The many faces of facial recognition in the EU

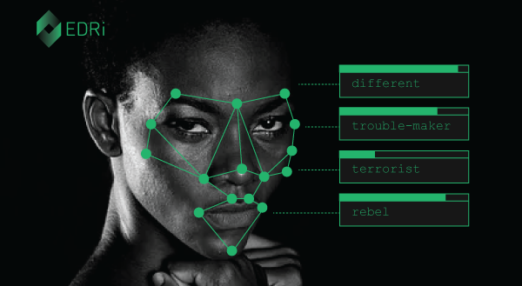

In this second installment of EDRi's facial recognition and fundamental rights series, we look at how different EU Member States, institutions and other countries worldwide are responding to the use of this tech in public spaces.

We previously launched the first article and case study in a series exploring the human rights implications of facial recognition technology. In this post, we look at how different EU Member States, institutions and other countries worldwide are responding to the use of this tech in public spaces.

Live facial recognition technology is increasingly used to identify people in public, often without their knowledge or properly-informed consent. Sometimes referred to as face surveillance, concerns about the use of these technologies in public places is gaining attention across Europe. Public places are not well-defined in law, but can include open spaces like parks or streets, publicly-administered institutions like hospitals, spaces controlled by law enforcement such as borders, and – arguably – any other places where people wanting to take part in society have no ability to opt out from entering. As it stands, there is no EU consensus on the legitimacy nor the desirability of using facial recognition in such spaces.

Support our work

Donate now

Public face surveillance is being used by many police forces across Europe to look out for people on their watch-lists; for crowd control at football matches in the UK; and in tracking systems in schools (although so far, attempts to do this in the EU have been stopped). So-called “smart cities” – where technologies that involve identifying people are used to monitor environments with the outward aim of making cities more sustainable – have been implemented to some degree in at least eight EU Member States. Outside the EU, China is reportedly using face surveillance to crack down on the civil liberties of pro-democracy activists in Hong Kong, and there are mounting fears that Chinese surveillance tech is being exported to the EU and even used to influence UN facial recognition standards. Such issues have brought facial recognition firmly onto the human rights agenda, raising awareness of its (mis)use by both democratic and authoritarian governments.

How is the EU grappling with the facial recognition challenge?

Throughout 2019, a number of EU Member States responded to the threat of facial recognition, although their approaches reveal many inconsistencies. In October 2019, the Swedish Data Protection Authority (DPA) – the national body responsible for personal data under the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) – approved the use of facial recognition technology for criminal surveillance, finding it legal and legitimate (subject to clarification of how long the biometric data will be kept). Two months earlier, they levied a fine of 20 000 euro for an attempt to use facial recognition in a school. Similarly, the UK DPA has advised police forces to “slow down” due to the volume of unknowns – but have stopped short of calling for a moratorium. UK courts have failed to see their DPA’s problem with facial recognition, despite citizens’ fears that it is highly invasive. In the only European ruling so far, Cardiff’s high court found police use of public face surveillance cameras to be proportionate and lawful, despite accepting that this technology infringes on the right to privacy.

The French DPA took a stronger stance than the UK’s DPA, advising a school in the city of Nice that the intrusiveness of facial recognition means that their planned face recognition project cannot be implemented legally. They emphasised the “particular sensitivity” of facial recognition due to its association with surveillance and its potential to violate rights to freedom and privacy, and highlighting the enhanced protections required for minors. Importantly, France’s DPA concluded that legally-compliant and equally effective alternatives to face recognition, such as using ID badges to manage student access, can and should be used instead. Echoing this stance, the European Data Protection Supervisor, Wojciech Wiewiórowski, issued a scathing condemnation of facial recognition, calling it a symptom of rising populist intolerance and “a solution in search of a problem.”

A lack of justification for the violation of fundamental rights

However, as in the UK, the French DPA’s views have frequently clashed with other public bodies. For example, the French government is pursuing the controversial Alicem digital identification system despite warnings that it does not comply with fundamental rights. There is also an inconsistency in the differentiation made between the surveillance of children and adults. The reason given by both France and Sweden for rejecting child facial recognition is that it will create problems for them in adulthood. Using this same logic, it is hard to see how the justification for any form of public face surveillance – especially when it is unavoidable, as in public spaces – would meet legal requirements of legitimacy or necessity, or be compliant with the GDPR’s necessarily strict rules for biometric data.

The risks and uncertainties outlined thus far have not stopped Member States accelerating their uptake of facial recognition technology. According to the EU’s Fundamental Rights Agency (FRA), Hungary is poised to deploy an enormous facial recognition system for multiple reasons including road safety and the Orwellian-sounding “public order” purposes; the Czech Republic is increasing its facial recognition capacity in Prague airport; “extensive” testing has been carried out by Germany and France; and EU-wide migration facial recognition is in the works. EDRi member SHARE Foundation have also reported on its illegal use in Serbia, where the interior ministry’s new system has failed to meet the most basic requirements under law. And of course, private actors also have a vested interest in influencing and orchestrating European face recognition use and policy: lobbying the EU, tech giant IBM has promoted its facial recognition technology to governments as “potentially life-saving” and even funded research that dismisses concerns about the ethical and human impacts of AI as “exaggerated fears.”

As Interpol admits, “standards and best practices [for facial recognition] are still in the process of being created.” Despite this, facial recognition continues to be used in both public and commercial spaces across the EU – unlike in the US, where four cities including San Francisco have proactively banned facial recognition for policing and other state uses, and a fifth, Portland, has started legislative proceedings to ban facial recognition for both public and private purposes – the widest ban so far.

The need to ask the big societal questions

Once again, these examples return to the idea that the problem is not technological, but societal: do we want the mass surveillance of our public spaces? Do we support methods that will automate existing policing and surveillance practices – along with the biases and discrimination that inevitably come with them? When is the use of technology genuinely necessary, legitimate and consensual, rather than just sexy and exciting? Many studies have shown that – despite claims by law enforcement and private companies – there is no link between surveillance and crime prevention. Even when studies have concluded that “at best” CCTV may help deter petty crime in parking garages, this has only been with exceptionally narrow, well-controlled use, and without the need for facial recognition. And as explored in our previous article, there is overwhelming evidence that rather than improving public safety or security, facial recognition creates a chilling effect on a shocking smorgasbord of human rights.

As in the case of the school in Nice, face recognition cannot be considered necessary and proportionate when there are many other ways to achieve the same aim without violating rights. FRA agrees that general reasons of “crime prevention or public security” are neither legitimate nor legal justifications per se, and so facial recognition must be subject to strict legality criteria.

Human rights exist to help redress the imbalance of power between governments, private entities and citizens. In contrast, the highly intrusive nature of face surveillance opens the door to mass abuses of state power. DPAs and civil society, therefore, must continue to pressure governments and national authorities to stop the illegal deployment and unchecked use of face surveillance in Europe’s public spaces. Governments and DPAs must also take a strong stance to the private sector’s development of face surveillance technologies, demanding and enforcing GDPR and human rights compliance at every step.

Read the rest of the facial recognition and fundamental rights series

-

Facial recognition and fundamental rights 101

This is the first post in a series about the fundamental rights impacts of facial recognition. Private companies and governments worldwide are already experimenting with facial recognition technology. Individuals, lawmakers, developers - and everyone in between - should be aware of the rise of facial recognition, and the risks it poses to rights to privacy, freedom, democracy and non-discrimination.

Read more

-

Your face rings a bell: Three common uses of facial recognition

Not all applications of facial recognition are created equal. In this third installment, we sift through the hype to analyse three increasingly common uses of facial recognition: tagging pictures on Facebook, automated border control gates, and police surveillance.

Read more

-

Stalked by your digital doppelganger?

In this fourth installment of EDRi’s facial recognition and fundamental rights series, we explore what could happen if facial recognition collides with data-hungry business models and 24/7 surveillance.

Read more

-

Dangerous by design: A cautionary tale about facial recognition

In this fifth and final installment of EDRi's facial recognition and fundamental rights series, we consider an experience of harm caused by fundamentally violatory biometric surveillance technology.

Read more

-

Facial Recognition & Biometric Mass Surveillance: Document Pool

Despite evidence that public facial recognition and other forms of biometric mass surveillance infringe on a wide range EU fundamental rights, European authorities and companies are deploying these systems at a rapid rate. This has happened without proper consideration for how such practices invade people's privacy on an enormous scale; amplify existing inequalities; and undermine democracy, freedom and justice.

Read more

Facial Recognition and Fundamental Rights 101 (04.12.2019)

https://edri.org/facial-recognition-and-fundamental-rights-101/

Your face rings a bell: Three common uses of facial recognition (15.01.2020)

https://edri.org/your-face-rings-a-bell-three-common-uses-of-facial-recognition/

Stalked by your digital doppelganger? (29.01.2020)

https://edri.org/stalked-by-your-digital-doppelganger/

In the EU, facial recognition in schools gets an F in data protection (10.12.2019)

https://www.accessnow.org/in-the-eu-facial-recognition-in-schools-gets-an-f-in-data-protection/

Data-Driven Policing: The Hardwiring of Discriminatory Policing Practices across Europe (05.11.2019)

https://www.enar-eu.org/IMG/pdf/data-driven-profiling-web-final.pdf

Facial recognition technology: fundamental rights considerations in the context of law enforcement (27.11.2019)

https://fra.europa.eu/sites/default/files/fra_uploads/fra-2019-facial-recognition-technology-focus-paper.pdf

Serbia: Unlawful facial recognition video surveillance in Belgrade (04.12.2019)

https://edri.org/serbia-unlawful-facial-recognition-video-surveillance-in-belgrade/

At least 10 police forces use face recognition in the EU, AlgorithmWatch reveals (11.12.2019)

https://algorithmwatch.org/en/story/face-recognition-police-europe/

Contribution by Ella Jakubowska, EDRi intern [at time of writing, now Policy and Campaigns Officer], with many ideas gratefully received from or inspired by members of the EDRi network