who did harm, the person who was harmed and the community. Finally she listed the conditions to apply restorative justice online: one must devote resources, support facilitators, allow openness and foster community transformation when the community has not yet integrated important values (such as gender equality).

Josephine Ballon followed by explaining the work of her orgnaisaiton, HateAid, which is a counseling center for affected people in Germany, offering cybersecurity advice, emotional and financial support. Joesphine shared the frustration of working with law enforcement authorities to enforce the law on the internet, as it is complex and time-consuming to identify perpetrators and there is minimisation from society of the harm experienced by online harassment victims. Pierre-François Docquir from ARTICLE 19 reported on the idea of Social Media Councils and how it developed. Social Media Councils would be composed by local actors, emphasising the community dimension as they would bring all interested parties together for a solution and mutual understanding. Therefore, their functioning can be inspired by the principles of restorative justice. Lastly, Alexandra Geese MEP reminded the audience that currently harmful content and not only illegal content can be the source of self-censorship for marginalised users such as women, who are still afraid of speaking online, thus affecting their freedom of expression. She supports the creation of Social Media Councils that should have the task to recreate debate with the public over what it is acceptable online or not. For her, the EU legislation needs to combat the commercial surveillance model of existing internet companies that are also at the source of the spread of harmful and illegal content.

What was your favourite session this year? Let us know by tweeting your thoughts with the hashtag #PrivacyCamp21.

- #PrivacyCamp2021 – Programme